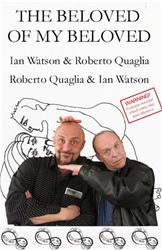

Ian Watson wrote the screen story for Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence, based on almost a year’s work with Stanley Kubrick. His most recent books are The Beloved of My Beloved, a volume of transgressive and funny stories in collaboration with Italian surrealist Roberto Quaglia, perhaps the only full-length genre fiction by two authors with different mother tongues (a story from which, “The Beloved Time of Their Lives,” won the British Science Fiction Association Award for short fiction, Easter 2010), and the erotic satire Orgasmachine, first begun almost 40 years ago but only available until now in Japanese; both from NewCon Press. Read more at Ian Watson.

“I usually write in order to have a transformative impact on people’s minds as well as to entertain…”

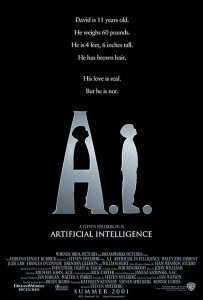

MMR: Could you speak a little on your experiences with A.I. Artifical Intelligence and working with Stanley Kubrick and Stephen Spielberg?

IW: In fact I only worked with Stanley himself (for about 9 months, with a couple of subsequent short recalls about a year apart). After Stanley died, Spielberg went through the existing material, including not only my screen story but all the scenes I’d written for Stanley from which I finally extracted the screen story—and these included stuff which Stanley had instructed me not to put in the screen story, perhaps principally the Flesh Fair (the violent carnival of destruction of robots), of which I’d done several versions and which fortunately Spielberg restored to the story. Another important thing which Spielberg did was to restore my Gigolo Joe to full eloquence again. Stanley forever insisted that Joe and other robots should talk very simply, rather like Peter Sellars in Being There; so, if my Joe started to sound too bright or witty, Stanley would slap this down.

After Stanley died, Spielberg went through the existing material, including not only my screen story but all the scenes I’d written for Stanley from which I finally extracted the screen story—and these included stuff which Stanley had instructed me not to put in the screen story, perhaps principally the Flesh Fair (the violent carnival of destruction of robots), of which I’d done several versions and which fortunately Spielberg restored to the story. Another important thing which Spielberg did was to restore my Gigolo Joe to full eloquence again. Stanley forever insisted that Joe and other robots should talk very simply, rather like Peter Sellars in Being There; so, if my Joe started to sound too bright or witty, Stanley would slap this down.

Spielberg never actually communicated with me at all because there was no reason to. With A.I. he was writing his first SF screenplay since E.T., based on my material, and I think he may have hoped for an Oscar nomination, although this never happened. Worldwide, A.I. was very successful (and the 4th highest earner of the year) but it didn’t do quite so well in America, because the film, so I’m told, was too poetical and intellectual in general for American tastes. Plus, quite a few critics in America misunderstood the film, thinking for instance that the Giacometti-style beings in the final 20 minutes were aliens (whereas they were robots of the future who had evolved themselves from the robots in the earlier part of the film) and also thinking that the final 20 minutes were a sentimental addition by Spielberg, whereas those scenes were exactly what I wrote for Stanley and exactly what he wanted, filmed faithfully by Spielberg. As for sentimentality, the ending is in fact very bleak. After one perfect day with his recreated mother, the little robot boy will never ever see her again no matter how long he exists. Stanley hoped during his life that Spielberg might direct A.I. because he wanted the film to be a scientific fairy tale, and Spielberg has the fairy tale touch, but authentic fairy tales may have tragic endings rather than happy-ever-after. No happy-ever-after here! Alone-ever-after, on the contrary.

Last Autumn (2009) a large and sumptuous book about the project was published by Thames & Hudson, A.I. Artificial Intelligence From Stanley Kubrick to Steven Spielberg: The Vision Behind the Film (edited by Jan Harlan & Jane Struthers), containing a lot of concept drawings by Chris Baker (Fangorn) and photos of some of the pages I wrote for Stanley, and quotes from my screen story.

The circumstances of working with Stanley were so idiosyncratic and one-off—a bit like being struck by lightning—that they hardly yield a usable moral for other writers, although in the aftermath of A.I. I do have one spot of advice: Beware of plausible and pleasant directors with a pet project who claim to have everything lined up but who are either romancing or lying (the distinction being unclear to their brains) if they ask a writer to do work on spec, without paying for it, at least in part, up front. I’ve learned this in the past ten years at the cost of some wasted time now and then.

MMR: You’re a poet, too, eh? A multi-tasking writer, novelist, screenwriter extraordinaire? Do you have a preferred medium? Do you find yourself floating between them depending upon the season? A true love?

IW: I think ultimately I prefer short stories. Right now I can find no motivation to write another novel. My most recent novel, Mockymen (2003, after about 4 years of hard fight to get it published anywhere) may be, I think, my best novel, but it had quite a limited number of readers, few of them in my own country, whereas my stories are rather more widely read, and I usually write in order to have a transformative impact on people’s minds as well as to entertain, a purpose not served if I don’t get enough readers. I’ll write a poem whenever an idea fits poetry better than prose, not least because in a story you have more circumstances to rationalise (and most of all in a novel).

MMR: You and Mike Allen collaborated on the writing of “They Say That Time Assuages.” Seems that you wear collaboration well. What most draws you to working with other creatives on projects?

IW: Synergy. But you have to be very much in tune with the collaborator. With the Italian surrealist Roberto Quaglia I produced a complete volume of bizarre transgressive linked stories, The Beloved of My Beloved (NewCon Press, UK, 2009), almost as if we shared the same brain. This is probably the only full-length genre fiction by two authors with different mother tongues. One of the stories (one of the tamest!) has just won the British Science Fiction Association Award for Best Short Fiction of last year. Incidentally, it’s 33 years since I last won a BSFA Award; so there may be a moral there. Two other component tales were reprinted in The Mammoth Book(s) of Best New Erotica. Recently Roberto and I collaborated on an SF film treatment for an Italian director who did pay us up front.

IW: Synergy. But you have to be very much in tune with the collaborator. With the Italian surrealist Roberto Quaglia I produced a complete volume of bizarre transgressive linked stories, The Beloved of My Beloved (NewCon Press, UK, 2009), almost as if we shared the same brain. This is probably the only full-length genre fiction by two authors with different mother tongues. One of the stories (one of the tamest!) has just won the British Science Fiction Association Award for Best Short Fiction of last year. Incidentally, it’s 33 years since I last won a BSFA Award; so there may be a moral there. Two other component tales were reprinted in The Mammoth Book(s) of Best New Erotica. Recently Roberto and I collaborated on an SF film treatment for an Italian director who did pay us up front.

MMR: What’s in the works for Ian Watson? Upcoming projects? Readings? Films? Books/collections?

IW: I also co-run SF conventions, so Newcon5 is upcoming in October 2010, the only convention held in a Fishmarket (admittedly converted into an arts lab) if any readers of this happen to be near Northampton UK at the time. I’ve enormously enjoyed going to conventions run by other people, so I like to put something back into the community. And I preside over the Northampton SF Writers Workshop which has even given rise to a publisher, namely Ian Whates’ fast expanding NewCon Press, one of its most recent products being the first ever publication in English of my Japanese-influenced erotic satire Orgasmachine. Beautifully produced books!

I’m still trying to get an agent or publisher for an ambitious novel about the Black Death (which was not bubonic plague) co-written over the course of two years with Andy West, another member of the NSFWG, set in medieval Syria, Iran and Ethiopia, and in the very near future in America, Europe and the Middle East. Actually I’ve never used an agent before, simply doing the job myself, but this book is a different kettle of fish. Always try to do something new! I’m off to the Semana Negra cultural fiesta in the north of Spain in July (I’ve been teaching myself Spanish for a few years), so I’m hoping that the Icelandic volcano calms down or that winds blow from the south at the time, and to Sicily and Rome in September so that one of my Italian publishers can publicise his edition of my Gardens of Delight set in the ‘domain’ of Hieronymus Bosch.

Oh, and Games Workshop have finally relented and un-banned my Warhammer 40K novel Space Marine which people were paying a lot for tattered copies of on eBay, and whilst they won’t allow it in their own shops in case it confuses their younger clientele it’s now available as print on demand, and apparently copies are flying forth. My decade-long campaign of Chinese water torture (drip drip drip of humour and patience) finally succeeded. Never lose one’s temper with publishers!