Jeremy Freedman, an artist whose works are exhibited in the Eckleburg Gallery, discusses his artistry with Eckleburg and why he prefers making pictures to painting. Click here to view his art.

I am not interested in making photographs as much as I am in making pictures. Sometimes photographs have too much “reality” for my taste. And of course, it’s not really reality, but only a kind of photographic reality, one that may constrict experience and not open the eye or the mind. I’m interested in a different kind of focus, one that lets the mind wander inward a little bit, in pursuit of the ambiguity of life and the slipperiness of truth. My various techniques are ways to isolate and concentrate on the experience of seeing. And for me, my pictures are as abstract as words, a chance meeting of my memories and the present moment.

Eckleburg: What is “The Illusion of Validity?” Why an illusion? Are we not valid?

JF: We’re valid but our thoughts and perceptions may not be. The title of this body of work, “The Illusion of Validity,” comes from the book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” by psychologist Daniel Kahneman. In that extraordinary work, which explains a lot about how our minds work and why we may often make wrong choices, Kahneman says, “Narrative fallacies arise inevitably from our continuous attempt to make sense of the world.” I would go farther than most psychologists and question whether there is ever any basis for the belief that we can understand the world objectively. We’re all prisoners of our subjectivity. Anyway, it’s useful to challenge ourselves.

Eckleburg: Why are you interested in different kinds of focus? Is truth really slippery? Is truth or reality too starkly bright? Or, what is it about reality that makes you want to make it go out of focus?

JF: What we perceive as truth changes according to the differing circumstances of a particular moment. We are always learning and unlearning. My use of focus is a way of reminding me that the surface “reality” of many photographs is an illusion too.

Eckleburg: Are your works always in presented in black and white? Is this part of what you’re trying to convey with the “Illusion of Validity?”

JF:Black and white is a useful distancing mechanism, but I also often photograph in color. See my website, jfreenyc.com, for more pictures.

Eckleburg: Among the pieces exhibited in The Eckleburg Gallery, which one is your favorite?

JF:It is not possible to choose a favorite, but “Pessoa in New York” is important to me because, even though I admire his writing highly, the life story of Fernando Pessoa has assumed metaphorical significance for me. Pessoa’s ability to create and fully inhabit dozens of different heteronyms illustrates, to me, fundamental mysteries of our consciousness. The photograph comes from a short film I made some years ago about an imaginary trip by Pessoa to New York City. You can see it here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ou-2gKetRgg

Eckleburg: Why do you choose the medium of photography to express your artistic creation?

JF: It’s faster than painting!

Jeremy Freedman is an artist and writer in New York City. His photographs have been exhibited in Europe and the United States and were recently featured in the Monarch Review and Urbanautica. His work is on the web at jfreenyc.com.

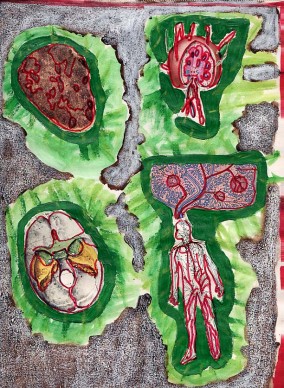

Ira Joel Haber

Ira Joel Haber