I walked in rectangles, city blocks. Not that you were in reach. I knew not only that I would not find you, but that you did not want to be found. With each lap I extended the size of my rectangle, a block farther in every direction. I would find you and you would reject me and I would try to work my way past that, as I had done every time before.

I looked for you in bars, but I did not stop for a drink. I was never much good at stopping. When I stopped it would mean I had found you or I had given up. Then I would start drinking, and I’ve never been good at stopping that either.

It was early evening when my walk began, not quite dark. I’d gotten home from work and you weren’t there. Nor were your things. I saw the bathroom cabinet emptied of everything but toothpaste and shaving cream and I knew you had left me. I checked the closet for your clothes anyway, but I knew that if your skin lotions were gone you were as well.

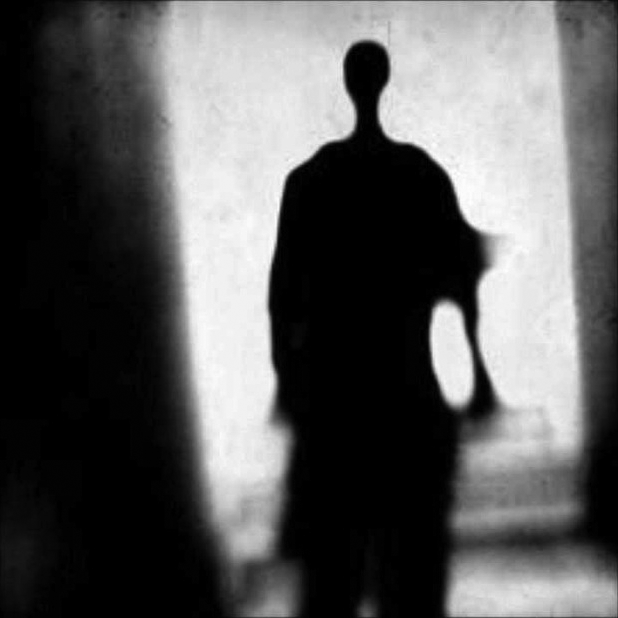

If I locked the door when I left the house I did it automatically. I barely remembered to put my shoes back on. I walked into the dusk then. Now, perimeters broadened, I walked into the dark. If I do not find you I will walk into the dawn, but the dark will never leave. The night will grow colder, and I will find myself farther and farther from home. Without you that is all I will ever find.

Rob Pierce is the Editor-in-Chief of Swill, and for nine years was one of the editors of Monday Night. His prose has been published or accepted for publication by Swill, Monday Night, Zygote in My Coffee, Five Star Literary Stories, Strange Tales of an Unreal West, and the forthcoming album release by The Ancients.