A light tap on the hotel room’s wooden door invites me to investigate. I am away on business in Newport News, Virginia, Room 203. I cross the musty brown carpet that sports faded yellow swirl patterns. Through the fisheye lens, I see a thin Indian man glancing left and right.

As a mechanical engineer for a large public utility in Colorado, I’ve been sent to the Port of Virginia to inspect a new turbine recently purchased for one of our power plants. My mind is preoccupied with the knowledge that my father arrived at this same port in January 1948, when he was merely 17 years old. He had boarded a freighter at Constanţa on the Black Sea, sailed through the Bosporus Strait to Istanbul, where he watched men load a crate of opium into a secret compartment cut into the exterior of the hull, and he saw welders seal it closed. With Asia on his left and Europe on his right, he sailed on through the Dardanelles Strait, past the ancient city of Troy, then across the Mediterranean and through the Strait of Gibraltar. The ship made another stop in Morocco where, during a brief excursion in Casablanca, dad and the half dozen other passengers narrowly escaped a mugging on the streets. Storms tossed the large freighter around like a matchbox as it crossed the Atlantic to the United States where it safely arrived at the Port of Virginia. My father successfully fled his troubled homeland of Romania just a few days before the Soviets closed the country’s borders. His parents and sisters had planned to follow a couple weeks later, but instead, they became trapped behind the iron curtain.

Dad spoke five or six different languages, none of which were English. His pockets were empty, but a kind man at the train station gave him a few dollars, enough to cover a couple meals. Here at the mouth of the James River where he disembarked, I feel the weight of his momentous journey settle into my gut.

***

With the hotel door now open, I see an Indian gentleman and recognize him as the hotel employee I saw this morning. He looks to be in his mid-fifties, yet his dark eyes are weathered by hardship or sorrow, so it seems. I wonder what type of journey had brought him to the United States. He stands straight with hands clasped behind his hips. His eyes are focused and fixed as if to study one particular button on the front of my shirt. As he clears his throat, I smell a hint of curry, which snaps my mind back to 1990 when my wife and I spent a month traveling from Bombay to Delhi.

“Excuse me sir. I clean the room. I noticed … on the table … the One Dollar. Is it for me?”

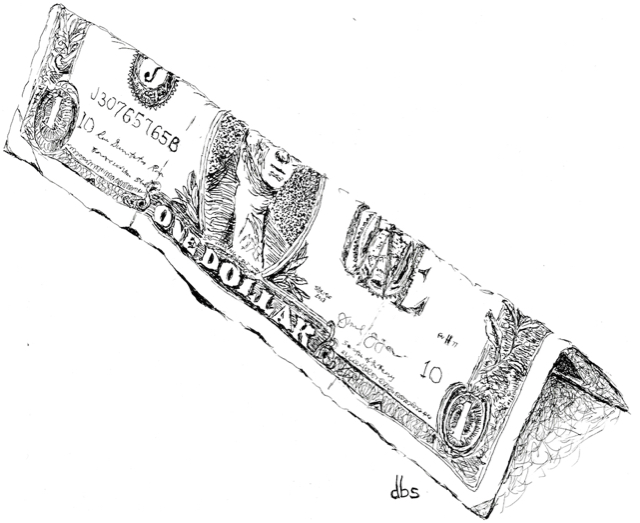

I nod and smile, raising my index finger to request a moment. I turn around and after five steps, maybe six, I pluck the bill that is still on the table, folded lengthwise, stretched out like a silent green mountain ridge on a piece of white paper that reads, “Thank You.”

I hold it out, folded still. “Yes, it is for you.” A graceful pair of fingers receives the meager tip as a secret smile floats just below the surface. He thanks me with a brief bow from somewhere above his narrow waist, then turns and hurries down the hall.

Art at the top of the page by David B. Such.