Pretty is something you’re born with.

But beautiful, that’s an equal opportunity adjective.

Author unknown

The ancient Greek philosophers spoke at length about beauty. Plato said, “The three wishes of every man are to be healthy, to be rich by honest means, and to be beautiful.” Asked why people desire physical beauty, Aristotle said, “No one that is not blind could ask that question.”[i] Beauty has traditionally been considered an innate human value. Beauty discriminates. Beauty is diverse. Beauty matters. Beauty is the topic of this column.

One beautiful aspect of writing body narrative is visibility on the page and ultimate acceptance of our messy wholeness. Our physical beauty, the body, writing, and acceptance of ourselves are all interconnected.

I want to know if you can see beauty, even when it is not pretty, every day,

and if you can source your own life from its presence.[ii]

– Oriah Mountain Dreamer

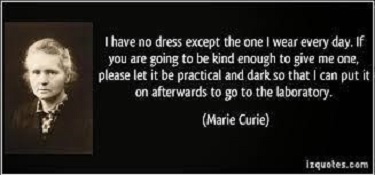

According to Nancy Etcoff, Harvard Medical School psychologist, practicing psychologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, and author of Survival of the Prettiest: The Science of Beauty, “beauty is a universal part of human experience. It evokes pleasure, rivets attention, and impels actions….”[iii] In the book, she discerns similarities in the ways humans across cultures perceive and respond to beauty. According to a Publisher’s Weekly editorial review, the most important message in this book is that we cannot ignore our evolutionary past when attempting to accept the current norms of beauty.

Socially accepted beauty is like socially accepted final drafts. In first drafts, the beauty is there, but we don’t see it until the piece is polished. Similarly, there is an inner beauty to all of us, even if society doesn’t recognize it. Regardless of outer/published beauty, we need to recognize our ‘messy’ beauty and honor it. It is, after all, the core part of our “outer beauty.”

The media frequently presents the “normal” body as free from fat, wrinkles, physical disabilities, and deformities. This narrow representation led to what is considered a marker of normalcy—which consists of unrealistic expectations. This ultimately leads to dissatisfaction with our bodies. The objectification of beauty in the media reveals a possible neglect of women’s internal beauty.[iv] This, too, is true in writing too. We only see polished writing in most publications, which leads us to a similar disconnect, neglect, and devaluing of the messy writing process.

According to Harris Sockel, author of ebook We Will Never Know What’s Inside Our Bodies, “Writers are at their ugliest when they’re doing their best writing” He also says, “You need to start from ugliness to do this well. Something to fight against. Something to try to change…”[v] Is it possible that the hegemony of beauty prevents us from doing our best (and paradoxically ugliest) writing? Maybe it’s that the obsession with beauty prevents us from trying/failing/trying again. Samuel Beckett said, “the goal is to fail better,” something that’s hard to do if we’re constantly obsessing about perfecting our writing and not allowing ourselves to produce the icky in-between drafts, or “shitty first drafts” as Anne Lamott refers to them.

Don’t hesitate to write a messy first draft, even if it feels ugly. You may stir up something in you that is being seen for the first time or is a work-in-progress. Follow your intuition with what is beautiful. We might love a sentence that others hate, but we should continue to believe in that sentence because we know what it can do. Love the parts of your body the media might say are ugly—you know the strength in them that others may not see. Addressing the ugly parts of your body and embracing the ugly parts of writing as well may be challenging but it may also be liberating and help offer hope for healing.

The bottom line is that I like my first drafts to be blind, unconscious, messy efforts; that’s what gets me the best material .

–Jennifer Egan

Certain people can walk into a room and be noticed immediately. They appear to have an air of confidence, a magnetic quality about them. The same can be said for carefully thought-out characters in our writing.

People who live in a sensually alive body and live with a compassionate and loving heart and peaceful mind are seemingly bold and beautiful. Being sensually alive in the body is about being okay with our flaws and imperfections. It’s about finding sexiness in what is unique and even broken. If we are only showing our perfect drafts to others, perhaps we are not actually experiencing the ecstasy that comes when we can accept ourselves just the way we are.

Exuberance is Beauty.

— William Blake

Describe a time you were comfortable in your own skin, immersed yourself in the world, inspired others with your words, felt beautiful, passed along a magical spark.

No matter how plain a woman may be, if truth and honesty are written across her face, she will be beautiful.

– Eleanor Roosevelt

Henry James met the English novelist George Eliot when she was 49 years old. “She is magnificently ugly,” he wrote to his father. “She has a low forehead, a dull grey eye, a vast pendulous nose, a huge mouth, full of uneven teeth…Now in this vast ugliness resides a most powerful beauty which, in a very few minutes, steals forth and charms the mind, so that you end as I ended, in falling in love with her…Perhaps we are truly human when we come to believe that beauty is not so much in the eye, as in the heart, of the beholder.”[vi]

Embrace strangeness and unconventional beauty in your writing. Celebrate it. Part of the writing process is learning to trust your imagination, quirkiness, fetishes, and complexities. Writing about your body can help you feel and see in new ways—to discover your writing and, ultimately, yourself. What is your perception of the beauty and strangeness of your writing? Let your writing serve as a touchstone to the embracing and loving the body you live in.

For you who don’t believe you are beautiful, write about the blank and full areas between your body and the world, the barriers you create and perceive. What are you hiding or disguising? In other words, what do you allow yourself to connect to and what do you block yourself from. What do you hide and what do you share? How authentic are you allowing yourself to be in life and in your writing? Are you really letting yourself touch the world around you, giving to that world and allowing yourself to receive from it at the same time?

There is no exquisite beauty…without some strangeness in the proportion.

–Edgar Allen Poe

Write about how you can preserve strangeness and beauty in your writing; yet claim it as yours and own it. Write about the stretch marks or scars that tell the story of who you have been. What do your freckles say about you? What are the parts about you that you know are beautiful?

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting…

….Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –…

–Mary Oliver

Comparing yourself to someone else, you can lose sight of the beauty that you bring to the world, inside and out. What bodies do you find most beautiful? Which writers, in your opinion, have the most beautiful writing style?

The most beautiful people we have known are those who have known defeat, known suffering, known struggle, known loss, and have found their way out of the depths. These persons have an appreciation, a sensitivity, and an understanding of life that fills theme with compassion, gentleness, and a deep loving concern. Beautiful people do not just happen. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

According to T. C. Boyle, “each one [story] is an exploratory journey in search of a reason and a shape.” The same is true for your writing. What makes your writing unique? Do you have a particular style? Have you modified your writing for the sake of submissions guidelines?

Explore your body as a source of empowerment and individuality. Do you express yourself through body art? Write about your body and the thoughts that shape it, the scent of your own skin, the feel of your curves. What image comes to mind that most closely resembles your style of writing, your unique voice.Are you more experimental? Do you consider your writing persuasive?

According to Sockel, “Writers lie on paper, in beautiful ways, naked and ugly, and want the world to love them for that, too. Writers sit down while the rest of us are running. Writers reign over their little piles of papers, making sandcastles out of air and calling it work.”

Becoming more comfortable with things that are labeled “imperfect” about our physical bodies can help us become comfortable with the “imperfect” aspects of our writing processes. Beauty is not fixed; we move in and out of it physically, as does our writing. How do people “become” beautiful? How do writers develop their writing voice? Writing doesn’t have to be cute or polite. Describe a time you, the author, felt beautiful despite not getting affirmation from your readers?

Writer Jeff Goins says, “When you write from your heart, your pain will become someone else’s healing balm.”[vii] During his career, author Brennan Manning learned that there is a world full of desperate, broken people, longing to hear the honest words of another ragamuffin.

A beggar unashamed of his hunger.

A thief unaware of his poverty.

A friend and addict.

A lover, liar, fighter and healer.

A paradox. Like us all.

Sources

[i] [i] Etcoff, N. Survival of the Prettiest. Retrieved January 19, 2014 fromhttp://www.nytimes.com/books/first/e/etcoff-prettiest.html

[ii] Mountain Dreamer, O. (1999). “The Invitation.” The Invitation, p. 2.

[iii] Etcoff, N. Survival of the Prettiest. Retrieved January 19, 2014 fromhttp://www.nytimes.com/books/first/e/etcoff-prettiest.html

[iv] Yeh, J. T. & Lin, C. L. (2013). Beauty and healing: Examining Sociocultural expectations of the embodied goddess. Journal of Religious Health. 52(1): 318-334.

[v] Sockel, H. (2013, April 10). Here’s Why Writers Are Ugly. Retrieved February 7, 2014 fromhttp://thoughtcatalog.com/harris-sockel/2013/04/heres-why-writers-are-ugly/

[vi] Newman, C. (n.d.). Retrieved January 19, 2014 fromhttp://science.nationalgeographic.com/science/health-and-human-body/human-body/enigma-beauty/#page=2

[vii] Goins, J. (n.d). “Why You Should Tell the Ugly Parts of Your Story.” Retrieved February 5, 2014 from http://goinswriter.com/write-ugly/

Debbie spent 30 years as a registered nurse. She became a certified applied poetry facilitator and journal-writing instructor in 2007. She is currently a student in the Johns Hopkins Science-Medical Writing program. Her publications have appeared in Journal of Poetry Therapy, Studies in Writing: Research on Writing Approaches in Mental Health, Women on Poetry: Tips on Writing, Teaching and Publishing by Successful Women, Statement CLAS Journal, The Journal of the Colorado Language Arts Society, and Red Earth Review.

Do you notice what other people wear? Do you ever feel self-conscious about your own clothes? Although we may dismiss clothing as surface-level compared to the body and personality, clothes are central to ways our bodies are experienced, presented, and understood within culture. Clothes mediate between the naked body and the social world, the self and society. Every day, we experience the bodies of others—and conceive of our own—through the medium of dress.1

Do you notice what other people wear? Do you ever feel self-conscious about your own clothes? Although we may dismiss clothing as surface-level compared to the body and personality, clothes are central to ways our bodies are experienced, presented, and understood within culture. Clothes mediate between the naked body and the social world, the self and society. Every day, we experience the bodies of others—and conceive of our own—through the medium of dress.1

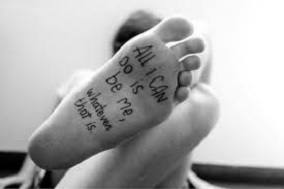

All writers are the same. We all have lungs and wrists and feet. Sylvia Plath had a belly button. Jane Austen had knees. Having this awareness embodiment makes the writers we admire more human. “Sharon Olds mentioned that after hearing a talk about Emily Dickinson, she suddenly flashed upon a vision of Dickinson’s naked foot. It was the first time it occurred to her that Dickinson had soles, toes, and ankles.”[i] It’s difficult to imagine the mundane facts of our literary heroes, to remember that they, too, are just human—with hands and elbows and fingernails, as well. Feet, specifically, are a profoundly human characteristic—they’re humble, they’re close to the ground. Think of some of your favorite writers. Imagine their toenails, their feet. How does it feel in your body to imagine these beloved writers in such a human light?

All writers are the same. We all have lungs and wrists and feet. Sylvia Plath had a belly button. Jane Austen had knees. Having this awareness embodiment makes the writers we admire more human. “Sharon Olds mentioned that after hearing a talk about Emily Dickinson, she suddenly flashed upon a vision of Dickinson’s naked foot. It was the first time it occurred to her that Dickinson had soles, toes, and ankles.”[i] It’s difficult to imagine the mundane facts of our literary heroes, to remember that they, too, are just human—with hands and elbows and fingernails, as well. Feet, specifically, are a profoundly human characteristic—they’re humble, they’re close to the ground. Think of some of your favorite writers. Imagine their toenails, their feet. How does it feel in your body to imagine these beloved writers in such a human light?