Have you ever worked on a story that you knew was tied into another story: one you didn’t want to write. One you have never wanted to write.

And then you wrote it.

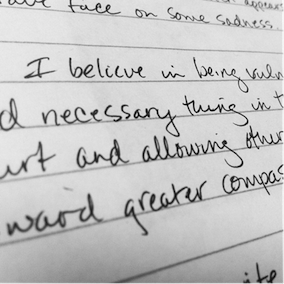

Ultimately, it was the most vulnerable writing you’ve ever done.

The reward: Intuitive knowledge. Vulnerability. Writing that came from your body. Connecting seemingly disparate events.

Then you gave your story to an editor to line edit, only to have her do developmental editing, pulling your weaved stories apart. You clearly didn’t get what you asked for or thought you were going to get. Then you read comments, “I so love what you’ve done so far…your voice is wonderful. The images are strong; the emotions (realism) are powerful. I recommend starting here and going forward.” Maybe it’s not so strange that this scenario happened to me while writing this column. We’ve all been there.

Think about the last work-shopping group you were in or the last time a friend read your latest chapter or essay. We know we have to connect with ourselves when we write, but then we also have to learn to not take responses to our writing as personal. It’s most important to stay true to self, have your voice appear on every page, and continue to learn the craft and cultivate our writing skills, all while staying connected to our body.

Intellectually I know to feel is to be vulnerable.[i] Being vulnerable is a necessary part of opening to love and passion.[ii] And being vulnerable is, paradoxically, a type of strength. To be a good writer, to write what needed to be written, to tell the story I wanted to tell, I couldn’t escape vulnerability.

Owning our story can be hard but not nearly as difficult as spending our lives running from it. Embracing our vulnerabilities is risky but not nearly as dangerous as giving up on love and belonging and joy—the experiences that make us the most vulnerable. Only when we are brave enough to explore the darkness will we discover the infinite power of our light. ― Brené Brown

Brene Brown defines vulnerability as uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure. To make real connection we have to be willing to open up. We have to allow ourselves to be seen. This is also true in our writing. Our writing can’t escape vulnerability if we commit to it on the page. The more we work on our connection with our bodies, the more vulnerable we can be in our writing. This is true both ways.

Perhaps learning the body, the science of it, the mechanics, is akin to the psychological quest to hold the dark places open, look into them, deprive them of their power. If I understand the ways in which a body can fail, will the dark places lose their fearfulness? Or, if I understand all the ways bodies fail, the myriad of ways in which we are frail and given to mechanical meltdown, facing my own physical breakdown won’t feel so lonely. So terrifyingly alone”[iii] (Zwartjes, p. 25).

The thing about vulnerability is that we often aren’t self-aware enough to navigate vulnerability, even if we are self-aware enough to know that we’re vulnerable. We can develop self-awareness by committing to a practice of mindful writing exercises that help us connect with our body and its vulnerabilities.

Exercise 1: Find a quiet place, lie flat or sit cross-legged and close your eyes. Scan your body. Locate points of tension. Consider why they are tight, then describe via writing.

Initially when I was writing my story I was tense, totally guarded. I noticed my shoulders were up by my ears. Turning my head from side to side alleviated the tightness in my neck. I found the courage to open up after setting intention to tell truths, especially the uncomfortable ones. It was a risk. It was awkward. I was scared. Somehow I was able to write through the tension.

Exercise 2: Describe a time when you felt guarded in a social situation. What did your body do? Where was it tense? Describe a time when you were open to a new idea, different perspective. How did your body receive this openness?

Exercise 3: Write about a time you dropped the invisible armor that shielded your heart and let the love of others penetrate you. Describe a time when your body felt fully relaxed. What physical sensations were you aware of? What/who was surrounding you?

There can be no vulnerability without risk;

There can be no community without vulnerability;

There can be no peace, and ultimately

No life, without community. – M. Scott Peck

We can reflect on our experiences and explore more deeply our physical body and vulnerabilities in our writing.

When we were children, we used to think that when we were grown up we would no longer be vulnerable. But to grow up is to accept vulnerability. To be alive is to be vulnerable.

Madeleine L’Engle

How does vulnerability feel? For me, it is uncomfortable and uncertain. Vulnerability was where courage and fear met in my weaved stories.

Only you can write your stories. Be patient and kind with yourself.

The strongest love is the love that can demonstrate its fragility -Paulo Coelho

Exercise 4: Write about your softer, more receptive side.

Exercise 5: Describe a time you took an emotional risk or felt emotionally exposed. Write about a time you were willing to place your private and innermost workings in another’s hands. (For example, a time of sexual desire, self-disclosure, standing up for yourself). Write about the vulnerability of your flesh (initiating sex, exercising in public). Write about how you are worthy of connection to your body.

Vulnerability is based on mutuality and requires boundaries and trust. Vulnerability is another way of saying; “I trust you and I feel safe with you.”[iv] Writing with an ongoing connection between our body and ourselves is something that we can nurture and grow. Trusting your body is about trusting yourself. Writers trust their audience. For a reader to place trust in your hands is humbling.

We cultivate love when we allow our most vulnerable and powerful selves to be deeply seen and known, and when we honor the spiritual connection that grows from that offering with trust, respect, kindness and affection.

Exercise 6: What are you most afraid of when you write? Write for ten minutes after reading this quote from Brene Brown: “The one thing that keeps us out of connection is our fear that we’re not worthy of love and belonging.”

Sometimes it’s awkward to write openly about certain issues, but if we do it could ultimately be rewarding. Love, imagination, and creativity are intimately connected.

What makes you vulnerable makes you beautiful. ― Brené Brown

Find that beauty in you.

Final exercise: What is the one thing you would never write about?

Now write it.

[i] Brown, Brene. (2012). Daring Greatly: How the Courage to be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent and Lead. New York, New York: Penguin Group.

[ii] Groover, R. J. (2011). Powerful and Feminine: How to Increase Your Magnetic Presence & Attract the Attention You Want. Deep Pacific Press. p. 171.

[iii] Zwartjes, A. (2012). Detailing Trauma. A Poetic Anatomy. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

[iv] Groover, R. J. (2011). Powerful and Feminine: How to Increase Your Magnetic Presence & Attract the Attention You Want. Deep Pacific Press. p. 175

Debbie spent 30 years as a registered nurse. She became a certified applied poetry facilitator and journal-writing instructor in 2007. She is currently a student in the Johns Hopkins Science-Medical Writing program. Her publications have appeared in Journal of Poetry Therapy, Studies in Writing: Research on Writing Approaches in Mental Health, Women on Poetry: Tips on Writing, Teaching and Publishing by Successful Women, Statement CLAS Journal, The Journal of the Colorado Language Arts Society, and Red Earth Review.

The female nether regions divide Americans into two distinct camps. On one side are the people who cannot bring themselves to say, hear, or read the word vagina no matter how legitimate the circumstances that prompt its use. Depending on whether they over-identify with daytime talk show hosts or public leaders, the anti-vagina crowd either reverts to baby talk (e.g., vajayjay) or condemns the dictionary-approved terminology as profanity and debauchery most vile. Sexual repression being the obvious diagnosis, I can do nothing but feel sorry for the stricken and wield the word with purpose and clarity whenever warranted.

The female nether regions divide Americans into two distinct camps. On one side are the people who cannot bring themselves to say, hear, or read the word vagina no matter how legitimate the circumstances that prompt its use. Depending on whether they over-identify with daytime talk show hosts or public leaders, the anti-vagina crowd either reverts to baby talk (e.g., vajayjay) or condemns the dictionary-approved terminology as profanity and debauchery most vile. Sexual repression being the obvious diagnosis, I can do nothing but feel sorry for the stricken and wield the word with purpose and clarity whenever warranted.