My daughter Jacqueline started “honors physics” this fall despite her thinking she wasn’t good enough at math to qualify for the class. I considered hiring a math tutor over the summer. I wish my dad could just come by for homework help.

If Dad were around, Jacqueline would be “Debbie” or maybe something more exotic like “Dauphine”—a “D” name in honor of my brother Danny, not “Jacqueline” to honor the memory of my father, “Jack.”

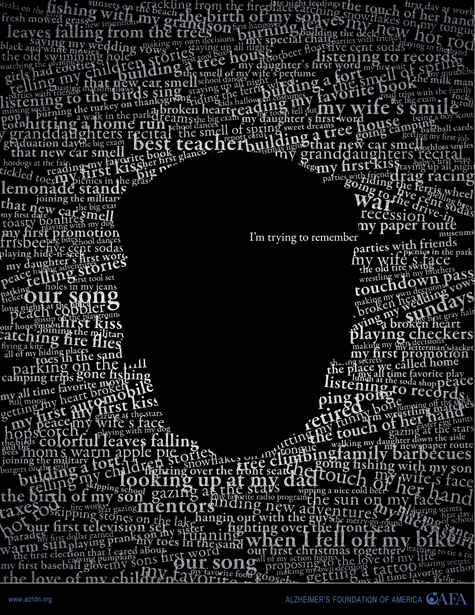

Things my father missed:

The hooding ceremony when I got my doctorate

Me landing a tenure-track job

Jacqueline’s birth

Me quitting the tenure-track job

Jacqueline’s bat mitzvah

At the end of the summer I’ll celebrate my 50th birthday, and my dad will miss it.

Like he missed my 40th.

Also my 30th.

Grandpa was almost 100 when he died.

Daddy missed that too.

Grandpa and his four siblings lived well into their nineties.

I was robbed of four decades with Dad.

Speaking of birthdays, my 10th was in 1978. That’s the year one of the most iconic moments in movie history was imprinted in my memory:

A bereaved Superman played by Christopher Reeves cradles the lifeless body of Lois Lane, killed during a massive earthquake. In his agony, Superman lets out a primal scream and takes off flying. Whoosh! The camera pans out and cuts to a view of Earth from outer space where bluish-white lines streak around the globe at the equator in the opposite direction of the planet’s rotation—zip, zip, zip—about 17 times!

At which point the Earth actually stops! Then reverses!

Next, those bluish-white lines whiz around the planet a few times the other way, Earth goes back to rotating in its regular direction, and Superman flies back down to the surface of the planet, arriving in time to save Lois Lane—before she dies!

What would you do if you could turn back time?

⧳

“Daddy, how come you became a mathematician?”

“Because there’s safety in numbers.”

When Superman came out, my father coauthored what I later learned were seminal papers characterizing the “seismic inverse problem.” Those papers are written in a foreign language called mathematics, filled with Greek symbols and notations indecipherable to me.

“What’s it mean, Daddy?”

“They take a spikey-mikey, and they put it in the ground and make it go ‘boom,’ and these equations graph the vibrations that bounce back.”

| |

Pop quiz: |

|

| |

Lois Lane’s 1972 Ford Galaxie is traveling in a straight line at top speed on a dirt road when it runs out of gas. Calculate how far it will travel on fumes and momentum before a massive earthquake splits open the road and buries the driver alive inside the car. |

|

| |

Hint: Assume the car is red. |

|

I got my driver’s license in 1984.

“Keep this in the trunk in case of emergencies,” Dad instructed, handing me a can of S&W kidney beans as visions of me stranded on I-25 during a blizzard flashed before my eyes. Until Dad deadpanned, “In case you run out of gas.”

Cut to 12 years later. Our hero opens the door of the house leading into the garage. The camera tracks him as he walks over to his silver Honda Accord and climbs behind the wheel. Cut to a shot of a hand turning the ignition key. Cut to outside where a yellow Honda Prelude pulls into the driveway, waits for the automatic garage door to open, then pulls alongside the Accord. Moments later, we hear a woman scream.

The retired police officer who lived next door to my parents performed mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, but it was too late.

⧳

My parents had lived in the house next to the retired cop about 18 months. They’d had it custom built about 30 minutes outside of Denver, near the university where my father worked. The idea was to get a fresh start after my brother died at the age of 28 from familial dysautonomia, a rare and degenerative neurological disease he’d had from birth.

Mom and Dad liked that the new house had wraparound decks and windows with views of the Rockies. They liked that the curved driveway meant the garage didn’t face the street. Garage doors are ugly.

My parents threw a party for me and my then-fiancé at that house in March, then came to LA for my wedding in May. Dad’s physical was in July.

A weightlifter, jogger, and hiker, Dad’s health was excellent except for a terrible malaise he couldn’t shake. His sense of purpose had died along with my brother. His concentration and enthusiasm had waned. He confessed to feeling washed up as a theoretician. Another academic year was about to start, and the prospect of facing graduate students the same age as Danny when he died felt like more than Dad could bear. The physician had also been my brother’s doctor. He knew our family well.

The doctor suggested my father speak with a mental health provider. He gave Dad a list of therapists to call, but only one had an immediate opening. That’s the one Dad went to see. Appointments were set for one hour, every other week. The psychiatrist prescribed Prozac. Within three months, Dad was dead.

The so-called “Happy Pill” didn’t take away my father’s grief. It didn’t improve his concentration nor renew his sense of purpose. What’s more, my mother confided later, after beginning his course of drug therapy, her formerly virile husband was unable to maintain an erection. Not realizing this was a common side effect of antidepressants, this distressing new symptom contributed to Dad’s spreading sense of hopelessness.

Days before his suicide, my father’s demeanor took a drastic turn. He was flirtatious with a colleague’s daughter, Abby—my friend whom Dad knew from the time she was born. Alarmed at his uncharacteristic behavior, Mom left frantic messages for Dad’s psychiatrist, “He’s too high! He’s going to crash!”

As usual, the psychiatrist didn’t return Mom’s calls.

The morning of Dad’s death, Mom accepted a call to substitute teach. That day, she says, my father seemed better than he had in weeks. “He had on a pink shirt, and he’d just shaved. He was smiling one of his gentle smiles. I said, ‘You look so well!’ ‘You look adorable!’ he said.”

| |

Warning: |

|

| |

In 2007, the FDA-mandated “black box” labels, its strongest consumer alert, for a class of antidepressants including Prozac, specifying that the medications can cause suicidality in children, adolescents, and adults younger than 25. Irregularities in clinical trials led some FDA reviewers to recommend adults over 25 be included in the warning. The FDA-mandated labels urge close monitoring of all patients regardless of age, “especially during the initial few months of a course of drug therapy, or at times of dose changes, either increases or decreases.” |

|

⧳

I took a night flight to Denver from LAX, sitting in the last row of the plane. The man beside me peppered me with questions about the book in my lap. In 1996, earbuds and headphones were as common as black widow’s veils.

Hurtling through space at 500 miles per hour, politely answering the man’s questions, my father was like Schrödinger’s cat—dead and not dead, simultaneously. When the plane came to a halt at the gate, the man retrieved my luggage from the overhead bin. Was my Colorado visit for business or pleasure, the man wanted to know. Dead? Not dead? In the time it took me to contemplate the possibilities, a funny look must have passed across my face. Suddenly my chatty seat mate looked like he’d had a swig of sour milk. “Sorry, so sorry,” said the man. A black veil would have spared us both embarrassment.

Riding the airport’s people mover, the possibility remained that my father would greet me at our usual spot near the top of the escalator. My heart in my throat, I rode that escalator. When I reached the top, it was Abby waiting there.

The garage door at my parents’ house was open when we arrived, and big fans had been set up inside. Where was my father? Did those big fans blow him away?

⧳

By coincidence, the Annual Meeting of the Society of Exploration Geophysics, of which my father was a member, was in Denver that year, just three weeks after my father’s death suicide.

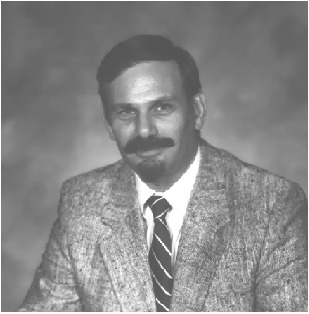

At the urging of one of Dad’s colleagues, I showed up for the memorial scheduled during the convention, figuring it would be like the panels at my academic meetings: Maybe 20 people in a dingy hotel conference room, Dad’s research as a springboard to a discussion of current research. My father had always been humble about his work. “It’s not that I’m so brilliant,” he’d told me. “I’m just a hard worker.”

Given my low expectations, I wasn’t prepared for what I encountered. The meeting turned out to be at Denver’s gleaming new convention center, the session honoring Dad in an enormous ballroom filled to standing room only. Mathematicians, computer scientists, academics, industry people employed by energy or tech companies—stricken-looking people, most of whom I’d never seen before—traipsing up to the lectern, one by one.

“That face,” moaned one, hand out, palm up, fingers curled—cupping an invisible chin.

Another recalled my father’s droll wit. When asked for a simple explanation of “inversion” techniques compared with the “migration” methods, my father had rattled off proponents of inversion, a list replete with Semitic surnames. “Don’t you see? Inversion is Jewish migration!”

One of Dad’s former graduate students told of submitting his thesis proposal. My father had pointed out the error in the idea. Several days later, Dad called the fellow to his office. The student braced himself for the message that he simply wasn’t doctorate material. Instead, Dad had filled several whiteboards with mathematical proofs and proceeded to demonstrate why the student had been correct. And why Dad had been wrong.

The portrait that emerged from the accounts of these strangers corresponded perfectly with the portrait of my father I carried around in my head. “That face”—beloved and admired enough to fill a ballroom, that face was the same in public as the one I recognized from home.

I sat there in that ballroom wishing I’d brought my mini tape recorder or even just a pencil. I tortured myself with the thought that I’d arrived so ill equipped while simultaneously trying hard to track exactly what was being said, so I could commit the entire affair to memory, verbatim.

Except I couldn’t because of all the references to names and companies and specialized terminology. Because my brain wasn’t working right. Because I was in shock. Because the person they were talking about wouldn’t have killed himself.

⧳

When I was 8 years old and won a bike at a school raffle, Dad sprang for his own first set of wheels. The two of us learned to ride our bikes together in the vacant parking lot around the corner from our house.

Despite his late start, Dad became an avid cyclist. He could take his bike apart, down to the ball bearings, then put the whole thing back together, good as new. He was intimately familiar with every bike lane in the metro Denver area, every strip of uneven pavement, every back alley shortcut.

He’d strap bungee cords around a cardboard box containing hole-punched cards onto the back of his bicycle, don his helmet, clip one of those nerdy side mirrors onto his Foster Grants, and off he’d go—to feed those cards into the IBM mainframe computer at the Denver Tech Center.

Now I carry around a much more powerful computer I can slip inside my back pocket.

“Hey Siri. Show me psychology articles on suicide by car exhaust.”

“Here’s what I found on the web for ‘show me psychology articles on suicide by car exhaust’:”

The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry published a study of hospital patients receiving treatment for carbon monoxide poisoning after surviving deliberate exposure:

| |

1. |

Subjects reported choosing this suicide method because of the accessibility of motor vehicles, because of the method’s painlessness and because they were aware of the method’s lethality. |

|

| |

2. |

Most subjects denied excessive time spent planning. Few had composed suicide notes. Regret of the attempt and lack of further suicidal ideation afterward were common traits among these patients. |

|

| |

3. |

Low suicide intent scores indicated the attempts were impulsive acts. |

|

| |

4. |

The most common diagnosis in this group was adjustment disorder with depressed mood. |

|

⧳

“It sounds like your father had a hard time experiencing joy,” said my psychologist. The therapist had a Ph.D. Many books lined his shelves. My husband and I had been seeing him for couples therapy, but grief counseling seemed more pressing in the wake of Dad’s suicide.

Hmmm. Father. Hard time experiencing joy. I mulled over the therapist’s words, my brain flashing through images of Dad: animated over a new jazz recording. Engrossed in a book of Greek philosophy. Planting a passionate kiss on Mom’s mouth. Biting into a plump nectarine and letting the juice run into his goatee. Dad’s outgoing message on our telephone answering machine: “We can’t answer the phone right now. Please leave your name, number and maximum bench press. Beep!”

Suicide is all this therapist knows about my father. There’s so much more I urgently need this therapist—and my husband—to know.

Sitting on the therapist’s beige couch I see myself sitting on a boulder beside a mountain stream. I pull off my dusty clutter boots and shake them out, then Daddy takes them along with his Army surplus knapsack and goes jogging back to where the Toyota’s parked. He returns with our sandals and a canteen of fresh water and, “One! Two! Three!!!” we plunge our feet into the icy currant, and I squeal, “Aiee!” Daddy smiles his Buddha smile and sighs, “Ahhh.”

I don’t tell the therapist about the post-hike ritual. I don’t mention the nectarine or Dad’s message on the answering machine. Instead I say lamely, “But my father enjoyed lots of things.”

The therapist rotates the ankle of his crossed leg. My husband arches his eyebrows. Taking in the subtle gestures my protest elicits, I feel myself negated, reduced to some Freudian theory about daughters idolizing fathers. The therapist’s ankle, my husband’s expression, the beige-colored silence in the psychologist’s office are like my old wool hiking sock shoved in my mouth: suicide, therefore, depression. All else irrelevant, nothing more need be said.

⧳

I can’t remember who suggested I join a grief group. I called the big medical center near my house, and someone there referred me to “Survivors of Suicide,” a support group operating under the counseling program at the University of Judaism. You weren’t allowed to attend meetings until the person who’d killed himself had been dead for 6 months. I don’t know why, but rules are rules.

I got lost driving to my first meeting. Actually, no, I wasn’t lost, just not expecting it to be so far away and panicking because it was rush hour and I was upset about stop-and-go traffic and being late and about going to a group for suicide “survivors”—and that joining implied the suicide was actually real.

I pulled off the freeway to consult a map. After satisfying myself that I hadn’t missed my exit, I executed a U-turn to get back on the freeway. Across a set of double yellow lines.

I nearly bumped my head on the roof of the car when I heard a loud siren and saw lights flashing in my rearview mirror and a man’s stern voice through a megaphone ordering me to pull over.

I kept my face blank while the police officer quizzed me about my infraction (“Do you know why I’ve pulled you over?”) and checked my driver’s license and registration as a heated argument with myself ensued inside my head.

“Tell him where you’re going and bust out crying, and he won’t write the ticket!”

“That old cliché? It’s straight out of ‘I Love Lucy!’”

“Do it!”

“No way!”

Meanwhile the officer tore off the ticket and handed it to me. Only then did I say, “I’m going to a Survivors of Suicide meeting at the University of Judaism, and I’m lost.” The officer just blinked at me. Finally he said, “Follow me,” and hopped back on his motorcycle, lights flashing, and Interstate 405 parted like the Red Sea as I enjoyed a police escort all the way to my freeway exit.

It was awfully nice of the officer, but I still had to pay a $100 ticket and take a daylong driver safety course.

I couldn’t relate to much of anything that was discussed at the Survivors of Suicide meetings, but I kept going anyway, like when my mother cooked calves liver for supper and told me to eat it because it’s packed with iron. Week after week, I tried to square stories of loved ones who’d repeatedly slashed their wrists or filled journals with drawings of tombstones and demons with everything I knew—or, by then, began to wonder if I merely thought I knew—about my father.

The other people in the group spoke of loved ones who were “badly damaged.” “Wired wrong from birth,” one mother said of her son. “Tried three times,” said a young woman about her friend. Words like “obsessed,” “compelled” and “inevitable” came up a lot. Another word that came up was “empathy.” Going through something as painful as a loved one’s suicide cultivated empathy. That was the consensus of the survivor group.

| |

Bedtime prayer: |

|

| |

“Hi, Almighty, it’s me. Howsabout a trade? Jimmy, my mother-in-law’s blowhard husband, for my father?” |

|

| |

Postscript: My heart went out to my mother-in-law when her husband died a few years later. What those people in my support group said about empathy must have been right. |

|

After one of those meetings, I remember screaming at my husband, “My father was nothing like that!”—referring to those the suicide survivors group had lost.

| |

Fact check: |

|

| |

My husband claims what I actually said was, “Those people were losers!” To the extent that I may have chosen such an unfortunate word, my sincere apologies to anyone who’s ever lost someone to suicide. I’m not sure my husband’s remembering that right—but if I did say “losers,” I’m fairly sure my husband and I were arguing, so I was probably frustrated and saying extreme things I didn’t mean. |

|

Why was I screaming? Because of the obscene cosmic absurdity that a man like my father had taken his life. And because I was choking on the wool sock shoved in my mouth by the therapist who rolled his ankle, the spouse who arched his eyebrows, the traffic cop with the fallen face, the group of survivors to whom I couldn’t relate.

I felt like a gutted fish, mouth opening, mouth closing, no sound coming out or none that would be believed. Because . . . suicide. Particulars didn’t matter. Pointing out particulars only proved the point: You know what they say about daughters and Daddy fetishes.

For more than 20 years, a big part of me has remained that gutted fish, unblinking eyes incapable of tears. Until just the other day when I finally cried a few of them.

I was driving along, thinking about my 50th birthday coming up and sort of daydreaming about a party when it hit me: “Daddy was 56!” That’s when the tears came, for the first time in maybe ever.

And those tears felt good. I pulled my car over and smiled a little to myself and took a minute to appreciate my father and imagine myself in his shoes.

He was all of 26 when my brother was born. At 26, I regularly ate two bowls of Honey-nut Cheerios and called that dinner. At 26, my father had a doctorate to finish, a family to support, a son with a disease most doctors had never even heard of, let alone treat. Dad sang us nursery rhymes and folk songs and read us books and paid the bills and did his best to make our family feel happy and safe, and we did.

Along the way, he had no signposts like “odds are your son will be unable to walk by this age,” or “renal failure by that age,” so Dad just did his best when Danny was well, believing he’d survive. And he did his best when Danny was sick. I never heard him beating his chest about any of it. He remained emotionally present, didn’t turn to alcohol or drugs. Day after day after day for 28 years, the whole time engaged in intellectually demanding creative work. I don’t know how he managed it.

If that moment in my car had been a scene in a movie, this is when the camera would pan out, and you’d see my car pull away from the curb and cruise slowly down a tree-lined street under Kodachrome skies. Gently uplifting music would play, something like Hans Zimmer’s score, “This Land,” from the Lion King soundtrack.

[Insert record scratch sound effect here]

“Hey Siri . . .”

“Go ahead, I’m listening.”

“Was my father’s suicide an act of passion, or was it premeditated?”

“It sounds like talking with someone might help. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline has confidential, one-on-one, 24 hours a day. Would you like me to call them for you?”

“NO!”

“OK.”

“Show me articles about suicide being an act of passion or premeditated.”

“Here’s what I found on the web for ‘suicide being an actor passion or premeditation’:”

| |

1. |

A Harvard study of survivors of nearly-lethal suicide attempts concluded the acute period of heightened risk of suicidal behavior is often mere hours or minutes. |

|

| |

2. |

Harvard’s Injury Control Research Center statistics indicate suicide methods requiring forethought or exertion—implying premeditation, e.g. wrist slitting—have the lowest chance of “success.” Methods requiring the least effort or planning happen to be the deadliest. Consequently, those most closely fitting the classic definition of “suicidal” might be “safer” than those who act impulsively. |

|

| |

3. |

A landmark study from the Berkeley School of Public Health of the 515 would-be jumpers who’d been pulled off the Golden Gate Bridge between 1935 and 1971 culled death-certificate records to determine only six percent went on to commit suicide. “The vast majority had passed through an acute, temporary crisis, came out the other side and got on with their lives.” |

|

The Berkeley study was published 40 years ago in 1978, when Superman grieved onscreen for Lois Lane.

Just what was going on in that scene when Superman caused time to reverse? The Earth weighs six septillion kilograms (6 * 1024 kg) and is spinning at approximately 460 meters per second, around 1,000 miles per hour. So wouldn’t the force required to cause Earth’s rotation to stop, reverse, and then reverse again actually destroy the planet?

I don’t need honors physics to know it doesn’t matter. If turning back time would stop Lois Lane from dying, Superman would do it.

##