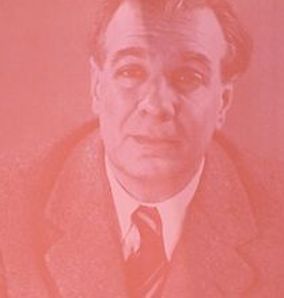

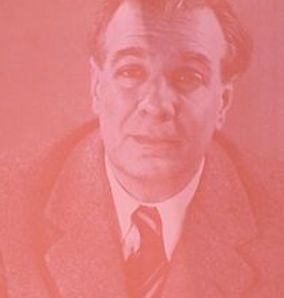

JORGE FRANCISCO ISIDORO LUIS BORGES

JORGE FRANCISCO ISIDORO LUIS BORGES

Born: August 24, 1899

Died: June 14, 1986

A little known fact:

Jorge Luis Borges supported the purging of Peronists from the government and the dismantlement of the former President’s welfare state after the overthrow of President Perón in 1955. He sharply criticized the Communists for opposing these measures in lectures and in print—and this opposition to the Party led to the loss of his longtime love interest, Argentine Communist Estela Canto.

A much better known fact:

Juan Perón began transforming Argentina and ideological critics were dismissed from government positions in 1946. Authorities informed Borges that he was being “promoted” from his position at the Miguel Cané Library to inspector of poultry and rabbits at the municipal market, explaining, “Well, you were on the side of the Allies, what do you expect?” Borges resigned from his government post the following day.

Jorge Luis Borges’s most well-known books, Fictions (1944) and The Aleph (1949) are connected short story collections with multiple themes, ranging from dreams, labyrinths, fictional writers, philosophy, religion, God and infinity. He also contributed to philosophical literature, the fantasy genre, magical realism genre, poetry, and was a prolific essayist. On Writing is a recent collection of his best essays, reviews, articles, prologues, and capsule biographies.

The Borges family educated Jorge at home in Buenos Aires until the age of eleven in a bilingual environment in Spanish and English. His father gave up practicing law due to failing eyesight, and in 1914, moved to Geneva, Switzerland for treatment. Jorge earned his baccalauréat from the Collège de Genève in 1918 and the family lived the next three years in Lugano, Barcelona, Majorca, Seville, and Madrid.

Borges began his literary career in 1921 when he collaborated with fellow poets on “Ultra Manifesto” in which they advocated a new poetic movement in Spain—the avant-garde, anti-Modernist Ultraist literary movement.

On returning to Argentina in 1921, Borges published his poems and essays in surrealist literary journals. From 1924 to 1933 he was very prolific and he founded several literary magazines. The editor of On Writing believes that the earliest reflection of his mode of story telling (ultimately labeled “magical realism”) was in his explanation of the interweaving of the marvelous with the everyday in “Stories from Turkestan” written in 1926.

At that time, he also began several important friendships with women: Norah Lange, Victoria Ocampo, and Elsa Astete. Norah Lange was the darling of the Buenos Aires avant-garde; her home became the center of weekend literary salon. Borges was fond of Norah, but she took an interest in a literary rival of his and broke his heart for a time. Victoria Ocampo, was a writer, editor, and translator who promoted Borges’s writing through Sur, a literary magazine she founded in 1930. Elsa Astete was a 20-year old whom Borges met in 1928 and she engaged in a brief romance with Borges before suddenly marrying another man. Forty years later, however, Elsa Astete Millán became Borges’s first wife.

Borges was unable to support himself as a writer when his own vision began to fail in his early thirties. So, he began a career as a public lecturer and put political essays behind him for a while. His writing took new directions both in topics and his fundamental style. He published another collection of essays, Discusión, in 1932 about a more recent, non-literary passion–the magical realm of cinema.

His first short story was “Streetcorner Man,” inspired by the death of a compadrito and rendered with descriptive, gritty realism with a twist at the end. He published it under the pseudonym of “Francisco Bustos,”one of his ancestors, and the story was a tremendous success—much to his surprise and puzzlement for years afterward.

In 1933 Borges began a series of sketches published together in 1935 as A Universal History of Infamy, taking characters and concepts from other published works and “re-inventing” them. He blended fact and fiction, created mythical resonance, and created in many of the stories a surrealistic authenticity. Years later Latin American “magical realists” would cite Borges as the central inspiration for their work. However, in 1935 he was really only beginning the heart of his career when he wrote the prototype “Borgesian” story, “The Approach to al-Mu’tasim,” a review of a fictional novel. Today, literary critics such as Harold Bloom often characterize stories as either Chekovian or Borgesian. And Borges would explain the difference in terms of their views of causality.

Borges’ ailing father became completely dependent on his mother and Borges needed to find a source of steady income. So, in 1937 he found the position already alluded to as First Assistant in the Miguel Cané Branch of the Municipal Library, classifying and cataloging the library’s holdings—included some of his own work. In 1938 he had a minor accident, sustaining a wound that ultimately became infected; he became ill and hallucinated for a week. Then, after an operation in the hospital, he developed septicemia and slipped between life and death for a month.

After those episodes, Borges’s stories increasingly mixed philosophy, fact, fantasy and mystery and he began to write political articles again—not supporting a single political system. He criticized broad trends of the age: Anti-Semitism, Nazism, and fascism—and that caused him serious concerns when fascists came to power in the forties.

Being fired from his library post in 1946 proved to be a blessing because that situation forced him to find a position as a lecturer on American and English literature, traveling across Argentina and Uruguay. He was paid much better and he adapted well to the new life style well—though he could not conceal his disappointment in the direction taken by his country.

Then in 1955 he was appointed to serve as director of the National Public Library. His stoicism was as resonant as his stories: “I speak of God’s splendid irony in granting me at one time 800,000 books and darkness.” He was determined to make the library into a cultural center, starting a program of lectures and resurrecting the library’s journal. The following year he was appointed to the professorship of English and American Literature at the University of Buenos Aires.

He was completely blind by his late fifties and he never learned braille. Scholars have suggested that as a result of his progressive blindness, he was prompted to create innovative literary symbols through his imagination.

In 1961 Borges earned international stature when he received the Prix International that he had to share with Samuel Beckett that year. His international standing was greatly strengthened later in the 1960s because his works became available in English and because of the Latin American Boom in literature that attended the success of One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez.

Borges was a political conservative who dismissed Marxism and who also rejected the politics of cultural identity that was popular in Latin America for some time. As a universalist interested in world literature, he found himself totally out of step with Peronist Populist nationalism.

When Borges traveled internationally, his personal assistant, María Kodama, a former student, often accompanied him. In April 1986, a few months before he died of liver cancer in Geneva, he married her via an attorney in Paraguay—a common practice of Argentines circumventing the Argentine laws regarding divorce. As his widow and heir, she gained control over his work and her administration of his estate resulted in commissioning of new translations by Andrew Hurley that have become the standard translations in English.

The philosophical term “Borgesian Conundrum” is the ontological question of “whether the writer writes the story, or it writes him.” Borges, in “Kafka and His Precursors,” posed this when he wrote about works written before Kafka’s:

“In the critics’ vocabulary, the word ‘precursor’ is indispensable, but it should be cleansed of all connotation of polemics or rivalry. The fact is that every writer creates his own precursors. His work modifies our conception of the past, as it will modify the future.”

Looking back, the critic Ángel Flores, “the first to use the term magical realism” for literature in 1955 (art critic Franz Roh used the phrase in 1925), calls the beginning of the movement the release of Borges’s A Universal History of Infamy in 1935. It is likely that Flores means the magical realism movement in Latin America since Kafka is central to the formulation of the Borgesian Conundrum and is referenced explicitly by several of the five leading novelists in the Latin American Boom while acknowledging their debt to Borges.

A FEW OF BORGES’S QUOTES

“If I were asked to name the chief event in my life, I should say my father’s library.”

“To be in love is to create a religion whose god is fallible.”

“Not granting me the Nobel Prize has become a Scandinavian tradition.”

BORGES’ NOTABLE WORK

Fictions (1944), The Aleph (1949), Labyrinths (1962); Movies: Invasión (1969), The Spider’s Stratagem (1970), The Others (1974)

BORGES’ AWARDS

Prix International (1961)

Jerusalem Prize (1971)

Edgar Allan Poe Award (Mystery Writers of America, 1976)

Balzan Prize (Philology, Linguistics and literary Criticism, 1980)

Prix Mondial Cino Del Duca (1980)

Miguel de Cervantes Prize (1980)

Legion of Honor (France, 1983)

SOURCES

Jorge Luis Borges. The Aleph and Other Stories 1933-1969. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1970.

Andrew Hurley (trans). Jorge Luis Borges: Collected Fictions.

Suzanne Jill Levine (ed.) Jorge Luis Borges: On Writing. New York: Penguin Books, 2010.

Edwin Williamson. Borges: A Life. New York: Viking, 2004.

http://www.themodernword.com/borges/borges_biography.html

Richard Perkins is a recent graduate of the Johns Hopkins University MA in Writing Program. He is working on an historical novel and is revising a collection of connected stories and a novella.