“I have grown determined to prove that the art of literature

is more resilient than what menaces it.

The best defense of literary freedoms lies in their exercise,

in continuing to make untrammeled, uncowed books.”

Joseph Anton, aka Salman Rushdie

By 1989, Norman Mailer was championing an ex-ad man who was to become the most infamous literary troublemaker of the 20th Century: Salman Rushdie.

The Satanic Verses had earned “the Godfather of Indian Literature” an Ayatollah fatwā and a million dollar bounty on his head. Joining Susan Sontag, E.L. Doctorow, Don Delillo, Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, and other colleagues who declared, “We’re all Salman Rushdie now,” Mailer participated in a public reading of the Verses. The event, said the novel’s Doubleday editor, Gerald Howard, “broke the fever of fear the literary world was living in.” After the reading, Mailer wrote to the fugitive then hiding out in London under the pen name, Joseph Anton, honoring Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov.

“Many of us begin writing with the inner temerity that if we keep searching for the most dangerous of our voices… we will outrage something fundamental in the world and our lives will be in danger,” wrote Mailer. “Now you live in what must be a living prison of contained paranoia, and the toughening of the will is imperative, no matter the cost to the poetry in yourself.” At the time, Rushdie was being burned in effigy, and bookstores carrying his fourth novel were being firebombed. Mailer went on to express his hope that his beleaguered colleague would escape “martyrdom,” be “embraced by the muses,” and go on to create a major piece of fiction, which would “rejuvenate” modern literature.

Rushdie later told the Paris Review, “I was actually strengthened by the history of literature — Ovid in exile, Dostoyevsky in front of the firing squad, Genet in jail.” Just after the announcement of the fatwā, another esteemed ally of his, Tony Harrison, released The Blasphemers’ Banquet, a film starring his historic role models Voltaire, Moliere, and Byron. Meanwhile, when B. Dalton announced its intention to remove Rushdie’s title from their shelves to avoid a firebombing, Stephen King delivered an ultimatum to the rattled chain: “You don’t sell Satanic, you don’t sell me.” So Dalton caved to the master of horror himself.

Even so, Rushdie was a not hero and standard-bearer for everyone in the literary community. Germaine Greer called him a “megalomaniac,” and Ronald Dahl “a dangerous opportunist” who was jeopardizing the lives of others. His Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, was fatally stabbed in ’91; his Italian translator, Ettore Capriolo, was also shanked; and his Norwegian publisher, William Nygaard, was gunned down in the street.

“Until the whole fatwā thing happened it never occurred to me that my life was interesting enough,” the Indian novelist confessed to the Paris Review, acknowledging that his earlier work had not merited the attention that his “Naughty but Nice” creamcake ad campaign had at the outset of his literary career. Indeed, there was a silver-lining to the Khomeini’s price on his head: it earned the magic realist a French Ordre de Arts Commandeurship, a British knighthood for “services to literature,” and six-figure advances. Not to mention U2 backstage passes and Bono shout-outs at Wembley, and serial wives (in lieu of seventy-two virgins) who played beauties to his literary beast.

Unable to shut the infidel down with time-honored techniques, the jihadists were fit to be tied. They couldn’t exile Rushdie like Dante, Defoe, or Dostoyevsky, because he was already an exile and the civilized world his oyster. They couldn’t burn him like Savonarola, Hypatia, or Servetus, or jail him like Voltaire, Gorky or Wilde, because they couldn’t find him even at Wimbledon, the ICC Cricket finals, or a Sag Harbor literary fete. And they couldn’t cut his head off like Cicero, Raleigh, or More because, even if they did track him down, he was under protection of the British crown and Bono himself!

Like his late great predecessors, Sir Rushdie defined the exemplary writer as “an arguer with the world.” Since he seemed to be winning his argument in the Western world, if not the Middle East, he had decided to stop “sulking and hiding,” as he put it, and to “rededicate myself to our high calling.”

Thus the burning and bloody history of literary recycling ended with this glorious triumph of the First Amendment penned by the first American revolutionaries.

Speaking for all other irrepressible arguers with the world, Salman Joseph Anton Rushdie put the history of outlaw literature in a nutshell for BBC News magazine: “What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.”

David Comfort’s earlier popular nonfiction titles were released by Simon & Schuster and Kensington. Excerpts from his latest title, An Insider’s Guide to Publishing (Writers Digest Books) appear in Pleaides, The Montreal Review, Stanford Arts Review, InDigest, Writing Disorder, Eyeshot, Glasschord, and Line Zero. His current short fiction appears in The Evergreen Review, Cortland Review, The Morning News, Scholars & Rogues, Inkwell, and Eclectica Magazine. He is a Pushcart Fiction Prize nominee, and a finalist for the Faulkner Award, Chicago Tribune Nelson Algren, America’s Best, Narrative, Glimmer Train, Red Hen, Helicon Nine, and Heekin Graywolf Fellowship.

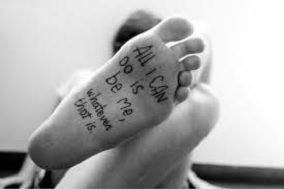

All writers are the same. We all have lungs and wrists and feet. Sylvia Plath had a belly button. Jane Austen had knees. Having this awareness embodiment makes the writers we admire more human. “Sharon Olds mentioned that after hearing a talk about Emily Dickinson, she suddenly flashed upon a vision of Dickinson’s naked foot. It was the first time it occurred to her that Dickinson had soles, toes, and ankles.”[i] It’s difficult to imagine the mundane facts of our literary heroes, to remember that they, too, are just human—with hands and elbows and fingernails, as well. Feet, specifically, are a profoundly human characteristic—they’re humble, they’re close to the ground. Think of some of your favorite writers. Imagine their toenails, their feet. How does it feel in your body to imagine these beloved writers in such a human light?

All writers are the same. We all have lungs and wrists and feet. Sylvia Plath had a belly button. Jane Austen had knees. Having this awareness embodiment makes the writers we admire more human. “Sharon Olds mentioned that after hearing a talk about Emily Dickinson, she suddenly flashed upon a vision of Dickinson’s naked foot. It was the first time it occurred to her that Dickinson had soles, toes, and ankles.”[i] It’s difficult to imagine the mundane facts of our literary heroes, to remember that they, too, are just human—with hands and elbows and fingernails, as well. Feet, specifically, are a profoundly human characteristic—they’re humble, they’re close to the ground. Think of some of your favorite writers. Imagine their toenails, their feet. How does it feel in your body to imagine these beloved writers in such a human light?