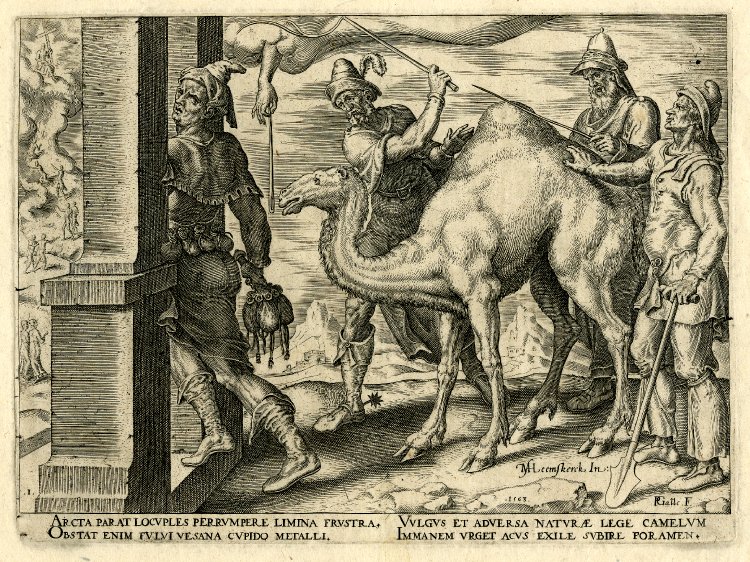

How do those who claim to be Christians today reconcile the modern world’s quest for material gain with Jesus’s severe injunctions against riches? Most notably in verses 10:25-26 of The Gospel According to Mark: “But Jesus answereth again, and saith unto them, Children, how hard is it for them that trust in riches to enter into the kingdom of God! It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God” (King James version).

I suspect a representative answer came from a pink-cheeked young business major when I asked that question in a core literature class years ago. Without a second’s hesitation, he told me, “Things were different then.”

And so they were. According to theologian Sakari Häkkinen, “In the Ancient world poverty was a visible and common phenomenon. According to estimations 9 out of 10 persons lived close to the subsistence level or below it. There was no middle class. The state did not show much concern for the poor.” In fact, exploiting the poor was the primary source of income for the fraction at the financial top who made their fortunes as provincial governors, tax collectors and moneylenders. By condemning the rich abusers, Jesus was, in effect, preaching to the destitute choir.

Leap ahead fifteen centuries when flourishing proto-capitalistic commerce in Europe spread the proceeds of trade, and the good life was enjoyed by an expanding middle class. As seen in the meticulous details in paintings by Jan van Eyck, Pieter de Hooch, Rogier van der Weyden, and others, material objects were prized, driving the accumulation of the profits needed to acquire them.

This new emphasis on the things of this world is explained by Harold J. Cook in Matters of Exchange: Commerce, Medicine, and Science in the Dutch Golden Age. Ships sailing about the known world made the acquisition and sharing of physical goods a possible goal. Scientists transformed their field by turning their attention to the study of concrete articles. Nonscientists—a larger number—attributed great value to concrete possessions. An expansion in disposable income led to a consumer revolution. A large proportion of this new wealth was spent on literal consumption. Merchants and others with the means were “acquiring well-crafted furniture, linens, antiquities, painting and sculpture, books and manuscripts, strange and lovely items of nature, and other rare and beautiful objects.” Cook concludes that “Valued objects had become ‘goods’ alongside personal virtues. As the historian of art and society Richard Goldthwaite has put it, ‘possessions become an objectification of self,’ perhaps ‘for the first time.’”

But what about Biblical condemnations of riches? In a period when Europeans took the Bible much more seriously than they do today, the affluent sought a loophole to avoid the threat of Mark 10:25-26. Would accumulations of fine jewels, linens, and spices of the East condemn the owners to forsaking eternal salvation?

The Renaissance theologian, poet, and historian Caspar Barlaeus (1584–1648) proposed an answer by defending commerce as beneficial to virtue and wisdom. His argument is explained by Cook. Before Barlaeus, Dirk Volkertsz Coornhert, in 1580, wrote that wealth and virtue were compatible if the profits were given to charitable causes or even supporting military defense. The critics of this position asked why anyone would seek profits they couldn’t keep.

Barlaeus took a different tact, defending self-interest as natural and essential to social interaction, mutually supporting others and ultimately fulfilling God’s purpose for each of us. He claimed that great wealth led to great learning and that virtue and magnificence came from the union of learning and worldly activity. Cook summarizes the core of Barlaeus’ beliefs: “It was not from doctrine but from the interactions found in buying and selling, and in the search for knowledge that was another aspect of exchange, that modesty, honesty, and natural truths emerged.”

While a camel might be stymied by the needle’s eye, a Dutch burgher would sail right through. That is, because for Barlaeus, as much as he defends the basis of capitalism, wealth was not an end in itself but rather a means to the betterment of society and human kind. In his more carefully formulated argument, he echoes my pink-cheeked student in justifying the differences of his period’s economic circumstances from the time of Jesus.

Today, we appear to be in a throwback to Galilean imbalance, with wealth burgeoning exponentially for the few. Inequality is escalating, the top 0.1 percent having as much of the bottom 90 percent. While the 90 percent don’t live in Galilean poverty, the middle class is withering, the working class falling behind, millions resentful at the loss of what they once had and seeing no promise of regaining it. Rather than following Jesus by threatening the rich with the loss of heaven, they—unaware—are closer to Barlaeus in calling for a reallocation of wealth to achieve a better society. Yet, we are a long way from the modesty, honesty, and truth that might result from a search for knowledge.

##

Sources:

Harold J. Cook. Matters of Exchange: Commerce, Medicine, and Science in the Dutch Golden Age. Yale University Press, 2007.

Sakari Häkkinen. “Poverty in the first-century Galilee.” HTS Theological Studies, 2016

Photo at the top of the page: © Trustees of the British Museum.