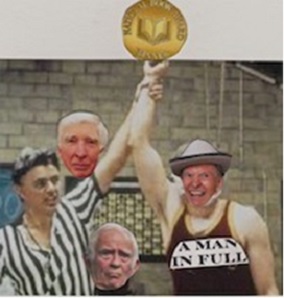

“I think of the three of them now as Larry, Curly & Moe.” Tom Wolfe, of John (Updike), John (Irving) & Norman (Mailer)

A century and a half after the Poe/English bout, three pedigreed but aging novelists shanked a colleague shorter than the Baltimore bete noire, but with a larger tongue and following.

Swords were first crossed when Tom Wolfe made millions on The Bonfire of the Vanities; but John Updike, John Irving, and Norman Mailer dismissed the novel as populist drivel. Wolfe counter-attacked with his 1989 Harper’s essay, “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast,” about a fiction Old Guard too fossilized to appreciate his revolutionary fiction nonfiction.[1]

Resentments seethed for a decade, and erupted again with Wolfe’s latest bestseller, A Man In Full.

“Entertainment, not literature,” sniped Updike in his New Yorker review, “even literature in a modest aspirant form.”[2]

“At certain points, reading the work can even be said to resemble the act of making love to a three-hundred-pound woman: Once she gets on top, it’s over. Fall in love, or be asphyxiated,”[3] argued Norman Mailer, speaking from the experience of tackling his own 1,310 page Amazon, Harlot’s Ghost. Man in Full tipped the scales at a mere 742. He went on to coronate his colleague as “the most gifted best-seller writer… since Margaret Mitchell.”

Wolfe dismissed the creators of Rabbit and Dear Park as “two piles of bones.”[4]

Their comrade-in-arms, John Irving, flew over the ropes and spelled the hyperventilating tag team. “I can’t read him,” he said of Wolfe, “because he’s such a bad writer.”

Now it was three against one — the hoopster, the headbutter, and the wrestler – against the diminutive dandy in full. “I think of the three of them now — because there are now three –as Larry, Curly and Moe,” he said. “It must gall them a bit that everyone — even them — is talking about me.”

“If I were teaching fucking freshman English,” Irving fumed, “I couldn’t read a sentence [of his] and not just carve it up.” When the Canadian TV Hot Type host asked if he was at war with the little man in white, Garp’s creator — overlooking a proletariat revolution or two — bristled, “I don’t think it’s a war because you can’t have a war between a pawn and a king, can you?”

But, in the end, the southern gentleman had the last word, aware that Irving and his stooges were the best PR reps he’d ever had. “Why does he sputter and foam so?” Wolfe wondered in a statement released by his publisher.[5]

In the mid-sixties, the 34-year-old heretic had published The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine- Flake Streamline Baby. The title, a collection of his pieces from the Washington Post and elsewhere, replete with exclamatories, ellipses, and neo-street speak, spawned The New Journalism. To create a buzz by tossing a Molotov cocktail over the battlements of the Bastille, he strode into his editor’s office at the Herald Tribune one morning and asked —

“How about blowing up The New Yorker, Clay?”

So the Tribune ran “Tiny Mummies! The True Story of the Ruler of 43rd Street’s Land of the Walking Dead,” Wolfe’s assault on the alma mater of his Moriartys – Larry, Curly, and Moe. It featured a portrait of editor, William Shawn, as head funeral director, surrounded by his dutiful retainers and embalmed guardians of literature, the Tiny Mummies. The satire had been inspired by The New Yorker’s invitation-only 40th anniversary party at the St. Regis, which the stooges had attended and Wolfe crashed.

Shawn, who received an advance copy, fired a letter off to the Tribune’s owner, Jock Whitney. He called the article “murderous and certainly libelous,” and demanded that it be pulled from Sunday’s upcoming edition. Jock declined.

The magazine called in its cavalry. The Tribune was barraged with diatribes from Muriel Spark, to J.D. Salinger, to The Elements of Style E.B. White himself. Then the magazine’s enforcer, Dwight MacDonald, fired off a 13,000-word polemic, “Parajournalism, or Tom Wolfe & His Magic Writing Machine,” for its sister publication, The New York Review of Books. MacDonald called Wolfe’s style “a bastard form, having it both ways, exploiting the factual authority of journalism and the atmospheric license of fiction.”[6]

When the smoke cleared, the magazine had a shiner, and Wolfe’s new Streamline Baby was a sensation.

Just as the man in full had pioneered a new literary form, he had bested a boxer-wrestler- hoopster tag team by means of a revolutionary literary sparring technique: JuJutsu. The gentle Eastern art of rechanneling the opponent’s own aggression against him.

“Bullshit reigns!” the new champion of American letters proclaimed in Bonfire of the Vanities.

[1] David Foster Wallace and Sven Birkerts reinforced Wolfe with their 1997 New York Observer “Twilight of the Phallocrats” denouncing “our arts-bemedaled senior novelists [Updike, Mailer, Bellow, and Roth]… as Great Male Narcissists.” In turn, the Observer’s Anne Roiphe denounced the young literary guns for “urinating” on G.M.N.S.’s out of their own “primitive” male competitiveness. (“Literary Dogs Snap Savagely at Top Dogs,” New York Observer, October 27, 1997)

[2] John Updike, “AWRIIIIIGHHHHHHHHH!” New Yorker magazine, November 9, 1998

[3] Norman Mailer, “A Man Half Full” The New York Review of Books. December 17, 1998

[4] The Charlotte Observer, November 1999 interview.

[5] Jim Windolf, “It’s Tom Wolfe Versus the ‘Three Stooges,” New York Observer, February7, 2000

[6] Dwight MacDonald , “Parajournalism, or Tom Wolfe & His Magic Writing Machine,” The New York Review of Books, August 26, 1965.

David Comfort has published three popular nonfiction titles from Simon & Schuster, and a fourth from Citadel/ Kensington. “Bards Behaving Badly” is excerpted from his latest trade title, An Insider’s Guide to Publishing, released by Writers Digest Books in December, 2013. Comfort is a Pushcart Fiction Prize nominee, and a finalist for the Faulkner Award, Chicago Tribune Nelson Algren, America’s Best, Narrative, Glimmer Train, Red Hen, Helicon Nine, and Heekin Graywolf Fellowship. His current short fiction appears in The Evergreen Review, Cortland Review, The Morning News, Scholars & Rogues, Inkwell, and Eclectica Magazine.

Mailer disdained Faulkner for his “mean small Southern streak” and for never saying anything “interesting,” but shared his supreme vanity and ambition.

Mailer disdained Faulkner for his “mean small Southern streak” and for never saying anything “interesting,” but shared his supreme vanity and ambition.