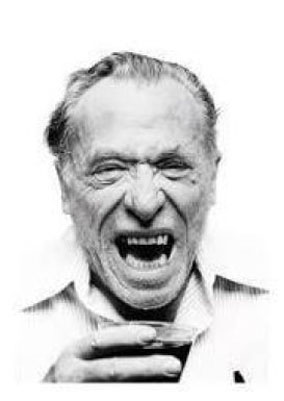

Steve Almond

“…funny and beguiling and completely original.” — Lorrie Moore

Steve Almond is the author of My Life in Heavy Metal (Atlantic/Grove, 2002), The New York Times bestseller, Candyfreak (Algonquin Books, 2005), and God Bless America (Lookout Press, 2011). His short fiction and essays can be found in The New York Times Magazine, GQ, The Wall Street Journal, Tin House, Playboy, Zoetrope, and Ploughshares. “Donkey Greedy, Donkey Gets Punched” was selected for the Best American Short Stories 2010 and has been optioned for film by Spilt Milk Entertainment. He regularly teaches at Grub Street in Boston and the Tin House Writer’s Conference. In 2011 he was the keynote speaker at Conversations & Connections, Washington D.C., held at The Johns Hopkins University D.C. campus. We want to thank Mr. Almond for taking time to be our Fall 2012 Centerfold and talk with our Editor in Chief, Rae Bryant, on the crafts of storytelling and spanking.

We had no idea you had a thing for spanking. How did you begin with paddle spanking? So David Bowie sexy.

We had no idea you had a thing for spanking. How did you begin with paddle spanking? So David Bowie sexy.

SA: I don’t spank and tell. At least not until there’s money on the table.

Do you have other fetishes of which your readers are not aware?

SA: Yeah, but I don’t think of them as “fetishes.” I think of them as “future marketing opportunities.”

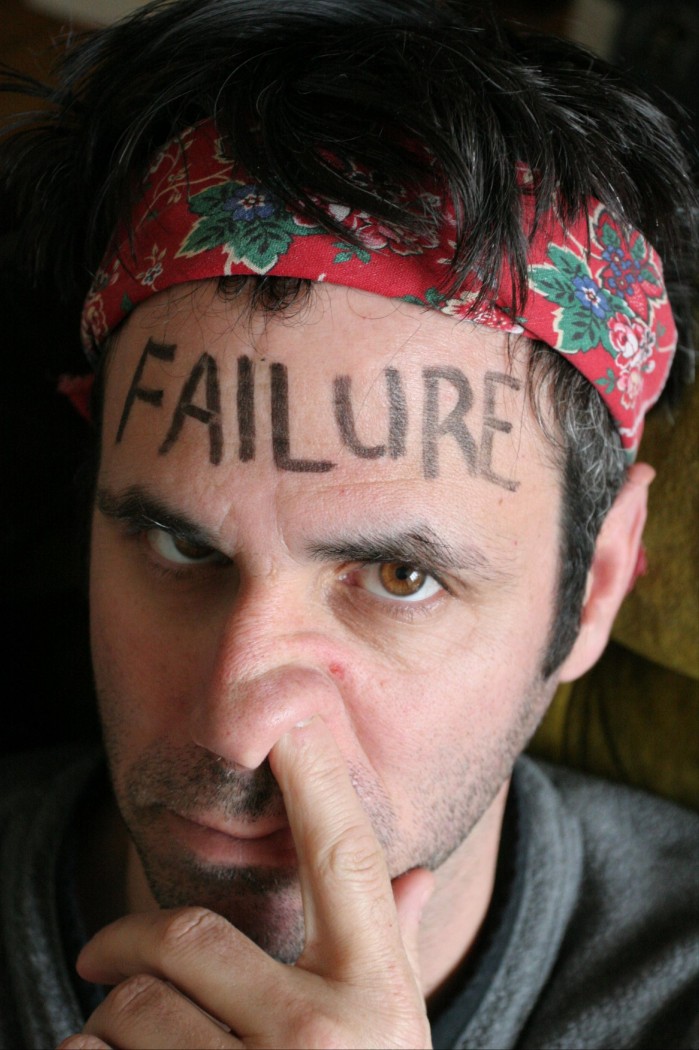

Writers generally learn to accept failure and rejection as a necessary evil to our craft; however, you seem to have embraced it and taken it to an artistic level. Tell us how you came to this practice of failure and nose-picking Zen.

SA: I guess I just took a long, hard look at my talents and decided that betting on failure was in my own self-interest. It was odd at first, having to wish for rejections. But at a certain point something just clicks, and you see that little envelope and tear it open and there’s this little passive aggressive form letter telling you how much you suck and rather than getting all defensive and grief stricken, you realize, Hey, whoever sent this is right. I do suck. Rather than fighting the pain, you lean into it. It’s like getting spanked in that way, I guess.

In your collections title story, “God Bless America,” protagonist, Billy Clamm, seems to more than “lean into” this sense of defeat, but rather embrace his stage actor dream turned Boston tour guide reality:

In your collections title story, “God Bless America,” protagonist, Billy Clamm, seems to more than “lean into” this sense of defeat, but rather embrace his stage actor dream turned Boston tour guide reality:

It was a pity that so much of the country was now run based on convenience. Or, more than that, it was really ironical. But now that Billy had hitched his wagon to the right dream, he felt much more connected to history, much more like a pioneer, though he was just starting out on his long journey west, and might someday starve and even be forced to eat another person, not literally, but metaphorically. He hoped he would never have to eat another person metaphorically. At the same time, he was aware of that possibility. (8)

How hopeful would Billy Clamm be of the recent and current political and economic failures/climates?

SA: Actually, Billy Clamm is pretty much a walking example of the “independent voter” they round up for those post-debate panels: he doesn’t think with his brain. He thinks with his heart. This is a virtue when it comes to romantic comedies, but it’s not a very smart way to elect a President. Billy Clamm is, like most Americans, a decent, hopeful guy. But he’s also incredibly wounded and gullible. And that’s what the worst candidates prey upon. They’re salesman who seduce guys like Billy without actually caring about them.

SA: Actually, Billy Clamm is pretty much a walking example of the “independent voter” they round up for those post-debate panels: he doesn’t think with his brain. He thinks with his heart. This is a virtue when it comes to romantic comedies, but it’s not a very smart way to elect a President. Billy Clamm is, like most Americans, a decent, hopeful guy. But he’s also incredibly wounded and gullible. And that’s what the worst candidates prey upon. They’re salesman who seduce guys like Billy without actually caring about them.

Your fiction and nonfiction delve into socio-political topics of national and diverse interest, sometimes with personal intentions and consequences, namely your take this job and shove it up Condoleezza Rice’s ass essay. Where do you lie on the fiction versus nonfiction debate? Is all fiction really nonfiction? All nonfiction really fiction?

SA: People try to complicate the fiction/non-fiction debate, usually because they want an excuse for lying to people. It’s not complicated. Non-fiction is a radically subjective version of events that objectively took place. Period. Any time you consciously make up stuff — without telling readers — you’re making fiction. Which is fine, great, blessed. Just be honest about it.

SA: People try to complicate the fiction/non-fiction debate, usually because they want an excuse for lying to people. It’s not complicated. Non-fiction is a radically subjective version of events that objectively took place. Period. Any time you consciously make up stuff — without telling readers — you’re making fiction. Which is fine, great, blessed. Just be honest about it.

What upcoming projects do you have that you’d like your readers to know about?

SA: I’m hoping to put out more DIY books, a series of six little books of dirty stories.

You can read more about Steve Almond and his works at stevealmondjoy.com, and you can buy a copy of God Bless America at the following locations:

IndieBound (Your local bookseller)

Powell’sAmazon.com (USA)

Amazon.ca (Canada)

Amazon.co.uk (UK)

Barnes & Noble

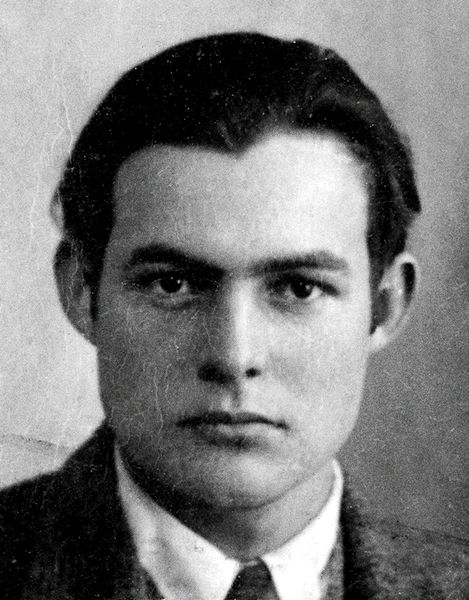

Biography | Ernest Hemingway

ERNEST MILLER “PAPA” HEMINGWAY

ERNEST MILLER “PAPA” HEMINGWAY

Born: July 21,1899, Oak Park, Illinois

Died: July 2, 1961, Ketchum, Idaho — Suicide

Ernest “Papa” Hemingway is the expatriate writer we love to hate and hate to love. He is the superhero/antihero equivalent of literary greatness with a Royal Quiet de Luxeon at his hip and a bottle of “grog” in his hand, shirt ripped open for the world to see his big, manly, hairy chest. Journalist, world traveler, fighter, marrying man, decorated WWI Italian army volunteer, sportsman, fisherman, big game hunter, Hemingway’s bravado made him infamous and a fine dinner guest. His contributions to the community of letters is unattested, bringing an understatement and simplicity of style to the modernist canon like none before him. John Updike and Joan Didion, and many more, claim him as a major inspiration. As likely to carry a urinal home from Sloppy Joe’s, his Key West bar hangout, as he was to write major literary works, Hemingway, the man, was sometimes larger than his work and made him the media eye candy of his time.

When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning as soon after first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write. You read what you have written and, as you always stop when you know what is going to happen next, you go on from there. You write until you come to a place where you still have your juice and know what will happen next and you stop and try to live through until the next day when you hit it again. You have started at six in the morning, say, and may go on until noon or be through before that. When you stop you are as empty, and at the same time never empty but filling, as when you have made love to someone you love. Nothing can hurt you, nothing can happen, nothing means anything until the next day when you do it again. It is the wait until the next day that is hard to get through.

— Ernest Hemingway, The Art of Fiction No. 21, The Paris Review

A Conversation with George Plimpton in a Madrid Café, 1954

Hemingway is arguably the patriarch of the Paris expatriates with Gertrude Stein his matriarch and F. Scott Fitzgerald his chum. Rest in Peace, Papa.

HEMINGWAY’S FIGHTS

Hemingway vs. Wallace Stevens (1936) Street fight, Key West, Florida

Hemingway vs. Max Eastman (1938) Max Perkins’ Office, Scribner’s, New York, New York

HEMINGWAY’S FAVORITE BARS

Sloppy Joe’s — Key West, Florida

Floridita Bar, San Francisco, Cuba

Dôme, Paris, France

HEMINGWAY’S WIVES

Elizabeth Hadley Richardson (1891 — 1979)

- Married 1921

- Divorced 1926

Pauline Marie Pfeiffer (1895 — 1951)

- Married 1927

- Divorced 1940

Martha Ellis Gellhorn (1908 — 1998)

- Married 1940

- Divorced 1945

Mary Welsh Hemingway (1908 — 1986)

- Married 1946

- Widow

HEMINGWAY’S NOTABLE WORKS

“Indian Camp” (1924, Transatlantic Review)

In Our Time (1925, collection)

The Sun Also Rises (1926)

Death in the Afternoon (???)

“Hills Like White Elephants” (1927)

Men Without Women (1927)

A Farewell to Arms (1929)

“The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” (1935)

“The Snows of Kilimanjaro” (1936, Esquire)

The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories (1938)

For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940)

Across the River and into the Trees (1950)

The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

A Moveable Feast (1964)

Islands in the Stream (1970)

True at First Light (1999)

More Books…

HEMINGWAY’S AWARDS

The Pulitzer Prize in Fiction (Finalist, 1941) For Whom the Bell Tolls

The Pulitzer Prize in Fiction (1953) The Old Man and the Sea

The Nobel Prize in Literature (1954)

SOURCES

Heller, Nathan. “Hemingway: How the Great Novelist Became the Literary Equivalent of the Nike Swoosh.” Slate Magazine. March 16, 2012.

Lost Generation. “Ernest Hemingway Biography.” n.d.

Nobel Lectures. Literature 1901-1967, Editor Horst Frenz, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1969.

Plimpton, George. “Ernest Hemingway: The Art of Fiction No. 21.” The Paris Review. May 1954. n.d.

Rich, Frank K. “Hemingway.” Modern Drunkard Magazine. n.d.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

www.pen-ne.org/news-noteworthy/penhemingway-award