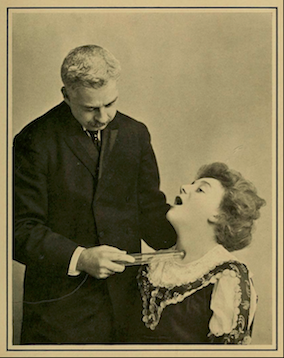

A narrative based in the bodily experiences—physical, emotional and more—of a central subject (personal essay or poetry) or character (fiction). Body narrative is a growing trend in not only artistic venues but also medicinal. “Developed at Columbia University in 2000, ‘Narrative Medicine’ fortifies clinical practice with the ability to recognize, absorb, interpret, and be moved by stories of illness. We realize that the care of the sick unfolds in stories, and we recognize that the central event of health care is for a patient to give an account of self and a clinician to skillfully receive it.” (Columbia University Program of Narrative Medicine)

Narrative

A story, whether fictional or true and in prose or verse, related by a narrator or narrators (rather than acted out onstage, as in drama). A frame narrative is a narrative that recounts the telling of another narrative or story that thus ‘frames’ the inner or framed narrative. An example is Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,’ in which an anonymous third-person narrator recounts how an old sailor comes to tell a young wedding guest the story of his adventures at sea. (Norton).

Narrative Lengths

Novel — Over 70,000 words

Novella — 17,500 to 70,000 words

Novelette — 7,500 to 17,500 words

Short Story — 1,000 to 7,500 words

Short Short Story — Under 1,000 words

Microfiction — Generally, 500 words or less (Some editors will consider everything 1,000 words or less to be a short short story or flash fiction. Some editors will consider a microfiction to be 100 words or less. There is a great deal of variance between editors. If in doubt, simply ask the particular editor.)

Narrative Forms

Novel: a long work of fiction, typically published (or at least publishable) as a standalone book; though most novels are written in prose, those written as poetry are called verse novels. A novel (as opposed to a short story) conventionally has a complex plot and, often, at least one subplot, as well as a fully realized setting and a relatively large number of characters. One important novelistic subgenre is the epistolary novel—a novel composed entirely of letters written by its characters. Another is the bildungsroman.novellaa work of prose fiction that falls somewhere in between a short story and a novel in terms of length, scope, and complexity.

Novella: it can be, and has been, published either as a book in its own right or as part of a book that includes other works. Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis is an example.

[Novelette: Shorter than a novella, longer than a short story.]

Short Story: a relatively short work of prose fiction that, according to Edgar Allan Poe, can be read in a single sitting of two hours or less and works to create “a single effect.” Two types of short story are the initiation story and the short short story. (Also sometimes called microfiction, a short short story is, as its name suggests, a short story that is especially brief; examples include Linda Brewer’s “20/20” and Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl.”)

[Short Short Story: a short story that is approximately 1,000 words or less. Often, expositional attributes are cut or shortened.]

[Microfiction: a short story that is approximately less than 500 words. Often expositional attributes are cut or shortened. Time lapses will be briefer and the reader will be asked to invest far more imaginative response. Micro fictions are often close to poetry and can sometimes be interchangeable with prose poetry.]

Body Narrative Writing Exercise

Think of a time when you were most ill. This illness could be bodily, emotional or both. Write a personal essay in first person pov about the experiences of this illness. This account might be realism or even surrealism, such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s autobiographical short story, “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

Submit Your Work for Individualized Feedback

Please use Universal Manuscript Guidelines when submitting: .doc or .docx, double spacing, 10-12 pt font, Times New Roman, 1 inch margins, first page header with contact information, section breaks “***” or “#.”

Sources

The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present. Eric Kandel.

A Handbook to Literature

“Cogito et Histoire de la Folie.” Jacques Derrida.

Cognitive Neuropsychology Section, Laboratory of Brain and Cognition.

Eats Shoots and Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation

The Elements of Style.

New Oxford American Dictionary

The Norton Anthology of World Literature

The Norton Introduction to Philosophy

Woe is I: The Grammarphobe’s Guide to Better English in Plain English

Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft

Writing the Other