I was not ladylike, nor was I manly. I was something else altogether. There were so many different ways to be beautiful.

—Michael Cunningham (A Home at the End of the World)

Traditional conceptions of gender and sexuality permeate every aspect of our society and culture, affecting not only how we see the world around us, but also how we use language to communicate ideas and information. As a result, contemporary writers are often the subject of gender stereotyping, with male and female writers being associated with radically different styles. This sense that one must “perform” a gender role in order to be taken seriously causes many writers to conceal their authentic selves and passions because they fear the judgment of readers and other writers.

Yet, as Edward Abbey once famously wrote, “It is the difference between men and women, not the sameness, that creates the tension and the delight.” With this in mind, many writers today are increasingly shedding the outdated dogmas of gender and investigating their own definitions of masculinity, femininity, and the areas in between and beyond. These writers are using their poetry and prose to address cultural and social biases directly, and to help others navigate the uncharted areas of modern gender and sexuality.

A Brief Guide to Crossing the Gender Divide

Crossing the so-called gender divide is no easy feat. Womanhood, sexual orientation, and “accepted” behavior, are steeped in literature and social discourse. It can be difficult for writers to see through the haze. The advice below for writing against gender norms will help author avoid common pitfalls and create innovative works that deconstruct the dichotomies of gender and sexuality.

- Avoid gendered language.

For many of us, traditional gender roles have been reinforced since childhood. As early as elementary school, we were taught to use masculine nouns and pronouns (he, him, his) when a subject’s gender was unclear or when referring to members of both sexes. This is often referred to as using the “universal he.” At the same time, female nouns and pronouns (her, she, hers) were often used to describe objects, animals, and forces of nature. This gendered language reflects and reinforces outmoded associations for both sexes, placing men in dominant roles and women in subservient ones.

By using non-gendered or gender-neutral terms, writers can create content that is accessible to both male and female readers. Examples included changing stewardess to flight attendant, freshman to first-year student, fireman to firefighter, mankind to human beings, and so on. In addition, special attention should be given when writing about sexual orientation. American transgender activist and author of the award-winning novel Stone Butch Blues, Leslie Feinberg, writes about the difficulties of lesbian and transgender life, and cautions writers about confusing sex with gender when referring to a character or the self.

By moving the emphasis away from normalized undertones of gender, sexuality, or sexual attraction, writers invite new readers and further self-reflection and imagination.

- Try out new styles and aesthetics.

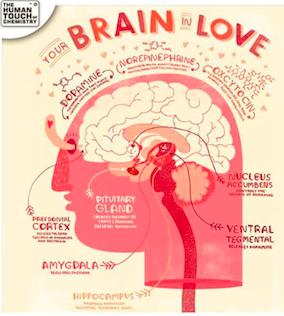

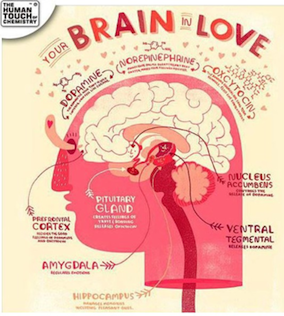

It’s been proven that linguistic styles differ between males and females. Women’s speech tends to be more emotionally expressive and employs more compliments and apologies. As Australian researcher Janet Holmes suggests, “Females are more attentive to the affective function of conversation and more prone to use linguistic devices that solidify relationships” (Holmes, 1993). Likewise, Leigh Ann Jasheway (2010)—humor author and columnist, writing and life coach, and part-time instructor at the University of Oregon—says women are more likely to start a sentence with a question, state preferences in their writing rather than make demands, and use apologetic language even when being decisive.

This means that while men prefer to write about an accomplishment—a battle won, a dog trained, a disease conquered—women often favor a focus on the relationships and emotional relevance of a story, such as what happens to the family left at home while the spouse is off fighting the war; what it’s like for the dog to learn to sit and stay; or how to handle the strain of caring for an ailing family member.

According to the researcher Evelyn Fox Keller (1978), objectivity and rationality are highly masculine qualities, making male writing in many cases more similar to a scientific investigation than the interior journey of women’s writing. Men also tend to use more commanding and aggressive language. Jasheway (2010) says this may explain why women are more likely to read literary fiction and self-help books, while men tend to favor history, science fiction, and political tomes.

These writing qualities, while not universal, represent how modern readers typically approach and make assumptions about a text. Rather than judge a book by its cover, readers will judge it by its author’s gender—among a host of other qualities—and respond to the text accordingly. Take for example, J.K. Rowling. She used her initials “J.K.,” because she was afraid that boys wouldn’t read her if they knew the book was authored by a woman. Other examples include: Armandine Lucile Aurore Dupin wrote novels in the 1800’s under the pseudonym George Sand and Alice Bradley Sheldon, who wrote science fiction using the pen name James Tiptree. By incorporating styles and aesthetics linked to both genders, writers can create more original and imaginative texts, which will better engage and inspire readers to overcome stereotype definitions and gender norms.

- Use characters to examine gender identity.

Speaking about women’s writing, Helene Cixous, the author of “The Laugh of the Medusa,” says the following:

[W]omen must write her self: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies—for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal. Women must put herself into the text—as into the world and into history—by her own movement . . . I wished that that woman would write and proclaim this unique empire so that other women, other unacknowledged sovereigns, might exclaim: I, too, overflow; my desires have invented new desires, my body knows unheard-of songs. (p. 875-876)

Cixous suggests that it is vital now, more than ever, for writers to create characters and literary voices that defy gender-based or sexual classification. Instead of painting males as dashing heroes and bloodthirsty warlords, or women as damsels in distress and emotional wrecks, writers should strive to build rounded characters that tangle with and overcome gender stereotypes. The gender of Jeanette Winterson’s narrator in Written on the Body, a romance story that examines the relationship between sex, gender, sexuality and narrative, is ambiguous. In doing so, the author challenges the notion of gender and sexuality as the foundation of identity.

A great contemporary example is New York Times bestseller and author of the Plum Series, Janet Evanovich, who does an exceptional job of finding the balance between masculine and feminine in her own writing. Her series’ protagonist, Stephanie Plum, is a bail bondswoman who performs her job with a characteristically feminine style in a male-dominated industry. Similarly, J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series was successful not only because of its suspenseful plots and high-quality writing, but also because the characters transcend stereotypes of gender and age. This is why girls, boys, men, and women alike continue to devour her books by the millions every year.

In a recent interview, Evanovich suggested her method for developing rounded, multidimensional male and female characters was to incorporate traditional masculine elements into female characters, and vice versa. This is a simple and useful method for all writers, leading to more exciting, unique characters that provoke further thought on issues of gender and sexuality.

Conclusion

By employing everything from pronouns to syntax to gender-bending protagonists, writers have the power to take a meaningful stance on what gender and sexuality mean today and in the future. Rather than suppressing our everyday struggles with masculinity, femininity, sexuality, and gender roles, we should use them to strengthen our resolve, and to show readers with similar struggles that they are not alone.

Writing Prompts:

Describe a time you were conflicted about the use of “girl” versus “woman” or “boy” versus “man” in your writing.

Write about your experience with masculine or feminine dominant language.

In what ways do the language, chapter titles, and references used show gender bias?

What are some of your favorite examples of intriguing male and female characters?

Explain how integrating style differences can make your work more inclusive of different genders and gender expressions.

Write a paragraph from the perspective of another gender. When finished, write another paragraph from the perspective of someone from the opposite gender. Are there any differences?

Cixous, H. (1976). The laugh of the medusa. (K. Cohen & P. Cohen, trans.). Signs 1:4, 875-893. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Halmstad, H. (n.d.). Gender, Sexuality and Textuality in Jeanette Winterson’s

Written on the Body. Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:526130/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Holmes, J. (1993). Women’s talk: The question of sociolinguistic universals. Australian Journal of Communication, 20:3. 125-148.

Jasheway, L. A. (September 3, 2010). How to write intriguing male and female

characters. Writer’s Digest. Retrieved December 11, 2014 from http://www.writersdigest.com/writing-articles/by-writing-goal/improve-my- writing/he-said-she-said

Keller, E. F. (September 1978). Gender and science. Psychoanalysis and Contemporary Thought, 409-433.

Debbie spent 30 years as a registered nurse. She became a certified applied poetry facilitator and journal-writing instructor in 2007. She is currently a student in the Johns Hopkins Science-Medical Writing program. Her publications have appeared in Journal of Poetry Therapy, Studies in Writing: Research on Writing Approaches in Mental Health, Women on Poetry: Tips on Writing, Teaching and Publishing by Successful Women, Statement CLAS Journal, The Journal of the Colorado Language Arts Society, and Red Earth Review.