I

On 25 March an unusually strange event occurred in St. Petersburg. For that morning Barber Ivan Yakovlevitch, a dweller on the Vozkresensky Prospekt (his name is lost now—it no longer figures on a signboard bearing a portrait of a gentleman with a soaped cheek, and the words: “Also, Blood Let Here”)—for that morning Barber Ivan Yakovlevitch awoke early, and caught the smell of newly baked bread. Raising himself a little, he perceived his wife (a most respectable dame, and one especially fond of coffee) to be just in the act of drawing newly baked rolls from the oven.

“Prascovia Osipovna,” he said, “I would rather not have any coffee for breakfast, but, instead, a hot roll and an onion,”—the truth being that he wanted both but knew it to be useless to ask for two things at once, as Prascovia Osipovna did not fancy such tricks.

“Oh, the fool shall have his bread,” the dame reflected. “So much the better for me then, as I shall be able to drink a second lot of coffee.”

And duly she threw on to the table a roll.

Ivan Yakovlevitch donned a jacket over his shirt for politeness’ sake, and, seating himself at the table, poured out salt, got a couple of onions ready, took a knife into his hand, assumed an air of importance, and cut the roll asunder. Then he glanced into the roll’s middle. To his intense surprise he saw something glimmering there. He probed it cautiously with the knife—then poked at it with a finger.

“Quite solid it is!” he muttered. “What in the world is it likely to be?”

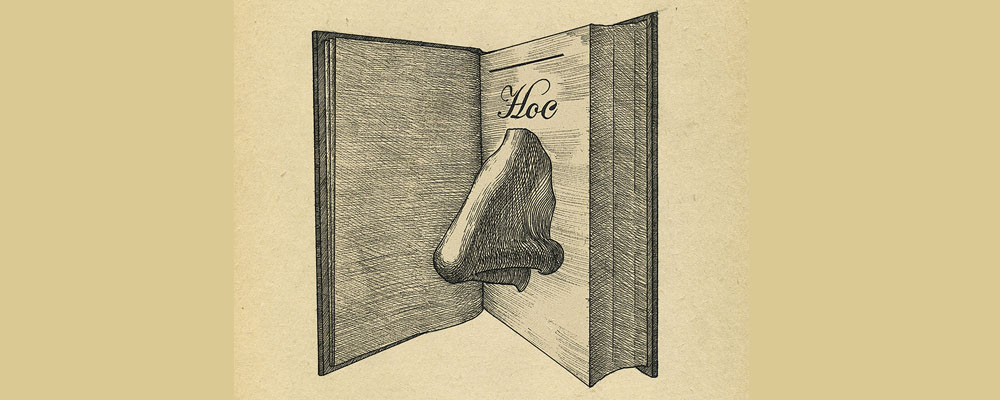

He thrust in, this time, all his fingers, and pulled forth—a nose! His hands dropped to his sides for a moment. Then he rubbed his eyes hard. Then again he probed the thing. A nose! Sheerly a nose! Yes, and one familiar to him, somehow! Oh, horror spread upon his feature! Yet that horror was a trifle compared with his spouse’s overmastering wrath.

“You brute!” she shouted frantically. “Where have you cut off that nose? You villain, you! You drunkard! Why, I’ll go and report you to the police myself. The brigand, you! Three customers have told me already about your pulling at their noses as you shaved them till they could hardly stand it.”

But Ivan Yakovlevitch was neither alive nor dead. This was the more the case because, sure enough, he had recognised the nose. It was the nose of Collegiate Assessor Kovalev—no less: it was the nose of a gentleman whom he was accustomed to shave twice weekly, on each Wednesday and each Sunday!

“Stop, Prascovia Osipovna!” at length he said. “I’ll wrap the thing in a clout, and lay it aside awhile, and take it away altogether later.”

“But I won’t hear of such a thing being done! As if I’m going to have a cut-off nose kicking about my room! Oh, you old stick! Maybe you can just strop a razor still; but soon you’ll be no good at all for the rest of your work. You loafer, you wastrel, you bungler, you blockhead! Aye, I’ll tell the police of you. Take it away, then. Take it away. Take it anywhere you like. Oh, that I’d never caught the smell of it!”

Ivan Yakovlevitch was dumbfounded. He thought and thought, but did not know what to think.

“The devil knows how it’s happened,” he said, scratching one ear. “You see, I don’t know for certain whether I came home drunk last night or not. But certainly things look as though something out of the way happened then, for bread comes of baking, and a nose of something else altogether. Oh, I just can’t make it out.”

So he sat silent. At the thought that the police might find the nose at his place, and arrest him, he felt frantic. Yes, already he could see the red collar with the smart silver braiding—the sword! He shuddered from head to foot.

But at last he got out, and donned waistcoat and shoes, wrapped the nose in a clout, and departed amid Prascovia Osipovna’s forcible objurgations.

His one idea was to rid himself of the nose, and return quietly home—to do so either by throwing the nose into the gutter in front of the gates or by just letting it drop anywhere. Yet, unfortunately, he kept meeting friends, and they kept saying to him: “Where are you off to?” or “Whom have you arranged to shave at this early hour?” until seizure of a fitting moment became impossible. Once, true, he did succeed in dropping the thing, but no sooner had he done so than a constable pointed at him with his truncheon, and shouted: “Pick it up again! You’ve lost something,” and he perforce had to take the nose into his possession once more, and stuff it into a pocket. Meanwhile his desperation grew in proportion as more and more booths and shops opened for business, and more and more people appeared in the street.

At last he decided that he would go to the Isaakievsky Bridge, and throw the thing, if he could, into the Neva. But here let me confess my fault in not having said more about Ivan Yakovlevitch himself, a man estimable in more respects than one.

Like every decent Russian tradesman, Ivan Yakovlevitch was a terrible tippler. Daily he shaved the chins of others, but always his own was unshorn, and his jacket (he never wore a top-coat) piebald—black, thickly studded with greyish, brownish-yellowish stains—and shiny of collar, and adorned with three pendent tufts of thread instead of buttons. But, with that, Ivan Yakovlevitch was a great cynic. Whenever Collegiate Assessor Kovalev was being shaved, and said to him, according to custom: “Ivan Yakovlevitch, your hands do smell!” he would retort: “But why should they smell?” and, when the Collegiate Assessor had replied: “Really I do not know, brother, but at all events they do,” take a pinch of snuff, and soap the Collegiate Assessor upon cheek, and under nose, and behind ears, and around chin at his good will and pleasure.

So the worthy citizen stood on the Isaakievsky Bridge, and looked about him. Then, leaning over the parapet, he feigned to be trying to see if any fish were passing underneath. Then gently he cast forth the nose.

At once ten puds-weight seemed to have been lifted from his shoulders. Actually he smiled! But, instead of departing, next, to shave the chins of chinovniki, he bethought him of making for a certain establishment inscribed “Meals and Tea,” that he might get there a glassful of punch.

Suddenly he sighted a constable standing at the end of the bridge, a constable of smart appearance, with long whiskers, a three-cornered hat, and a sword complete. Oh, Ivan Yakovlevitch could have fainted! Then the constable, beckoning with a finger, cried:

“Nay, my good man. Come here.”

Ivan Yaklovlevitch, knowing the proprieties, pulled off his cap at quite a distance away, advanced quickly, and said:

“I wish your Excellency the best of health.”

“No, no! None of that `your Excellency,’ brother. Come and tell me what you have been doing on the bridge.”

“Before God, sir, I was crossing it on my way to some customers when I peeped to see if there were any fish jumping.”

“You lie, brother! You lie! You won’t get out of it like that. Be so good as to answer me truthfully.”

“Oh, twice a week in future I’ll shave you for nothing. Aye, or even three times a week.”

“No, no, friend. That is rubbish. Already I’ve got three barbers for the purpose, and all of them account it an honour. Now, tell me, I ask again, what you have just been doing?”

This made Ivan Yakovlevitch blanch, and—

Further events here become enshrouded in mist. What happened after that is unknown to all men._

II

COLLEGIATE ASSESSOR KOVALEV also awoke early that morning. And when he had done so he made the “B-r-rh!” with his lips which he always did when he had been asleep—he himself could not have said why. Then he stretched himself, had handed to him a small mirror from the table near by, and set himself to inspect a pimple which had broken out on his nose the night before. But, to his unbounded astonishment, there was only a flat patch on his face where the nose should have been! Greatly alarmed, he called for water, washed, and rubbed his eyes hard with the towel. Yes, the nose indeed was gone! He prodded the spot with a hand-pinched himself to make sure that he was not still asleep. But no; he was not still sleeping. Then he leapt from the bed, and shook himself. No nose had he on him still! Finally, he bade his clothes be handed him, and set forth for the office of the Police Commissioner at his utmost speed.

Here let me add something which may enable the reader to perceive just what the Collegiate Assessor was like. Of course, it goes without saying that Collegiate Assessors who acquire the title with the help of academic diplomas cannot be compared with Collegiate Assessors who become Collegiate Assessors through service in the Caucasus, for the two species are wholly distinct, they are—Stay, though. Russia is so strange a country that, let one but say anything about any one Collegiate Assessor, and the rest, from Riga to Kamchatka, at once apply the remark to themselves—for all titles and all ranks it means the same thing. Now, Kovalev was a “Caucasian” Collegiate Assessor, and had, as yet, borne the title for two years only. Hence, unable ever to forget it, he sought the more to give himself dignity and weight by calling himself, in addition to “Collegiate Assessor,” “Major.”

“Look here, good woman,” once he said to a shirts’ vendor whom he met in the street, “come and see me at my home. I have my flat in Sadovaia Street. Ask merely, `Is this where Major Kovalev lives?’ Anyone will show you.” Or, on meeting fashionable ladies, he would say: “My dear madam, ask for Major Kovalev’s flat.” So we too will call the Collegiate Assessor “Major.”

Major Kovalev had a habit of daily promenading the Nevsky Prospekt in an extremely clean and well-starched shirt and collar, and in whiskers of the sort still observable on provincial surveyors, architects, regimental doctors, other officials, and all men who have round, red cheeks, and play a good hand at “Boston.” Such whiskers run across the exact centre of the cheek—then head straight for the nose. Again, Major Kovalev always had on him a quantity of seals, both of seals engraved with coats of arms, and of seals inscribed “Wednesday,” “Thursday,” “Monday,” and the rest. And, finally, Major Kovalev had come to live in St. Petersburg because of necessity. That is to say, he had come to live in St. Petersburg because he wished to obtain a post befitting his new title—whether a Vice-Governorship or, failing that, an Administratorship in a leading department. Nor was Major Kovalev altogether set against marriage. Merely he required that his bride should possess not less than two hundred thousand rubles in capital. The reader, therefore, can now judge how the Major was situated when he perceived that instead of a not unpresentable nose there was figuring on his face an extremely uncouth, and perfectly smooth and uniform patch.

Ill luck prescribed, that morning, that not a cab was visible throughout the street’s whole length; so, huddling himself up in his cloak, and covering his face with a handkerchief (to make things look as though his nose were bleeding), he had to start upon his way on foot only.

“Perhaps this is only imagination?” he reflected. Presently he turned aside towards a restaurant (for he wished yet again to get a sight of himself in a mirror). “The nose can’t have removed itself of sheer idiocy.”

Luckily no customers were present in the restaurant—merely some waiters were sweeping out the rooms, and rearranging the chairs, and others, sleepy-eyed fellows, were setting forth trayfuls of hot pastries. On chairs and tables last night’s newspapers, coffee-stained, were strewn.

“Thank God that no one is here!” the Major reflected. “Now I can look at myself again.”

He approached a mirror in some trepidation, and peeped therein. Then he spat.

“The devil only knows what this vileness means!” he muttered. “If even there had been something to take the nose’s place! But, as it is, there’s nothing there at all.”

He bit his lips with vexation, and hurried out of the restaurant. No; as he went along he must look at no one, and smile at no one. Then he halted as though riveted to earth. For in front of the doors of a mansion he saw occur a phenomenon of which, simply, no explanation was possible. Before that mansion there stopped a carriage. And then a door of the carriage opened, and there leapt thence, huddling himself up, a uniformed gentleman, and that uniformed gentleman ran headlong up the mansion’s entrance-steps, and disappeared within. And oh, Kovalev’s horror and astonishment to perceive that the gentleman was none other than—his own nose! The unlooked-for spectacle made everything swim before his eyes. Scarcely, for a moment, could he even stand. Then, deciding that at all costs he must await the gentleman’s return to the carriage, he remained where he was, shaking as though with fever. Sure enough, the Nose did return, two minutes later. It was clad in a gold-braided, high-collared uniform, buckskin breeches, and cockaded hat. And slung beside it there was a sword, and from the cockade on the hat it could be inferred that the Nose was purporting to pass for a State Councillor. It seemed now to be going to pay another visit somewhere. At all events it glanced about it, and then, shouting to the coachman, “Drive up here,” re-entered the vehicle, and set forth.

Poor Kovalev felt almost demented. The astounding event left him utterly at a loss. For how could the nose which had been on his face but yesterday, and able then neither to drive nor to walk independently, now be going about in uniform?—He started in pursuit of the carriage, which, luckily, did not go far, and soon halted before the Gostiny Dvor.[*]

[* Formerly the “Whiteley’s” of St. Petersburg.]

Kovalev too hastened to the building, pushed through the line of old beggar-women with bandaged faces and apertures for eyes whom he had so often scorned, and entered. Only a few customers were present, but Kovalev felt so upset that for a while he could decide upon no course of action save to scan every corner in the gentleman’s pursuit. At last he sighted him again, standing before a counter, and, with face hidden altogether behind the uniform’s stand-up collar, inspecting with absorbed attention some wares.

“How, even so, am I to approach it?” Kovalev reflected. “Everything about it, uniform, hat, and all, seems to show that it is a State Councillor now. Only the devil knows what is to be done!”

He started to cough in the Nose’s vicinity, but the Nose did not change its position for a single moment.

“My good sir,” at length Kovalev said, compelling himself to boldness, “my good sir, I—”

“What do you want?” And the Nose did then turn round.

“My good sir, I am in a difficulty. Yet somehow, I think, I think, that—well, I think that you ought to know your proper place better. All at once, you see, I find you—where? Do you not feel as I do about it?”

“Pardon me, but I cannot apprehend your meaning. Pray explain further.”

“Yes, but how, I should like to know?” Kovalev thought to himself. Then, again taking courage, he went: on:

“I am, you see—well, in point of fact, you see, I am a Major. Hence you will realise how unbecoming it is for me to have to walk about without a nose. Of course, a peddler of oranges on the Vozkresensky Bridge could sit there noseless well enough, but I myself am hoping soon to receive a—Hm, yes. Also, I have amongst my acquaintances several ladies of good houses (Madame Chektareva, wife of the State Councillor, for example), and you may judge for yourself what that alone signifies. Good sir”—Major Kovalev gave his shoulders a shrug—”I do not know whether you yourself (pardon me) consider conduct of this sort to be altogether in accordance with the rules of duty and honour, but at least you can understand that—”

“I understand nothing at all,” the Nose broke in. “Explain yourself more satisfactorily.”

“Good sir,” Kovalev went on with a heightened sense of dignity, “the one who is at a loss to understand the other is I. But at least the immediate point should be plain, unless you are determined to have it otherwise. Merely—you are my own nose.”

The Nose regarded the Major, and contracted its brows a little.

“My dear sir, you speak in error,” was its reply. “I am just myself—myself separately. And in any case there cannot ever have existed a close relation between us, for, judging from the buttons of your undress uniform, your service is being performed in another department than my own.”

And the Nose definitely turned away.

Kovalev stood dumbfounded. What to do, even what to think, he had not a notion.

Presently the agreeable swish of ladies’ dresses began to be heard. Yes, an elderly, lace-bedecked dame was approaching, and, with her, a slender maiden in a white frock which outlined delightfully a trim figure, and, above it, a straw hat of a lightness as of pastry. Behind them there came, stopping every now and then to open a snuffbox, a tall, whiskered beau in quite a twelve-fold collar.

Kovalev moved a little nearer, pulled up the collar of his shirt, straightened the seals on his gold watch-chain, smiled, and directed special attention towards the slender lady as, swaying like a floweret in spring, she kept raising to her brows a little white hand with fingers almost of transparency. And Kovalev’s smiles became broader still when peeping from under the hat he saw there to be an alabaster, rounded little chin, and part of a cheek flushed like an early rose. But all at once he recoiled as though scorched, for all at once he had remembered that he had not a nose on him, but nothing at all. So, with tears forcing themselves upwards, he wheeled about to tell the uniformed gentleman that he, the uniformed gentleman, was no State Councillor, but an impostor and a knave and a villain and the Major’s own nose. But the Nose, behold, was gone! That very moment had it driven away to, presumably, pay another visit.

This drove Kovalev to the last pitch of desperation. He went back to the mansion, and stationed himself under its portico, in the hope that, by peering hither and thither, hither and thither, he might once more see the Nose appear. But, well though he remembered the Nose’s cockaded hat and gold-braided uniform, he had failed at the time to note also its cloak, the colour of its horses, the make of its carriage, the look of the lackey seated behind, and the pattern of the lackey’s livery. Besides, so many carriages were moving swiftly up and down the street that it would have been impossible to note them all, and equally so to have stopped any one of them. Meanwhile, as the day was fine and sunny, the Prospekt was thronged with pedestrians also—a whole kaleidoscopic stream of ladies was flowing along the pavements, from Police Headquarters to the Anitchkin Bridge. There one could descry an Aulic Councillor whom Kovalev knew well. A gentleman he was whom Kovalev always addressed as “Lieutenant-Colonel,” and especially in the presence of others. And there there went Yaryzhkin, Chief Clerk to the Senate, a crony who always rendered forfeit at “Boston” on playing an eight. And, lastly, a like “Major” with Kovalev, a like “Major” with an Assessorship acquired through Caucasian service, started to beckon to Kovalev with a finger!

“The devil take him!” was Kovalev’s muttered comment. “Hi, cabman! Drive to the Police Commissioner’s direct.”

But just when he was entering the drozhki he added:

“No. Go by Ivanovskaia Street.”

“Is the Commissioner in?” he asked on crossing the threshold.

“He is not,” was the doorkeeper’s reply. “He’s gone this very moment.”

“There’s luck for you!”

“Aye,” the doorkeeper went on. “Only just a moment ago he was off. If you’d been a bare half-minute sooner you’d have found him at home, maybe.”

Still holding the handkerchief to his face, Kovalev returned to the cab, and cried wildly:

“Drive on!”

“Where to, though?” the cabman inquired.

“Oh, straight ahead!”

“‘Straight ahead’? But the street divides here. To right, or to left?”

The question caused Kovalov to pause and recollect himself. In his situation he ought to make his next step an application to the Board of Discipline—not because the Board was directly connected with the police, but because its dispositions would be executed more speedily than in other departments. To seek satisfaction of the the actual department in which the Nose had declared itself to be serving would be sheerly unwise, since from the Nose’s very replies it was clear that it was the sort of individual who held nothing sacred, and, in that event, might lie as unconscionably as it had lied in asserting itself never to have figured in its proprietor’s company. Kovalev, therefore, decided to seek the Board of Discipline. But just as he was on the point of being driven thither there occurred to him the thought that the impostor and knave who had behaved so shamelessly during the late encounter might even now be using the time to get out of the city, and that in that case all further pursuit of the rogue would become vain, or at all events last for, God preserve us! a full month. So at last, left only to the guidance of Providence, the Major resolved to make for a newspaper office, and publish a circumstantial description of the Nose in such good time that anyone meeting with the truant might at once be able either to restore it to him or to give information as to its whereabouts. So he not only directed the cabman to the newspaper office, but, all the way thither, prodded him in the back, and shouted: “Hurry up, you rascal! Hurry up, you rogue!” whilst the cabman intermittently responded: “Aye, barin,” and nodded, and plucked at the reins of a steed as shaggy as a spaniel.

The moment that the drozhki halted Kovalev dashed, breathless, into a small reception-office. There, seated at a table, a grey-headed clerk in ancient jacket and pair of spectacles was, with pen tucked between lips, counting sums received in copper.

“Who here takes the advertisements?” Kovalev exclaimed as he entered. “A-ah! Good day to you.”

“And my respects,” the grey-headed clerk replied, raising his eyes for an instant, and then lowering them again to the spread out copper heaps.

“I want you to publish—”

“Pardon—one moment.” And the clerk with one hand committed to paper a figure, and with a finger of the other hand shifted two accounts markers. Standing beside him with an advertisement in his hands, a footman in a laced coat, and sufficiently smart to seem to be in service in an aristocratic mansion, now thought well to display some knowingness.

“Sir,” he said to the clerk, “I do assure you that the puppy is not worth eight grivni even. At all events I wouldn’t give that much for it. Yet the countess loves it—yes, just loves it, by God! Anyone wanting it of her will have to pay a hundred rubles. Well, to tell the truth between you and me, people’s tastes differ. Of course, if one’s a sportsman one keeps a setter or a spaniel. And in that case don’t you spare five hundred rubles, or even give a thousand, if the dog is a good one.”

The worthy clerk listened with gravity, yet none the less accomplished a calculation of the number of letters in the advertisement brought. On either side there was a group of charwomen, shop assistants, doorkeepers, and the like. All had similar advertisements in their hands, with one of the documents to notify that a coachman of good character was about to be disengaged, and another one to advertise a koliaska imported from Paris in 1814, and only slightly used since, and another one a maid-servant of nineteen experienced in laundry work, but prepared also for other jobs, and another one a sound drozhki save that a spring was lacking, and another one a grey-dappled, spirited horse of the age of seventeen, and another one some turnip and radish seed just received from London, and another one a country house with every amenity, stabling for two horses, and sufficient space for the laying out of a fine birch or spruce plantation, and another one some second-hand footwear, with, added, an invitation to attend the daily auction sale from eight o’clock to three. The room where the company thus stood gathered together was small, and its atmosphere confined; but this closeness, of course, Collegiate Assessor Kovalev never perceived, for, in addition to his face being muffled in a handkerchief, his nose was gone, and God only knew its present habitat!

“My dear sir,” at last he said impatiently, “allow me to ask you something: it is a pressing matter.”

“One moment, one moment! Two rubles, forty-three kopeks. Yes, presently. Sixty rubles, four kopeks.”

With which the clerk threw the two advertisements concerned towards the group of charwomen and the rest, and turned to Kovalev.

“Well?” he said. “What do you want?”

“Your pardon,” replied Kovalev, “but fraud and knavery has been done. I still cannot understand the affair, but wish to announce that anyone returning me the rascal shall receive an adequate reward.”

“Your name, if you would be so good?”

“No, no. What can my name matter? I cannot tell it you. I know many acquaintances such as Madame Chektareva (wife of the State Councillor) and Pelagea Grigorievna Podtochina (wife of the Staff-Officer), and, the Lord preserve us, they would learn of the affair at once. So say just `a Collegiate Assessor,’ or, better, `a gentleman ranking as Major.'”

“Has a household serf of yours absconded, then?”

“A household serf of mine? As though even a household serf would perpetrate such a crime as the present one! No, indeed! It is my nose that has absconded from me.”

“Gospodin Nossov, Gospoding Nossov? Indeed a strange name, that![*] Then has this Gospodin Nossov robbed you of some money?”

[* Nose is noss in Russian, and Gospodin equivalent to the English “Mr.”]

“I said nose, not Nossov. You are making a mistake. There has disappeared, goodness knows whither, my nose, my own actual nose. Presumably it is trying to make a fool of me.”

“But how could it so disappear? The matter has something about it which I do not fully understand.”

“I cannot tell you the exact how. The point is that now the nose is driving about the city, and giving itself out for a State Councillor—wherefore I beg you to announce that anyone apprehending any such nose ought at once, in the shortest possible space of time, to return it to myself. Surely you can judge what it is for me meanwhile to be lacking such a conspicuous portion of my frame? For a nose is not like a toe which one can keep inside a boot, and hide the absence of if it is not there. Besides, every Thurdsay I am due to call upon Madame Chektareva (wife of the State Councillor): whilst Pelagea Grigorievna Podtochina (wife of the Staff-Officer, mother of a pretty daughter) also is one of my closest acquaintances. So, again, judge for yourself how I am situated at present. In such a condition as this I could not possibly present myself before the ladies named.”

Upon that the clerk became thoughtful: the fact was clear from his tightly compressed lips alone.

“No,” he said at length. “Insert such an announcement I cannot.”

“But why not?”

“Because, you see, it might injure the paper’s reputation. Imagine if everyone were to start proclaiming a disappearance of his nose! People would begin to say that, that—well, that we printed absurdities and false tales.”

“But how is this matter a false tale? Nothing of the sort has it got about it.”

“You think not; but only last week a similar case occurred. One day a chinovnik brought us an advertisement as you have done. The cost would have been only two rubles, seventy-three kopeks, for all that it seemed to signify was the running away of a poodle. Yet what was it, do you think, in reality? Why, the thing turned out to be a libel, and the `poodle’ in question a cashier—of what department precisely I do not know.”

“Yes, but here am I advertising not about a poodle, but about my own nose, which, surely, is, for all intents and purposes, myself?”

“All the same, I cannot insert the advertisement.”

“Even when actually I have lost my own nose!”

“The fact that your nose is gone is a matter for a doctor. There are doctors, I have heard, who can fit one out with any sort of nose one likes. I take it that by nature you are a wag, and like playing jokes in public.”

“That is not so. I swear it as God is holy. In fact, as things have gone so far, I will let you see for yourself.”

“Why trouble?” Here the clerk took some snuff before adding with, nevertheless, a certain movement of curiosity: “However, if it really won’t trouble you at all, a sight of the spot would gratify me.”

The Collegiate Assessor removed the handkerchief.

“Strange indeed! Very strange indeed!” the clerk exclaimed. “And the patch is as uniform as a newly fried pancake, almost unbelievably uniform.”

“So you will dispute what I say no longer? Then surely you cannot but put the announcement into print. I shall be extremely grateful to you, and glad that the present occasion has given me such a pleasure as the making of your acquaintance”—whence it will be seen that for once the Major had decided to climb down.

“To print what you want is nothing much,” the clerk replied. “Yet frankly I cannot see how you are going to benefit from the step. I would suggest, rather, that you commission a skilled writer to compose an article describing this as a rare product of nature, and have the article published in The Northern Bee” (here the clerk took more snuff), “either for the instruction of our young” (the clerk wiped his nose for a finish) “or as a matter of general interest.”

This again depressed the Collegiate Assessor: and even though, on his eyes happening to fall upon a copy of the newspaper, and reach the column assigned to theatrical news, and encounter the name of a beautiful actress, so that he almost broke into a smile, and a hand began to finger a pocket for a Treasury note (since he held that only stalls were seats befitting Majors and so forth)—although all this was so, there again recurred to him the thought of the nose, and everything again became spoilt.

Even the clerk seemed touched with the awkwardness of Kovalev’s plight, and wishful to lighten with a few sympathetic words the Collegiate Assessor’s depression.

“I am sorry indeed that this has befallen,” he said. “Should you care for a pinch of this? Snuff can dissipate both headache and low spirits. Nay, it is good for haemorrhoids as well.”

And he proffered his box-deftly, as he did so, folding back underneath it the lid depicting a lady in a hat.

Kovalev lost his last shred of patience at the thoughtless act, and said heatedly:

“How you can think fit thus to jest I cannot imagine. For surely you perceive me no longer to be in possession of a means of sniffing? Oh, you and your snuff can go to hell! Even the sight of it is more than I can bear. I should say the same even if you were offering me, not wretched birch bark, but real rappee.”

Greatly incensed, he rushed out of the office, and made for the ward police inspector’s residence. Unfortunately he arrived at the very moment when the inspector, after a yawn and a stretch, was reflecting: “Now for two hours’ sleep!” In short, the Collegiate Assessor’s visit chanced to be exceedingly ill-timed. Incidentally, the inspector, though a great patron of manufacturers and the arts, preferred still more a Treasury note.

“That’s the thing!” he frequently would say. “It’s a thing which can’t be beaten anywhere, for it wants nothing at all to eat, and it takes up very little room, and it fits easily to the pocket, and it doesn’t break in pieces if it happens to be dropped.”

So the inspector received Kovalev very drily, and intimated that just after dinner was not the best moment for beginning an inquiry—nature had ordained that one should rest after food (which showed the Collegiate Assessor that at least the inspector had some knowledge of sages’ old saws), and that in any case no one would purloin the nose of a really respectable man.

Yes, the inspector gave it Kovalev between the eyes. And as it should be added that Kovalev was extremely sensitive where his title or his dignity was concerned (though he readily pardoned anything said against himself personally, and even held, with regard to stage plays, that, whilst Staff-Officers should not be assailed, officers of lesser rank might be referred to), the police inspector’s reception so took him aback that, in a dignified way, and with hands set apart a little, he nodded, remarked: “After your insulting observations there is nothing which I wish to add,” and betook himself away again.

He reached home scarcely hearing his own footsteps. Dusk had fallen, and, after the unsuccessful questings, his flat looked truly dreary. As he entered the hall he perceived Ivan, his valet, to be lying on his back on the stained old leathern divan, and spitting at the ceiling with not a little skill as regards successively hitting the same spot. The man’s coolness rearoused Kovalev’s ire, and, smacking him over the head with his hat, he shouted:

“You utter pig! You do nothing but play the fool.” Leaping up, Ivan hastened to take his master’s cloak.

The tired and despondent Major then sought his sitting-room, threw himself into an easy-chair, sighed, and said to himself:

“My God, my God! why has this misfortune come upon me? Even loss of hands or feet would have been better, for a man without a nose is the devil knows what—a bird, but not a bird, a citizen, but not a citizen, a thing just to be thrown out of window. It would have been better, too, to have had my nose cut off in action, or in a duel, or through my own act: whereas here is the nose gone with nothing to show for it—uselessly—for not a groat’s profit!—No, though,” he added after thought, “it’s not likely that the nose is gone for good: it’s not likely at all. And quite probably I am dreaming all this, or am fuddled. It may be that when I came home yesterday I drank the vodka with which I rub my chin after shaving instead of water—snatched up the stuff because that fool Ivan was not there to receive me.”

So he sought to ascertain whether he might not be drunk by pinching himself till he fairly yelled. Then, certain, because of the pain, that he was acting and living in waking life, he approached the mirror with diffidence, and once more scanned himself with a sort of inward hope that the nose might by this time be showing as restored. But the result was merely that he recoiled and muttered:

“What an absurd spectacle still!”

Ah, it all passed his understanding! If only a button, or a silver spoon, or a watch, or some such article were gone, rather than that anything had disappeared like this—for no reason, and in his very flat! Eventually, having once more reviewed the circumstances, he reached the final conclusion that he should most nearly hit the truth in supposing Madame Podtochina (wife of the Staff-Officer, of course—the lady who wanted him to become her daughter’s husband) to have been the prime agent in the affair. True, he had always liked dangling in the daughter’s wake, but also he had always fought shy of really coming down to business. Even when the Staff-Officer’s lady had said point blank that she desired him to become her son-in-law he had put her off with his compliments, and replied that the daughter was still too young, and himself due yet to perform five years service, and aged only forty-two. Yes, the truth must be that out of revenge the Staff-Officer’s wife had resolved to ruin him, and hired a band of witches for the purpose, seeing that the nose could not conceivably have been cut off—no one had entered his private room lately, and, after being shaved by Ivan Yakovlevitch on the Wednesday, he had the nose intact, he knew and remembered well, throughout both the rest of the Wednesday and the day following. Also, if the nose had been cut off, pain would have resulted, and also a wound, and the place could not have healed so quickly, and become of the uniformity of a pancake.

Next, the Major made his plans. Either he would sue the Staff-Officer’s lady in legal form or he would pay her a surprise visit, and catch her in a trap. Then the foregoing reflections were cut short by a glimmer showing through the chink of the door—a sign that Ivan had just lit a candle in the hall: and presently Ivan himself appeared, carrying the candle in front of him, and throwing the room into such clear radiance that Kovalev had hastily to snatch up the handkerchief again, and once more cover the place where the nose had been but yesterday, lest the stupid fellow should be led to stand gaping at the monstrosity on his master’s features.

Ivan had just returned to his cupboard when an unfamiliar voice in the hall inquired:

“Is this where Collegiate Assessor Kovalev lives?”

“It is,” Kovalev shouted, leaping to his feet, and flinging wide the door. “Come in, will you?”

Upon which there entered a police-officer of smart exterior, with whiskers neither light nor dark, and cheeks nicely plump. As a matter of fact, he was the police-officer whom Ivan Yakovlevitch had met at the end of the Isaakievsky Bridge.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” he said, “but have you lost your nose?”

“I have—just so.”

“Then the nose is found.”

“What?” For a moment or two joy deprived Major Kovalev of further speech. All that he could do was to stand staring, open-eyed, at the officer’s plump lips and cheeks, and at the tremulant beams which the candlelight kept throwing over them. “Then how did it come about?”

“Well, by the merest chance the nose was found beside a roadway. Already it had entered a stage-coach, and was about to leave for Riga with a passport made out in the name of a certain chinovnik. And, curiously enough, I myself, at first, took it to be a gentleman. Luckily, though, I had my eyeglasses on me. Soon, therefore, I perceived the `gentleman’ to be no more than a nose. Such is my shortness of sight, you know, that even now, though I see you standing there before me, and see that you have a face, I cannot distinguish on that face the nose, the chin, or anything else. My mother-in-law (my wife’s mother) too cannot easily distinguish details.”

Kovalev felt almost beside himself.

“Where is the nose now?” cried he. “Where, I ask? Let me go to it at once.”

“Do not trouble, sir. Knowing how greatly you stand in need of it, I have it with me. It is a curious fact, too, that the chief agent in the affair has been a rascal of a barber who lives on the Vozkresensky Prospekt, and now is sitting at the police station. For long past I had suspected him of drunkenness and theft, and only three days ago he took away from a shop a button-card. Well, you will find your nose to be as before.”

And the officer delved into a pocket, and drew thence the nose, wrapped in paper.

“Yes, that’s the nose all right!” Kovalev shouted. “It’s the nose precisely! Will you join me in a cup of tea?”

“I should have accounted it indeed a pleasure if I had been able, but, unfortunately, I have to go straight on to the penitentiary. Provisions, sir, have risen greatly in price. And living with me I have not only my family, but my mother-in-law (my wife’s mother). Yet the eldest of my children gives me much hope. He is a clever lad. The only thing is that I have not the means for his proper education.”

When the officer was gone the Collegiate Assessor sat plunged in vagueness, plunged in inability to see or to feel, so greatly was he upset with joy. Only after a while did he with care take the thus recovered nose in cupped hands, and again examine it attentively.

“It, undoubtedly. It, precisely,” he said at length. “Yes, and it even has on it the pimple to the left which broke out on me yesterday.”

Sheerly he laughed in his delight.

But nothing lasts long in this world. Even joy grows less lively the next moment. And a moment later, again, it weakens further. And at last it remerges insensibly with the normal mood, even as the ripple from a pebble’s impact becomes remerged with the smooth surface of the water at large. So Kovalev relapsed into thought again. For by now he had realised that even yet the affair was not wholly ended, seeing that, though retrieved, the nose needed to be re-stuck.

“What if it should fail so to stick!”

The bare question thus posed turned the Major pale.

Feeling, somehow, very nervous, he drew the mirror closer to him, lest he should fit the nose awry. His hands were trembling as gently, very carefully he lifted the nose in place. But, oh, horrors, it would not remain in place! He held it to his lips, warmed it with his breath, and again lifted it to the patch between his cheeks—only to find, as before, that it would not retain its position.

“Come, come, fool!” said he. “Stop where you are, I tell you.”

But the nose, obstinately wooden, fell upon the table with a strange sound as of a cork, whilst the Major’s face became convulsed.

“Surely it is not too large now?” he reflected in terror. Yet as often as he raised it towards its proper position the new attempt proved as vain as the last.

Loudly he shouted for Ivan, and sent for a doctor who occupied a flat (a better one than the Major’s) on the first floor. The doctor was a fine-looking man with splendid, coal-black whiskers. Possessed of a healthy, comely wife, he ate some raw apples every morning, and kept his mouth extraordinarily clean—rinsed it out, each morning, for three-quarters of an hour, and polished its teeth with five different sorts of brushes. At once he answered Kovalev’s summons, and, after asking how long ago the calamity had happened, tilted the Major’s chin, and rapped the vacant site with a thumb until at last the Major wrenched his head away, and, in doing so, struck it sharply against the wall behind. This, the doctor said, was nothing; and after advising him to stand a little farther from the wall, and bidding him incline his head to the right, he once more rapped the vacant patch before, after bidding him incline his head to the left, dealing him, with a “Hm!” such a thumb-dig as left the Major standing like a horse which is having its teeth examined.

The doctor, that done, shook his head.

“The thing is not feasible,” he pronounced. “You had better remain as you are rather than go farther and fare worse. Of course, I could stick it on again—I could do that for you in a moment; but at the same time I would assure you that your plight will only become worse as the result.”

“Never mind,” Kovalev replied. “Stick it on again, pray. How can I continue without a nose? Besides, things could not possibly be worse than they are now. At present they are the devil himself. Where can I show this caricature of a face? My circle of acquaintances is a large one: this very night I am due in two houses, for I know a great many people like Madame Chektareva (wife of the State Councillor), Madame Podtochina (wife of the Staff-Officer), and others. Of course, though, I shall have nothing further to do with Madame Podtochina (except through the police) after her present proceedings. Yes,” persuasively he went on, “I beg of you to do me the favour requested. Surely there are means of doing it permanently? Stick it on in any sort of a fashion—at all events so that it will hold fast, even if not becomingly. And then, when risky moments occur, I might even support it gently with my hand, and likewise dance no more—anything to avoid fresh injury through an unguarded movement. For the rest, you may feel assured that I shall show you my gratitude for this visit so far as ever my means will permit.”

“Believe me,” the doctor replied, neither too loudly nor too softly, but just with incisiveness and magnetic “when I say that I never attend patients for money. To do that would be contrary alike to my rules and to my art. When I accept a fee for a visit I accept it only lest I offend through a refusal. Again I say—this time on my honour, as you will not believe my plain word—that, though I could easily re-affix your nose, the proceeding would make things worse, far worse, for you. It would be better for you to trust merely to the action of nature. Wash often in cold water, and I assure you that you will be as healthy without a nose as with one. This nose here I should advise you to put into a jar of spirit: or, better still, to steep in two tablespoonfuls of stale vodka and strong vinegar. Then you will be able to get a good sum for it. Indeed, I myself will take the thing if you consider it of no value.”

“No, no!” shouted the distracted Major. “Not on any account will I sell it. I would rather it were lost again.”

“Oh, I beg your pardon.” And the doctor bowed. “My only idea had been to serve you. What is it you want? Well, you have seen me do what I could.”

And majestically he withdrew. Kovalev, meanwhile, had never once looked at his face. In his distraction he had noticed nothing beyond a pair of snowy cuffs projecting from black sleeves.

He decided, next, that, before lodging a plea next day, he would write and request the Staff-Officer’s lady to restore him his nose without publicity. His letter ran as follows:

DEAR MADAME ALEXANDRA GRIGORIEVNA, I am at a loss to understand your strange conduct. At least, however, you may rest assured that you will benefit nothing by it, and that it will in no way further force me to marry your daughter. Believe me, I am now aware of all the circumstances connected with my nose, and know that you alone have been the prime agent in them. The nose’s sudden disappearance, its subsequent gaddings about, its masqueradings as, firstly, a chinovnik and, secondly, itself—all these have come of witchcraft practised either by you or by adepts in pursuits of a refinement equal to your own. This being so, I consider it my duty herewith to warn you that if the nose should not this very day reassume its correct position, I shall be forced to have resort to the law’s protection and defence. With all respect, I have the honour to remain your very humble servant, PLATON KOVALEV.

“MY DEAR SIR,” wrote the lady in return, “your letter has greatly surprised me, and I will say frankly that I had not expected it, and least of all its unjust reproaches. I assure you that I have never at any time allowed the chinovnik whom you mention to enter my house—either masquerading or as himself. True, I have received calls from Philip Ivanovitch Potanchikov, who, as you know, is seeking my daughter’s hand, and, besides, is a man steady and upright, as well as learned; but never, even so, have I given him reason to hope. You speak, too, of a nose. If that means that I seem to you to have desired to leave you with a nose and nothing else, that is to say, to return you a direct refusal of my daughter’s hand, I am astonished at your words, for, as you cannot but be aware, my inclination is quite otherwise. So now, if still you wish for a formal betrothal to my daughter, I will readily, I do assure you, satisfy your desire, which all along has been, in the most lively manner, my own also. In hopes of that, I remain yours sincerely, ALEXANDRA PODTOCHINA.

“No, no!” Kovalev exclaimed, after reading the missive. “She, at least, is not guilty. Oh, certainly not! No one who had committed such a crime could write such a letter.” The Collegiate Assessor was the more expert in such matters because more than once he had been sent to the Caucasus to institute prosecutions. “Then by what sequence of chances has the affair happened? Only the devil could say!”

His hands fell in bewilderment.

It had not been long before news of the strange occurrence had spread through the capital. And, of course, it received additions with the progress of time. Everyone’s mind was, at that period, bent upon the marvellous. Recently experiments with the action of magnetism had occupied public attention, and the history of the dancing chairs of Koniushennaia Street also was fresh. So no one could wonder when it began to be said that the nose of Collegiate Assessor Kovalev could be seen promenading the Nevski Prospekt at three o’clock, or when a crowd of curious sightseers gathered there. Next, someone declared that the nose, rather, could be beheld at Junker’s store, and the throng which surged thither became so massed as to necessitate a summons to the police. Meanwhile a speculator of highly respectable aspect and whiskers who sold stale cakes at the entrance to a theatre knocked together some stout wooden benches, and invited the curious to stand upon them for eighty kopeks each; whilst a retired colonel who came out early to see the show, and penetrated the crowd only with great difficulty, was disgusted when in the window of the store he beheld, not a nose, but merely an ordinary woollen waistcoat flanked by the selfsame lithograph of a girl pulling up a stocking, whilst a dandy with cutaway waistcoat and receding chin peeped at her from behind a tree, which had hung there for ten years past.

“Dear me!” irritably he exclaimed. “How come people so to excite themselves about stupid, improbable reports?”

Next, word had it that the nose was walking, not on the Nevski Prospekt, but in the Taurida Park, and, in fact, had been in the habit of doing so for a long while past, so that even in the days when Khozrev Mirza had lived near there he had been greatly astonished at the freak of nature. This led students to repair thither from the College of Medicine, and a certain eminent, respected lady to write and ask the Warden of the Park to show her children the phenomenon, and, if possible, add to the demonstration a lesson of edifying and instructive tenor.

Naturally, these events greatly pleased also gentlemen who frequented routs, since those gentlemen wished to entertain the ladies, and their resources had become exhausted. Only a few solid, worthy persons deprecated it all. One such person even said, in his disgust, that comprehend how foolish inventions of the sort could circulate in such an enlightened age he could not—that, in fact, he was surprised that the Government had not turned its attention to the matter. From which utterance it will be seen that the person in question was one of those who would have dragged the Government into anything on earth, including even their daily quarrels with their wives.

Next—

But again events here become enshrouded in mist. What happened after that is unknown to all men._

III

FARCE really does occur in this world, and, sometimes, farce altogether without an element of probability. Thus, the nose which lately had gone about as a State Councillor, and stirred all the city, suddenly reoccupied its proper place (between the two cheeks of Major Kovalev) as though nothing at all had happened. The date was 7 April, and when, that morning, the major awoke as usual, and, as usual, threw a despairing glance at the mirror, he this time, beheld before him, what?—why, the nose again! Instantly he took hold of it. Yes, the nose, the nose precisely! “Aha!” he shouted, and, in his joy, might have executed a trepak about the room in bare feet had not Ivan’s entry suddenly checked him. Then he had himself furnished with materials for washing, washed, and glanced at the mirror again. Oh, the nose was there still! So next he rubbed it vigorously with the towel. Ah, still it was there, the same as ever!

“Look, Ivan,” he said. “Surely there is a pimple on my nose?” But meanwhile he was thinking: “What if he should reply: `You are wrong, sir. Not only is there not a pimple to be seen, but not even a nose’?”

However, all that Ivan said was:

“Not a pimple, sir, that isn’t. The nose is clear all over.”

“Good!” the Major reflected, and snapped his fingers. At the same moment Barber Ivan Yakovlevitch peeped round the door. He did so as timidly as a cat which has just been whipped for stealing cream.

“Tell me first whether your hands are clean?” the Major cried.

“They are, sir.”

“You lie, I’ll be bound.”

“By God, sir, I do not!”

“Then go carefully.”

As soon as Kovalev had seated himself in position Ivan Yakovlevitch vested him in a sheet, and plied brush upon chin and a portion of a cheek until they looked like the blanc mange served on tradesmen’s namedays.

“Ah, you!” Here Ivan Yakovlevitch glanced at the nose. Then he bent his head askew, and contemplated the nose from a position on the flank. “It looks right enough,” finally he commented, but eyed the member for quite a little while longer before carefully, so gently as almost to pass the imagination, he lifted two fingers towards it, in order to grasp its tip—such always being his procedure.

“Come, come! Do mind!” came in a shout from Kovalev. Ivan Yakovlevitch let fall his hands, and stood disconcerted, dismayed as he had never been before. But at last he started scratching the razor lightly under the chin, and, despite the unhandiness and difficulty of shaving in that quarter without also grasping the organ of smell, contrived, with the aid of a thumb planted firmly upon the cheek and the lower gum, to overcome all obstacles, and bring the shave to a finish.

Everything thus ready, Kovalev dressed, called a cab, and set out for the restaurant. He had not crossed the threshold before he shouted: “Waiter! A cup of chocolate!” Then he sought a mirror, and looked at himself. The nose was still in place! He turned round in cheerful mood, and, with eves contracted slightly, bestowed a bold, satirical scrutiny upon two military men, one of the noses on whom was no larger than a waistcoat button. Next, he sought the chancery of the department where he was agitating to obtain a Vice-Governorship (or, failing that, an Administratorship), and, whilst passing through the reception vestibule, again surveyed himself in a mirror. As much in place as ever the nose was!

Next, he went to call upon a brother Collegiate Assessor, a brother “Major.” This colleague of his was a great satirist, but Kovalev always met his quarrelsome remarks merely with: “Ah, you! I know you, and know what a wag you are.”

Whilst proceeding thither he reflected:

“At least, if the Major doesn’t burst into laughter on seeing me, I shall know for certain that all is in order again.”

And this turned out to be so, for the colleague said nothing at all on the subject.

“Splendid, damn it all!” was Kovalev’s inward comment.

In the street, on leaving the colleague’s, he met Madame Podtochina, and also Madame Podtochina’s daughter. Bowing to them, he was received with nothing but joyous exclamations. Clearly all had been fancy, no harm had been done. So not only did he talk quite a while to the ladies, but he took special care, as he did so, to produce his snuffbox, and deliberately plug his nose at both entrances. Meanwhile inwardly he said:

“There now, good ladies! There now, you couple of hens! I’m not going to marry the daughter, though. All this is just—par amour, allow me.”

And from that time onwards Major Kovalev gadded about the same as before. He walked on the Nevski Prospekt, and he visited theatres, and he showed himself everywhere. And always the nose accompanied him the same as before, and evinced no signs of again purposing a departure. Great was his good humour, replete was he with smiles, intent was he upon pursuit of fair ladies. Once, it was noted, he even halted before a counter of the Gostini Dvor, and there purchased the riband of an order. Why precisely he did so is not known, for of no order was he a knight.

To think of such an affair happening in this our vast empire’s northern capital! Yet general opinion decided that the affair had about it much of the improbable. Leaving out of the question the nose’s strange, unnatural removal, and its subsequent appearance as a State Councillor, how came Kovalev not to know that one ought not to advertise for a nose through a newspaper? Not that I say this because I consider newspaper charges for announcements excessive. No, that is nothing, and I do not belong to the number of the mean. I say it because such a proceeding would have been gauche, derogatory, not the thing. And how came the nose into the baked roll? And what of Ivan Yakovlevitch? Oh, I cannot understand these points—absolutely I cannot. And the strangest, most unintelligible fact of all is that authors actually can select such occurrences for their subject! I confess this too to pass my comprehension, to—But no; I will say just that I do not understand it. In the first place, a course of the sort never benefits the country. And in the second place—in the second place, a course of the sort never benefits anything at all. I cannot divine the use of it.

Yet, even considering these things; even conceding this, that, and the other (for where are not incongruities found at times?) there may have, after all, been something in the affair. For no matter what folk say to the contrary, such affairs do happen in this world—rarely of course, yet none the less really.

Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol (1809-1852) was a Russian novelist, humorist, and dramatist, writing with an eye toward realism and sometimes magic realism. His works often satirized Russian society and government. “The Nose” and “The Overcoat” are two of his most well-known and acclaimed works.

Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol (1809-1852) was a Russian novelist, humorist, and dramatist, writing with an eye toward realism and sometimes magic realism. His works often satirized Russian society and government. “The Nose” and “The Overcoat” are two of his most well-known and acclaimed works.

Story reprinted under public domain licensing agreement and with thanks to Project Gutenberg Australia.

Comments are closed.