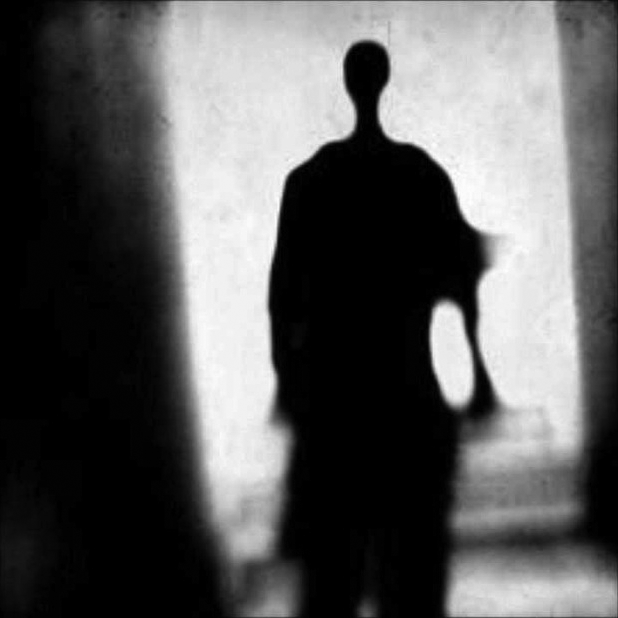

The guy at the door doesn’t look like Danny, though a case could be made for the nose. A mashed in version, dramatically scabbed and weather beaten, and the hair, filthy but spiked in defiance. A strange, Dan-like head on a body that would make an anorexic flinch. Withered limbs swimming in cutoffs and stained polo shirt. Dead-end Danny after the rock fight. It couldn’t be, yet the voice assures us it is—the South Philly accent, unmistakable.

“What have you done to the real Danny?” my wife demands.

“C’mon Andree, let me in.”

It was little more than a year ago, during the last dismal round in his squabble with the hospital administration that we saw him last. Bloodied but unbowed, he vowed to fight them to the end. Master of the cat and mouse game of drug counseling, Danny was as close to a legend as anyone in that line is likely to get. Confrontational, abrasive, street-wise to a fault, he did what you have to do to reach the reachable. The bureaucrats were another story. The end was never really in doubt.

Now he’s sitting in my kitchen eating Fruit Loops and making phone calls. The calls are brief. No one wants to hear from Danny these days. We’d heard rumors but nothing could have prepared us for the wreckage. I console myself with a single thought. Originally, he was Andree’s friend.

“I won’t give you money,” she sets the limit.

“Two bucks? Two bucks and I’m outa here.”

“I’m a nurse. I can’t give you money to cop.”

Strange, after all these years to hear her talk the talk again. He turns to me.

“Tom?”

“Jesus, what can you get for two bucks?”

He smiles. By God, it IS Danny.

“Where’s Libby and the kids?” Andree asks. Again he smiles.

***

Somewhere in the depths of her secretary desk is an in-house magazine with a faintly sneering Danny on the cover. Pre-crash and burn addict-savant in a black leather jacket. In the archives of the very hospital that fired him is a Dan directed recovery video that leaves the unaddicted feeling strangely unversed. What have we to overcome?

“Where’s little Danny?” Andree grills him. He mumbles something unintelligible.

It is her job to disapprove. Dazzled as I am by the plunge, the physical devastation, the ridiculous polo shirt, I try not to stare. It occurs to me that the bulk of the homeless once had a home and a bathroom and a closet full of clothes. This will not always be the case. The next generation is fast upon us.

He pours a small mountain of sugar on his Fruit Loops and we watch as it dissolves. The tattoos have not fared well, the dagger on his bicep reduced to a hatpin, the naked lady shriveled to a smudge. But it is the shirt that gets me. In real life Danny would not own such a thing.

Andree plays the nurse/interrogator to Danny’s strung out supplicant. They speak in code, a mix of medicalese and doper slang. All the while Danny smokes my cigarettes and shovels in the cereal. It’s a toe to toe performance, masters of the genre, Andree projecting tough love with a no bullshit bottom line, Danny, in a perfect blend of psychic pain and sardonic wit. I sit fiddling with my fingers, in the loop but out of my league.

“You want something else to eat?” I ask him. “A sandwich maybe?”

“No way, Jose. This guy gave me a sausage sandwich yesterday,” he clutches at what’s left of his stomach. “Tried to kill me, I tell ya. I said later for you, Mr. Sausage.”

Danny has a jargon all his own, Port Richmond patois laced in goofy names and words you have to look up

“I got some green chile salsa,” I make a joke. They roll their eyes and tune me out. Different treatment centers are suggested and rejected. Andree persists, Danny resists. References to HIV are impossibly oblique, pauses mostly, a hardening of the eye. It’s a pointless exchange when you stop and think. Danny invented the game. If anyone knows where the treatment centers are it’s him.

I slip him three bucks under the table.

“You need a ride somewhere?”

He reaches past me and steals another cigarette.

“Florida,” he gives a wink. “Winter’s coming, don’t you know.”

For the next hour Andree works the phone, calling in a decades worth of markers. The old girl network of admission nurses finds a place for him in the Benton Institute, though he has no medical card or even valid ID. During the negotiations Danny tells me about the car he shares with a friend on the west side.

“Well at least you can get around.” I put my clueless spin on things. His look says later for you Mr. Andree.

He was clean for seven years. Worked a job, got married, bought a house and had kids. Amazing what you can do in seven years. At the reception for his son’s christening he commandeered the stage to serenade his bride. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house. Neighborhoods. Where you can still be a hero, or even worse.

***

A week later we go to see him. Benton Institute, with it’s pillared porches and fairway grounds looks more Main Line then medicinal It’s present function, as unlikely as it’s location. Walled off from surrounding badlands, a fair share of the city’s pipers could walk there in minutes. We meet him at the med station, still wasted but showered and shaved. The only patient we’ll see who looks like a patient.

“They’re cutting me down to 40 milligrams a day,” he complains as he leads us down lavish hallways to his room. “I mean what ever happened to coddling?”

“You’re here to get well, not to get high,” Andree tows the line. As usual, my presence is not required. I trail behind them scanning the paintings and Queen Anne furniture.

“Nice place,” I tell him.

“Oh yeah, it’s like drying out in Graceland. I heard some of the rooms even have fireplaces.”

His is a corner suite with a view of the rose garden. Two single beds and a chest of drawers. Fireplace. Despite our protests he insists on showing us his feet, which have suffered some withdrawal related malady too gruesome to get into. My own toes curl in sympathy. Andree turns away.

“Will they get better?” I ask him.

Danny shrugs and wiggles the big ones at me.

“Will we?” the right one wonders in falsetto.

“Beats me,” the left one bows from the waist.

***

He didn’t last long at the Institute. A late night phone call confirmed, Danny checked out against medical advice. The news came as no surprise and whatever comes next will not include us. And I’m thinking, clawing your way back should be enough. Do the right thing and the right things should happen. But the way of addiction rigs it different. When the game is never over, how can you win?

You don’t hear much about crackheads these days, but that’s just because we got tired of listening, too much to worry about, troubles of our own. In the meantime they’re out there hitting rock bottom, the scufflers, the sidewalk sleepers, the stickman who used to be Danny.

Tom Larsen has been a fiction writer for fifteen years with work appearing in Newsday, New Millennium Writing, Puerto del Sol and Antietam Review.