A person will sometimes devote all his life to the development of one part of his body –the wishbone. –Robert Frost

Our bodies respond to our thoughts, emotions, and our inner spirit. In this column you will be asked to dialogue with your body and explore what your body has to say to you.

The body never lies. The body says what words cannot. –Martha Graham

If we listen to our body’s language, we may learn that a stiff shoulder carries the weight of our stress, or that a locked jaw holds unspoken words. Listening and appreciating our body’s knowledge is essential to a healthy relationship with our body, and just by extension our writing and our voice.

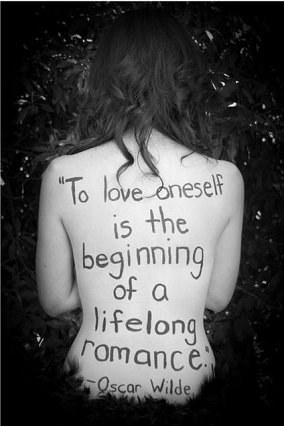

Dialoguing with our body (body parts, your body’s capabilities, your inner healer) will facilitate your awareness and connection within yourself to your body. For example, if you don’t like how your thighs look, think about their strength, their power, the way they can wrap themselves around a lover. If you’re not happy with the shape of your nose, think about all the amazing aromas it allows you to enjoy. Let these grateful acknowledgements become seeds for you to express love for your whole body, in all its imperfect glory.[i] In writing about your body, write about any messages recieved, behaviors or patterns observed. Feel free to draw a symbolic image of any message(s).

A poem to inspire you to dialogue with your body:

“Praise What Comes”

Jeanne Lohmann

Praise what comes

Surprising as unplanned kisses, all you haven’t deserved

of days of solitude, your body’s immoderate good health

that lets you work in many kinds of weather. Praise

talk with just about anyone. And quiet intervals, books

that are your food and your hunger; nightfall and walks

before sleep…

…the jumping-off places between fear and

possibility, at the ragged edges of pain,

did I catch the smallest glimpse of the holy? (lines 1-6, 13-15)

Adrienne Rich’s beginnings as a poet can be traced back to a forgotten moment in childhood when, as she says, describing what is in effect a Lacanian entrance into the Symbolic, “my mother’s feminine sensuousness, the reality of her body began to give way for me to the charisma of my father’s assertive mind and temperament…and he began teaching me to read”[ii] What does it feel like in your body to jump between fear and possibility?

In her book, Women’s Bodies, Women’s Wisdom, Dr. Christiane Northrup instructs her patients to ask what their bodies are trying to tell them and write about it in their journals. One woman asked her pelvis what wisdom it was trying to express through her fibroid and heavy menstrual bleeding. She waited for several days until her body responded, “Your periods are symbolic of the way you give yourself away too freely. The heavy bleeding represents your own life’s blood draining away.”

Have a conversation with your body—features you particularly love, gratitude for your body’s capabilities. Think about a friend –the good, the awful, the hilarious. Dialogue with your body as if it were your best friend. Think about the part of your body you’ve treated poorly, judged, or were reluctant to embrace. Write a letter to that part of your body. Add some humor.

What does your writing say about how you relate to your body? Your attitudes and feelings towards your body? What does your body most need?

The following exercises may help you get started with having a conversation about/with your body.

Exercise 1: Dialogue with, a body organ or part; your voice, your goddess, inner healer, or sage. Alternate your name with the name of who or what you want to dialogue with. Give yourself plenty of time.

Exercise 2: For further exploration of dialoguing with the body, feel free to also consider dialoguing with an emotion, whether it is present or absent: anger, hate, or rage, love, sadness, pain, guilt, fear or with survival, attitude, vulnerability, belonging, security, being grounded, boundaries, taking risks, a shadow world, your authentic self. What do each of these things feel like in your body?

You can also write about specifics: such as muscular legs, holding hands, a tanned back, perfume and heels, boots and belts, straps and hooks, body art, body fluids or the naked truth.

Summary exercise: When you feel the dialogue is complete, ask, “Is there anything more?” Trust the process. Acknowledge what you are grateful for.

[i] Brandeis, (2002). pp. 188-189.

[ii] Quoted in Helen Vendler, (1980). Part of Nature, Part of Us: Modern American Poets, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England, p. 263.

Debbie spent 30 years as a registered nurse. She became a certified applied poetry facilitator and journal-writing instructor in 2007. She is currently a student in the Johns Hopkins Science-Medical Writing program. Her publications have appeared in Journal of Poetry Therapy, Studies in Writing: Research on Writing Approaches in Mental Health, Women on Poetry: Tips on Writing, Teaching and Publishing by Successful Women, Statement CLAS Journal, The Journal of the Colorado Language Arts Society, and Red Earth Review.

One puts down the first line…in trust that life and language are abundant enough to complete it.

One puts down the first line…in trust that life and language are abundant enough to complete it.