In the summer of 1977 in the small southern Georgia town of Valdosta, my mother stole the neighbor’s dog. I don’t remember much of Valdosta: wet, red clay dirt, snakes in the garden, everything green, everything humid, everything on the edge of rotting. Even voices had a sweet rind of decay. Years after we moved back north, I found a cassette recording my mother made of me counting. My “two” rhymed with “chew.” My “three” and “eight” lilted and stretched into two syllables. “Ten” could be confused for “tan.” By the time I discovered the tape, I no longer had an accent, and that recorded voice revealed a separate existence that was strange and gone.

My mother, Erika, also had an accent, but she didn’t lose it. Born in Hungary, she was ten when she came to the United States with her parents and sister. She was functionally deaf in one ear as the result of an accident with a sharp pencil. The hearing loss was never diagnosed, and when Erika had trouble learning English, her American teachers thought she was slow and put her in remedial classes. The deafness was eventually detected, and she was fitted for a hearing aid, but the mislabeling had an impact. To this day, she’ll be damned if she lets anyone call her stupid. But she never lost her Hungarian accent. Never lost the identifier that marked her as foreign.

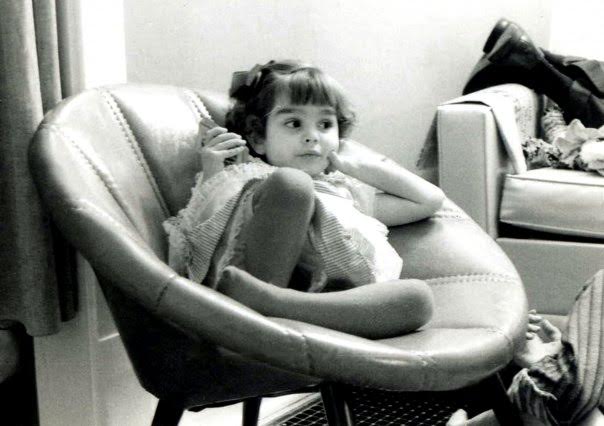

As a child, I didn’t know my mother had an accent. My mother’s voice was my origin of sound. I still don’t hear the accent unless I listen hard. But in the 1970s in the deep south, in a city nine miles south of Moody Air Force Base, my mother’s accent defined her. She was a stranger, seen and treated as an “other,” often with perceptible distaste, something she felt acutely.

My father, a CPA who worked for ITT Corporation, was raised in upstate New York by an Italian-American father who worked for the railroad and an Irish-American mother who spent her days herding seven children. While labeled a Yankee, he was, at least, American. His presence served as a social bridge in the neighborhood, but he wasn’t around much, and when Erika went to the grocery store or hauled two kids to the public library, she was on her own in a hostile territory that, through southern charm and expert dissembling, pretended it wasn’t hostile.

I didn’t know or sense any of this as a child. It was only when I was a teenager, loading the dishwasher in the house my parents bought when we returned to New York, that my mother revealed what her years in Georgia were like. I don’t recall what we were talking about when something I said opened up a wound. She told me about the slights and snubs in Georgia that rubbed her so regularly they formed a callous that protected and numbed her.

“I was alone except for you and your brother. You two were all I had,” she said.

The confession made me uncomfortable. I turned back to the dishes and my mother left the room. I hadn’t known, up to that point, that my mother could be hurt. Of everything that she was, of every quality she embodied, I knew my mother primarily—often solely—as strong. I thought she could only be angered.

***

The neighbor’s dog was a toy poodle named Suzy. She was alternately cared for and neglected by the Studdards, who had a son named Dean whom my brother Mark and I played with occasionally. I don’t remember much about Dean except that I had a vague understanding that he could be mean, and once, he hit me on the head with a stick when I was climbing up to the tree house. I fell and landed hard. My father came out, and there was yelling. I think my mother tried to limit the amount of time we spent with him, especially after Dean and I were discovered half-undressed beneath the Studdards’ trampoline. I tried to find Dean Studdard on the internet. There are two living in Georgia—both in Valdosta.

The Studdards’ house was directly behind ours, backyards adjacent, no fence. In addition to Suzy, they had a large, aging mutt they didn’t let inside. I would creep to the back of their house to fill an old trough beneath a spigot that served as his water bowl. I often found it near empty and would fill it as quietly as I could. I thought I’d get in trouble if someone spotted me.

My mother loved Suzy. She loved all animals, though we didn’t have any pets in Georgia, probably because of our transience. We had moved from New York to Houston to Memphis to Valdosta in a little under two years following my father’s job. Eventually, after we left Georgia and landed in New Jersey, my mother adopted a dog named Mooch and a cat named Choo-Choo, but in our house on Sherwood Drive just a few miles north of the Florida border, she had only Mark and me, creatures who required a more complex and demanding affection.

Despite our lack of pets, my mom stocked Gaines Burgers in our kitchen pantry, moisturized dog food shaped like hamburgers and made, as the box claimed, “with real meat!” I loved the feel of them—soft and mushy beneath the cellophane. My mother used the dog food to lure Suzy to our back door, and I would help her crumble half a burger into a little bowl. Like my act of filling the water trough, I knew what we were doing was good, but there was something in my mother’s manner that made me understand that it was also something illicit.

“They don’t feed her enough,” my mother would tell me as she put the bowl on the steps leading up to the back door. And Suzy, who had the run of both backyards, would make her way over and take delicate little bites. Afterward, Suzy would follow us into the house where she jumped onto the sofa and napped as my mother petted her. A little while later, she’d jump down and head back to the Studdards.

Suzy began to follow my mom around the yard, then into the house and around the kitchen as she prepared meals, smoking cigarettes and talking on the phone, a long twisted cord giving her access to the stove, refrigerator and counter. The click-click-click of Suzy’s nails on the kitchen linoleum became the soundtrack of quiet afternoons in an air-conditioned house shuttered and dark against the heat. I was confused and grew to think that Suzy was our dog, and my mother did little to clear up my confusion. The Studdards own Suzy, she’d tell me, but we take care of her, and she loves us more.

Eventually, Suzy started following Erika around the neighborhood. One afternoon, my mother took me across the street on a rare visit with a neighbor. She served us iced tea at a table next to a large, above-ground pool that I found incredibly luxurious. We were barely settled when Suzy came around the corner of the house. The neighbor’s dog, large and brutish, lunged and caught Suzy in its jaws, shaking her like a toy then flinging her across the yard. Suzy lay where she landed, not moving, bent and bloody.

My mother called the Studdards from the veterinarian’s office, told them what happened, told them how much it would cost to get Suzy fixed up. The Studdards refused to pay, telling my mom it was her fault, telling her to let the dog die. After she hung up with the Studdards, my mother called my father at the office. He said no. Hell, no, we’re not paying $300 for the neighbor’s dog. My mom cried. She hung up. Then my dad called her back at the vet’s office. He said okay. Go ahead. Get the damn surgery.

My mother loves to tell this story. She loves to talk about how my father pretended to hate animals but was really a softie. She credits him with a change of heart tied to his conscience. But I know my father was not a softie. He was a large, difficult man with a temper and whose rage was often terrifying. My mother just always got what she wanted. She still does.

***

A few years back, before my brother got divorced, his then wife called me in exasperation.

“I don’t understand,” she said. “Your brother is a grown-ass adult man, and he can’t make a single decision without talking to your mama first and getting her blessing. He has got to cut the apron strings.”

It’s funny to think about it. How my mother rules my brother. She’s a tiny woman—five feet, two inches and my brother is a huge, ball-busting, tough guy. Barrel-chested and muscular, he worked as a bouncer through college. He shoots guns. He can scare most people without trying too hard. And my mother can cripple him with a disapproving look. She owns him. There was very little comfort I could offer my sister-in-law because my mother owns me, too. And I suspect, back in 1976 when Suzy was mauled by the neighbor’s dog and wasn’t going to live without emergency surgery, my mother owned my father, as well.

I have always been in awe of my mother’s strength. In a certain light, it could be perceived as hard-headed stubbornness and self-righteousness. In a different light, her strength is born from a clear sense of justice and a refusal to be shamed. I suspect it is a mix of both. In 2007, when Mark and I were what passes for adults, my mother was working for the State of New York in a midlevel government job surrounded by people who watched TV at their desks. She forwarded a viral email to a group of coworkers. It contained a collection of cartoons, one of which featured a snowman with a carrot erection next to a snowwoman with large snowballs for breasts. There was probably a risqué quip beneath it. When my mom forwarded the message, she cut off the tail that showed the string of state employees who received it and forwarded it on before her.

One of her coworkers reported Erika for sexual harassment. I feel like I need to write that again. My 62-year-old mother was accused of sexual harassment. She was called into Human Resources (HR) with her supervisor and union representative. She was reprimanded and given an agreement that outlined disciplinary actions: a loss of two weeks’ vacation, probation, and a letter in her permanent file. Her supervisor and union representative counseled her to sign it. She refused and explained that she merely forwarded a stupid email that had been forwarded to her. HR asked her for the name of the person who sent it to her. She refused to name names. They explained that there was nothing else they could do. Erika still refused to sign the paper and asked for a hearing. Everyone left the room.

A few days later, her union representative called her and said that HR has decided to change the disciplinary action: one week of lost vacation instead of two. The representative urged her to accept the deal. Erika refused. She demanded a hearing. A few more days passed, and they offered a new deal: no vacation loss and a letter in her file. Still, Erika said no. Eventually, the case was dismissed with no action taken. My mother had waited them out and worn them down.

I often thought about how I would have responded, the acute shame of being accused, the stacked power differential of the people in the room, the risk of losing my job. Throughout the negotiations, my mom would laugh as she recounted the latest developments, but I was scandalized. Embarrassed. I thought her disregard for consequences was short-sighted. At the same time, I liked to think I would have fought it just as she did, would have advocated for myself, would have loudly proclaimed the ridiculousness of the situation and made a stink. Or maybe I would have been just as successful in my own way, using diplomacy and reason, appeasing the offended without acknowledging the offense. But even then I knew better. In many ways, I was not my mother’s daughter. I was meek. I rolled over. I would not have fared well.

***

When my mother brought Suzy back from the veterinarian, the dog had a cast around her entire torso. I was delighted by the cast, the contrast between the hard, cool shell of the plaster and Suzy’s warm, wriggly body inside it. Suzy stayed with us, and my mother nursed her, made a little bed for her that she carried from room to room, so Suzy wouldn’t be alone. Nobody heard from the Studdards.

Suzy recovered quickly and was soon up and about, carefully making her way down the back patio steps to sniff around the backyard as my mother gardened. The cast was removed after a few weeks, along with the stitches. My mom brought Suzy home, and we fed her Gaines Burgers as she pranced in and out of the kitchen, jumping on and off the couch in pleasure. Later that day, we heard a knock at the back door. Dean Studdard stood there, his face set in a grimace.

“We want our dog back,” he said.

“You tell your parents that they can have Suzy back when they pay me for the vet bills,” my mom answered.

Dean glared and turned away, and we watched him walk across the backyards to his house. Shortly after, the phone rang, and my mom launched into a heated exchange with Dean’s mom who slung xenophobic slurs and threats involving the police. My mom called my dad. He talked about the neighborhood, not wanting to make enemies, not wanting to involve law enforcement, especially when, he suspected, we wouldn’t win.

“Give the dog back,” he said. “She’s not our dog.”

My mom gave Suzy back.

***

A few months later, my dad was transferred to New Jersey. My parents flew north to look at houses, and my grandmother flew south to watch Mark and me. My dad stayed north while my mother returned to pack up the house and to send my grandmother back home. In the last few days of boxes and moving vans and goodbyes, the Studdards called my mom to see if she had Suzy. The dog was missing. My mom said no and offered to look, saying with wicked pleasure that Suzy may be more likely to come if she heard my mom calling. We all wandered the neighborhood for hours calling for Suzy. No one could find her. Mark and I worried that she had gotten attacked by a large dog or hit by a car or that she would return to find our house empty and that we left without saying goodbye. Our mother told us there wasn’t much else she could do.

We left Georgia a few days later. My father flew back and we all drove north to my grandparents’ house in New York where my brother and I would stay until the new house was ready. It was a 20-hour drive and we were all hot, grumpy, hungry and tired when we arrived. My brother and I ran through the mudroom, burst through the kitchen door, and were astounded to see Suzy prancing around my grandmother’s feet in excitement.

“Suzy!” we shouted.

“Not Suzy,” my mother said, following us. “Susie.”

We looked at her in confusion.

“Grandma loved Suzy so much, she decided to get a toy poodle that looked just like her,” my mother explained. “And she named her ‘Susie,’ which is Hungarian for ‘Suzy.’”

We looked from my mother’s face to my grandmother’s and back to my mother’s. They both nodded.

“Susie!” we cried.

“Her nails are blue!” I shouted. “They match her ribbon!”

“I took her to the dog groomer,” Grandma said.

Mark and I understood completely. We thought Suzy was great, but Susie was ours, and no one was going to take her away.

***

It wasn’t until I was a teenager and both my father and Susie had long since died that I realized that Susie and Suzy were the same dog. I don’t remember what prompted the connection, but when I asked my mom, she laughed and said, “Of course! I wasn’t going to leave Suzy behind. She would have died.”

“But how did you do it,” I asked.

“Oh, it was a pain in the ass. We shipped her by plane to New York. It was really expensive. Your father almost had a stroke. We had to buy the crate, pay special fees. I worked it all out with your grandmother in advance. She picked her up at the airport in Albany.”

“So when Suzy was missing and we were all looking for her, you knew she was on a plane to New York?”

“Oh, by that time, I think she was already in New York.” She laughed again and pulled impish faces at the memory.

“Mom, you stole a dog,” I said.

“I did!” She leaned back and laughed. “But she was our dog. We loved her. She loved us. Love made her ours.”

***

I am still, in many ways, not my mother’s daughter. I am still meek. I often do not get my way, and almost as often don’t mind. I usually think of my pliancy as a good quality, but as an old friend once told me, there’s a dark side to every mountain. But the dark side is hard to see.

Last year, I found myself struggling in my job after a new executive director took over. In my first job review with her, she failed me in every category. Two of the categories I had “substantially failed.” The level-headed part of my brain knew this was ludicrous. Anyone with a modicum of intelligence and a smidge of work ethic couldn’t fail everything. I knew something was up. I got angry. Like my mother, I refused to sign the review. And then I crumpled.

The executive director emailed me a note saying that I should submit a detailed outline describing the actions I would take to meet all expectations. She wrote as if to an incompetent idiot. The next day, I diligently toiled on a work plan to address my inadequacies and shortcomings. I addressed my communication problems that included things like “too many sentences.” I acknowledged my inefficiencies and ineffectiveness and owned it all. It was a humiliating process. I saved the document and planned to send it on Monday. Then I left for the weekend.

I spent two days crying randomly in public places. The job wasn’t ideal, but it was a work-from-home position with flexible hours, and I was a one-parent household struggling to be the type of mother I thought I should be. I was terrified of losing my job, couldn’t imagine anyone else hiring me. I couldn’t fathom how I failed so spectacularly. I didn’t know what to do.

When I sat back down at my desk on Monday and opened up the document, I thought about my mother. Her stubbornness that was sometimes brave, sometimes foolish. Her anger that was sometimes ugly but always strong. I looked at all the steps I outlined to show my boss how I would do my job better. I felt gross and ashamed. It was time to feel something else. It was time to be my mother’s daughter. It was time to steal the goddamn dog.

##