In the middle of a downtown street, a woman wearing red forms a focus — an apex — in a picture of shifting motion, a crowd moving, other buildings overlaid on the original scene. But the woman is constant, her red outfit standing out. Seeing with the camera lens has freed photographer Harry Callahan, opened him to what the human eye has been conditioned not to see — the multiplicity of life, the layers and levels of reality, from the everyday to the non-ordinary.

With a wide-angle lens (Callahan frequently uses double or even triple exposures), he expands the scene, extends its limits, and creates new relationships between objects. In a photo shot “straight” — without the collage/montage effect of super-imposed images — of a beach scene, individuals in the water and on shore take on a new vulnerability. Reduced in size and stripped of their human superiority, we now see them more as part of nature than apart, dwarfed in relationship to the ocean’s vastness and surrounding sand. They are caught in a new light, between our expectations of human importance and a world where size, power, and status mean little.

In contrast, the artist Jill Giegerich combines collage, painting, and relief in her work. She introduces objects like wooden table legs that are the things themselves, and they also become something else in relationship to the new context. The surfaces she uses are not the usual rectangles or squares. Instead, they follow the curves and angles of the contents, the shapes not just a frame but part of the art itself. Within the plane of a piece, Giegerich creates illusions of different depths and dimensions all happening simultaneously, giving a disquieting effect.

In photography, the camera lens “sees” something via the artist (or vice versa), records what it sees and frames it. The camera is the grammar, the organizing principal that allows the artist’s perceptions to be communicated to others.

In painting, the colors have meaning apart from the subject. They aren’t dependent on an image to communicate emotions, ideas. They have been freed to become, to enter the in-between world that Paul Klee refers to in the following passage, an excerpt from his writing that I saw at SFMOMA:

In our time worlds have opened up which not everybody can see into, although they too are part of nature….An in-between world…. I call it that because I feel that it exists between the worlds our senses can perceive, and I absorb it inwardly to the extent that I can project it outwardly in symbolic correspondences. Children, madmen, and savages can still, or again, look into it. And what they see and picture is for me the most precious kind of confirmation. For we all see the same things but from different angles.

The artist’s lexicon is the palate, and nothing limits the range of colors/emotions that can be produced on a canvas. How colors react to each other and make new colors when mixed are the criteria. No longer does blue represent sky or water; it can become something new. Greens, too, may leap out of their assumed connection with nature and express something different.

While we don’t let go entirely of the usual associations — and couldn’t if we wanted to because they often are archetypal (images and patterns that repeat themselves throughout history) — we can entertain other possibilities. A sky can be green instead of blue; a lake can be red; a human purple. All of these colors, then, express a different perception of the thing perceived and strike the viewer freshly — come in a side door and catch us off guard: trigger an emotional response that lifts us into a new awareness of ourselves and the environment.

By contrast, in writing, we are dependent on words and their multiple meanings to convey either a single idea or to suggest many interpretations. But words don’t come directly from the head of Zeus. Instead they travel through the entire human social body, from the beginning of time, on the way picking up nuances, cultural inflections, meanings associated with a particular era: in short, they have baggage that both enriches and restricts, enhances and confuses. And that baggage continues to resonate today, just as our ancestor’s idiosyncratic behavior and histories can plague later generations.

The word “nice” illustrates my meaning. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and as late as 1587, nice meant wanton, loose-mannered, and lascivious. Other meanings accrued to nice during that period, including foolish, stupid, senseless, strange, rare, uncommon, slothful, and lazy. By the end of the sixteenth century, and on into the seventeenth, nice began to take on some of its current characteristics: nice meant to be coy, shy, modest, reserved, tactful, fastidious, dainty, and so on. Today — well, to be nice is not necessarily nice…it has become a bland, overly used word with an imprecise meaning.

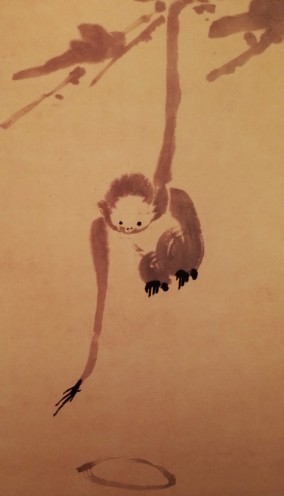

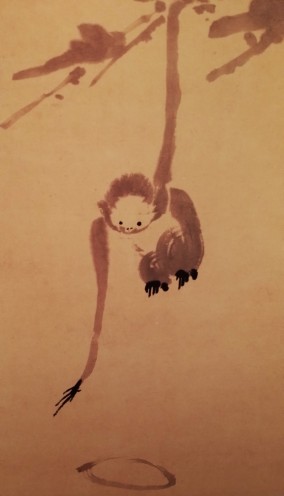

The other difficulty (or freedom) of language are the rules that accompany it. While singular words have resonance, it takes a string of words, linked together by agreed-on syntax and grammar, to evoke larger meanings, complex thoughts. Ape gives me only a fuzzy picture of an ape, my personal image of ape. Ape loping causes me to see the animal in action. Ape loping towards me sets me in motion, too.

But for more experimental writers — ones who want to explore the “in-between world,” less satisfied with experiencing the conventional usage of words in a sentence — the opposite (or a variation) of the usual pattern prevails. Experimental writers deliberately shake up syntax, test what happens when adjectives are used as verbs, when prepositions don’t take objects, when thoughts are left incomplete. They will join together words in dense paragraphs without punctuation in order to break down our expectations of linear thought, or isolate words we normally don’t pay attention to.

Leslie Scalapino and Claude Royet Journoud are two poets who come to mind. Often they isolate a single word on a line or page, causing the word — ”that,” perhaps, or “it” — to shift its role, step out of the persona of a pronoun referring to something else, or a preposition making connections with the subject of the sentence and its object, to taking on substantiality in its own right. Isolated on a line or page, each letter in the word has weight and calls attention to itself, just as each letter in the original alphabet actually resembled something, was a thing in itself. It had a self. It selfed. It i/t. It was an I making a crossing or being crossed. The word becomes a character — its letters characters — in the theater of the page.

Not that there’s anything wrong with our usual way of perceiving through language and its rules: many complex, mysterious things can be conveyed in traditional ways. But as Orwell pointed out in his essay “Politics and the English Language,” clichés and unoriginal images prevent us from being discerning and distort rather than reveal. So, too, can our usual ways of speaking and writing prevent us from experiencing a multi-dimensional, fragmented, chaotic, bizarre, inexpressible reality, often with an organizing center that may be different from what we expect.

A poem that illustrates these dynamics and also investigates Klee’s in-between world is one by Kathleen Fraser from Something (even human voices) in the foreground, a lake.

THEY DID NOT MAKE CONVERSATION

A lake as big, the early evening wind at the bather’s neck. Something pulling (or was it rising up) green from the bottom. You could lie flat and let go of the white creases. You could indulge your fear of drowning in the arms of shallow wet miles. You did not open your mouth, yet water poured into openings, making you part. Bone in the throat. That dark blue fading, thinning at the edges . On deck chairs with bits of flowered cloth across their genitals, the guests called out in three languages and sometimes pointed, commenting on the simple beauty of bought connection. The swan-like whiteness of the day. That neck of waves. There was always a tray with small red bottles. And pin-pointed attentions, at each slung ease (2).

I can’t do a full explication of the poem within this essay, so I will discuss only enough to illustrate my point. But I do want to show that the writer accomplishes here something that she articulates in the flyleaf to her book, Notes preceding trust: “I wish, in my work, to resist habit (mine and others’), to uncover something fresh that connects with the reader in a way she or he could not have predicted. An ache, a splash of cold water, a recognition.”

In the poem’s opening, we are presented with “a lake as big.” The immediate impulse is to ask “as big as what?” But if we resist that impulse, we soon discover the comparison is more powerful by having it open-ended. Our imagination fills in the blank, forcing us into our own interiors, our own in-between worlds. Another reading would be to compare the lake to the early evening wind, extending the comparison to something invisible but tangible. This lake, then, isn’t an actual lake. It takes on mythic, magical proportions — suggesting perhaps the waters of the unconscious, unfathomable and illimitable.

In the next group of words, the speaker questions her own perceptions of “something pulling…green from the bottom.” There are various ways to read this phrase. Either we can see it as something actually pulling the color green from the bottom, bringing it into view, perhaps the bather. Or we can hear it as something green — fresh, new, living — pulling (rising up) from the bottom on its own.

Then the reader is brought in, the first complete sentence, the previous phrases like the breath that precedes a spoken thought, rising up green from the bottom. We are part of the poem’s setting. It’s now possible to let go of the “white creases,” which could be the lighter indentations left in folds of skin when we are out in the sun for a long time, those vulnerable spots hidden from glaring rays. But they also could be the crease in a page, perhaps where a book folds at its center. Maybe the “you” is a book/page — or, put another way, you are compared to a book/page — that can open up, let go, “indulge your fear of drowning in the arms of shallow wet miles.”

And we do fear drowning, especially in shallow water. What could be more humiliating than to drown in water that isn’t over our heads? Yet our fears often are just as groundless. However, the provocative part of this image is the “wet miles.” Again, we don’t know what the miles encompass, again giving the image more suggestiveness. The ambiguity causes our hidden fears of the unknown to surface, and we imagine an endless expanse of miles, wet now from the lake that the poem started with.

As the title suggests, this poem is about our inability to communicate and connect with others, except at times via “bought connection.” Fraser accomplishes what she hopes to do: she creates an ache, a splash of recognition. She takes me into that bleak landscape, the frightening dimension that’s always present in human relations but rarely alluded to.

Just as the visual artist’s purpose — one of them, at least — is to help us see beyond the accepted meanings, to shake up our perceptions, so writers, too, use their colors/words in new, unexpected ways. As Poet Elaine Equi says in Mirage #3 (The Women’s Issue),

Experimental when it refers to literature is usually connected with the idea of avant-garde and/or the act of challenging traditional forms. To be an experimental writer implies rebellion, but I prefer to give the idea of experimentation its scientific connotation which is closer to a method of discovery (75).

As with the visual artists I’ve mentioned here, innovative writing stretches our perceptions, shows us things — even turns certain words into objects — in new, unexpected relationships, causes us to stop, to look. In doing so, we have expanded our vision — discovered that “these things aren’t fancies, but facts” (Klee).

Lily Iona MacKenzie teaches writing at the University of San Francisco. Her essays, poetry, book reviews, interviews, and short fiction have found a home in numerous publications. All This, a poetry collection, was published in October 2011. Fling, one of her novels, will be published in July 2015. A recent issue of Notes Magazine featured her as the spotlight author, showcasing her poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. All of the arts inspire her, and she dabbles in painting and collage when she isn’t writing.

http://lilyionamackenzie.wordpress.com/