Oh quickly disappearing photograph

in my more slowly disappearing hand

—Rainer Maria Rilke, “Portrait of My Father as a Young Man” (translated by Stephen Mitchell)

Among the clutter in our attic, unpacked through the twenty years since we moved into this house, rests a large framed photograph of my father taken when he was twenty-nine, or so I’ve been told. That photograph, about twenty-four by eighteen inches, leans against a beam, shrouded in black plastic and sealed with strips of masking tape. It was wrapped that way long before it went into our attic. I don’t remember who had it before me, most likely my late sisters. And I can’t recall the last time the photograph hung on a wall, perhaps before I left for college decades ago.

Yet, despite my not actually having seen the picture for so many years, I remember it clearly. It’s more fixed in my memory than my father himself. He died suddenly a month before my eighth birthday. I was in bed early one morning, not yet up for school. He was in the bathroom shaving; then a loud thud and a clatter. Screams of my mother and sisters, men of the local ambulance squad thumping up the stairs. No chance of resuscitation. Probably an aneurysm of his heart or brain. My mother didn’t want an autopsy. The last I saw of him was a shape strapped onto a stretcher.

My recollections of our interactions are slight, mainly the products of what others told me we did together—movies like Lassie, wooden bleachers to watch our town’s semi-pro baseball team, nickels for ice cream at the diner next to the shop where he repaired and custom made shoes. (I still can visualize the four-inch lift he made for a man with one leg significantly shorter than the other.) The only event I really recall is a time when I was six. My friend H.D. and I were so pleased with ourselves for sticking pins through the outer skin layers of our fingers. We ran into his shop to show him. He feigned being impressed and opened the cash register for a reward of ice cream money.

When he died, he was sixty-two. In January 1944, the month of his death, he had achieved the average lifespan for an American male at that time. I, his surviving child, have enjoyed many more years, even beyond today’s average, thanks to diet, exercise, and modern medicine. Had he survived and lived on, he would be one hundred and thirty-six now.

He was in his mid fifties when I was conceived, my brother and sisters already grown. I’ve had this imagined conversation for quite a while, my father moving close to my mother in their bed and whispering, “What could happen at our age?” Little did he know. The joke was on them. Although a pregnant woman in her forties today would barely get a second glance, it was a rarity back then, a bit embarrassing even though my parents had been long married. Probably the notion of people so old doing it. Their ages made me feel different, odd, people assuming my parents were my grandparents.

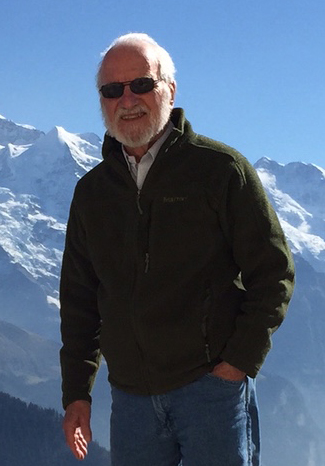

My sense of my father in his final years comes from two black and white snapshots, one in which he stands in our yard in a white shirt and dark tie, hands at his side, looking straight ahead, suggesting a tension at being photographed. He wore rimless glasses, was bald expect for a thin fringe back from his temples, a small man, trim. The other snapshot was taken during a parade, my father in a row of men, an air raid warden’s insignia wrapped around his upper arm. He was, I’ve been told, very proud of his role in World War II, at a time my brother was an army first lieutenant in Europe. I played with metal toy soldiers, demolishing Nazis with comic book exclamations.

But in the attic photograph, my father was still not yet thirty, probably with a newborn son, my brother. The photograph, tinted with color, seems meant to function as a portrait, my father posed in a three-quarter profile, his expression serious, though not grim. What stands out most for me is the full head of thick wavy hair, impressively coiffed. At twenty-nine I had a bald spot at the crown of my head, an earlier start than his; but eventually he was much balder than I’ve ever been, though I’m clearly a bald man.

How could I have really known my father? He was gone before I reached an age when serious conversations would have revealed his thoughts and experiences to me firsthand. But for most of my life, while they were still alive, my siblings told me how much he and I were alike in quirks and disposition. Nature over nurture.

I lack enough sense of his disposition to make a judgment. Perhaps his amusement at the pins through my fingertips is a clue. I tend to regard the world with an ironic shake of my head. Did he? I do know he was an obsessive reader. In one oft-told tale he was supposed to be minding my then-young siblings one evening while my mother was with friends. She came home long after their bedtimes, finding house lights ablaze, kids still playing, my father engrossed in a book. Sounds normal to me.

Beyond the tendency to live in our heads through books, he and I share political and travel inclinations, along with an aversion to military service. As a young man in Eastern Europe, when borders were so fluid it’s hard to identify the then country of his origin, he fled to escape conscription, an act I associate more with a press gang than a letter from the draft board. I didn’t leave my country but took the easy way out through six months active duty in the National Guard, never advancing beyond private E-2. On the other hand, my brother, his first son, left active duty as a Captain, retired from the reserves as a Lt. Colonel, so committed to the military he was buried in Arlington Cemetery wearing his officer’s uniform.

My brother’s politics were fixated on the super-patriotic right. Like my father, I lean left, proud that my heritage involves a man who spent part of his twenties as an organizer for Eugene V. Debs. Supposedly in the 1930s, he and my brother got into frequent shouting matches over political issues, several of which I must have overheard while in my crib.

Yet my father and brother shared manual dexterity and fine motor control that I sadly lack, even though my left-handedness comes from my father. He could design and execute those special shoes. My brother became a podiatrist and performed surgical manipulations on people’s feet. I wince when taking out a splinter and, if given the opportunity, probably would have mutilated a shoe or a foot.

My father, I was told, could function in a dozen languages, perhaps because of his travels through various countries to reach American. I get by in English. He was, I have no doubt, highly intelligent, my mother no slouch herself, producing a son and daughter who were high school class valedictorians and another daughter who was salutatorian. I, his second and last son, blundered my indifferent way into graduating with low honors.

But what could his intelligence have done for my father in the first half of the twentieth century when opportunities for smart people were so limited? I think of him in a category with the fathers of many of my college friends, men no doubt as bright or brighter than their offspring, who worked with their hands or ran small shops because there was nothing else for them to do, certainly not the executive positions or professional roles that their sons—and occasional daughters—filled.

Perhaps my father was content to be self-employed and ease the walking of those with malformed feet, and then come home to read more books and lose himself in political musings.

The portrait photograph seems inappropriate for such a man, the self-important flaunting it suggests. Its existence always puzzled me from the time I was able to wonder. It couldn’t have been cheap considering the size and the frame, and our family never had money for frivolities. Was it my father’s idea? That doesn’t seem like him, such a seeming display of vanity. Was it a gift? If so, from whom?

And why wasn’t there a similar picture of my mother, equally large and equally framed? His must have been taken around 1910, a time when family photographs were coming into vogue. In them, the husband-father sat pompously in a chair, while the wife and children stood behind. I can’t see my father sitting for such a pose or not being embarrassed to see his face hanging on a wall.

Now, of course, the picture doesn’t hang, hasn’t hung for years. It’s up in the clutter of our attic amidst suitcases, a clothes rack, boxed documents, unused comforters, rolls of wrapping paper, bows. And it’s unlikely that I’ll ever unwrap it again.

As we contemplate downsizing, preparing for the time we won’t need a multiroom house or have the energy to care for it, I wonder what will become of that picture. We’d already donated a few hundred CDs now that we have access to endless online music. We will donate our books, the hundreds I’ll never have time to read again. Someone, somewhere still cares about all those authors.

But my father’s picture? Other than me, there is not another living human being who ever knew him, who would get a frisson of recognition from looking at his face. Even I possess only the vaguest sense of his hand touching mine as he placed a coin for ice cream.

I wish he had lived long enough for me to learn about him—the books he read, his youthful travels, his ideas about the world. I have no doubt he would have interested me a great deal, and I’m pretty sure I would have taken great pleasure in our time together.

Once I’m gone, which will be sooner rather than later, my father will become one more totally forgotten being, one of the millions who once existed since the first homo sapiens. His name probably exists in some census documents, evidence that there was once such a man. But to what end? The few remaining images of him will be meaningless to anyone who happened to see the man depicted.

But, aside from official facts and figures , no one will know his real history—what he did, where he went, what he read, what he thought, what he felt. People from the past we do remember—a tiny fraction of all who ever walked the earth—did something significant or infamous. A few have written memoirs that still matter. If my father had, the interesting bits would have accumulated before he sat for that picture—the escape from a brutal army, travels though Europe, romance with my mother, recruiting for Debs. Post picture, for all those years as a husband and father, his life sounds routinely mundane, though I hope it gave him satisfaction.

Better to leave the picture portrait wrapped in black plastic. Opening it wouldn’t release the person. I’d certainly learn nothing new to add to the little about him I do know. Abandoned in an attic, removed from the world, sealed into darkness—the way of all our destinies.

##