In the essay below, Kim Buck, whose drawings are exhibited in the Eckleburg Gallery, likens her drawings to the unceasing efforts of Sisyphus.

In the essay below, Kim Buck, whose drawings are exhibited in the Eckleburg Gallery, likens her drawings to the unceasing efforts of Sisyphus.

I draw.

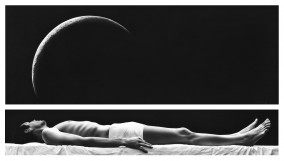

Inspired by a broader theoretical framework informed predominantly by the philosophies of Friedrich Nietzsche and Albert Camus, as well as my own growing understanding of the repetitive nature of my drawing process – my focused and attentive study of the human form, the daily act of placing black charcoal on white paper, and my repeated gravitation towards particular themes – On Sisyphean Certainty is an exploration of human trajectory.

I draw.

How do we human beings continue to stay upright in a world that constantly tests our stability? How do we maintain some sense of equilibrium, as a species and as individuals, within this large and formidable universe? Why do we continue to strive and struggle? Has all of this been before and will be again or is the only one ultimate certainty our mortality?

I draw.

“The eternal hour glass of existence will be turned again and again – and you with it, you dust of dust!” [Nietzsche, F. The Gay Science, translated by Walter Kaufmann, Random House, New York, 1974, p. 341.]

I draw.

Nietzsche contends that the physical structure of the universe is composed of a never-ending, identically recurring circle of time compelling us to repeat our lives over and over, exactly as we have chosen.

I draw.

The consequences of this idea could suggest metaphors to live by: to positively affirm our lives such that we would want to relive every facet in precisely the same way again and again; to derive, not a sense of pessimism from this wisdom, but find pleasure in repetition; to recognize that, by reinforcing our small but vital existence, we also accept humanity.

I draw.

Sisyphus was condemned by the gods to eternally roll a rock up a mountain only to have it roll back down again under its own weight.

I draw.

Camus saw Sisyphus as an emblem of the seemingly absurd and relentless struggle against the obscure terms of our existence. He saw Sisyphus achieve his purpose only to watch in despair as the stone tumbled down. He saw Sisyphus walk back down the hill. It is during that return, Camus suggests, that the tragic hero is briefly freed. In acknowledging the futility of his task and the certainty of his fate, Sisyphus accepts that the struggle towards the heights is itself enough.

I draw.

“All is well”, Camus concludes. “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” [Camus, A. The Myth of Sisyphus, translated by Justin O’Brien, Penguin Books, 2000, p. 111.]

I draw.

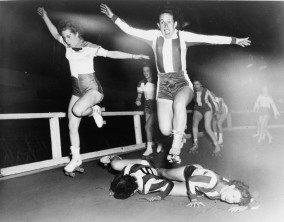

Individually, we are constantly embroiled in a struggle to maintain our own equilibrium through uncertainty, fear and the unknown. But like Sisyphus, we continue to push. To strain. To persevere, regardless of what may lie ahead. I am intensely interested in the human capacity to fight whatever forces we may encounter, whether within or beyond our mortal control. My figures are engaged. They struggle. Against what almost doesn’t matter.

I draw.

Making these hand drawn images with charcoal, perhaps the oldest known artistic medium, is an intensely laborious process. Again and again, charcoal meets paper. Time spent in the act of execution is essential to my practice. The struggle inherent in the creation of my work does, for me, not only reflect my own deep need to engage with the act of drawing, but also mirrors and substantiates the struggle of my protagonists. They will continue to battle for as long as they continue to be drawn into being.

And so I draw.

Kim Buck was born in Mount Gambier, South Australia. After studying Psychology and Science, Kim discovered a natural affinity for the medium of charcoal in 2006. Since graduating from the South Australian School of Art in 2009, she has had three sell out solo exhibitions and won a number of significant national prizes. Kim is represented by Peter Walker Fine Art (Adelaide), Jan Murphy Gallery (Brisbane) and Michael Reid Gallery (Sydney).

Prompt

Prompt

Dmitry Borshch

Dmitry Borshch