It is the silken hour of morningtide as a fat, polka-dot spider crawls along the edge of a dust and plaster-encrusted windowsill. Briefly, it pauses to examine a vertical, paint-smeared iron bar: one of three that obstruct an easterly view out of a small, broken glass window, above a narrow, rectangular bed, where a short, thin man lays sleeping, sleeping still. Then, forward-march, and the spider moves from light into shadow, from shadow into a thin, tapered crack of crumbling mortar that flakes and falls in a spatter of powdery ash upon the twisted countenance of the sleeping man.

The man yawns . . . coughs . . . rolls onto his side, extending one skinny arm – with a zodiac tattoo of a fish on the wrist – over the edge of the bed.

***

Look closely now at this arm and you will see a thin, bluish vein pulsing meno mosso to a kind of legato sparkplug music that only he can hear: just there, above the bearded, twitching thumb: one and two . . . and . . . two and one . . . and . . .

***

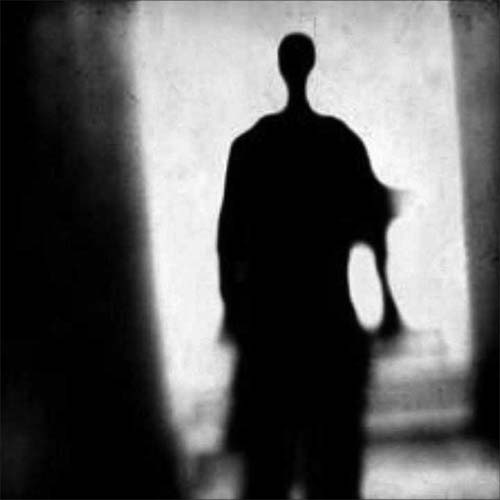

The man is now fully awake, alert, his eyes wide open and staring up blindly into the black hole of recall (Who? Where? What the hell?). His sense of the moment slip-ping away from him, like a ball rolling tirelessly on, taking a little side trip, as it were, from time in attendance; a side trip to a place that is dark, though not unpleasant – a sort of indeterminate state filled with predatory memories. And then, of a sudden, there are swirling whirlpools of light as iridescent as the morning sun. And there, in the center of this swirling, iridescent light, is an apparitional assemblage of memory’s artifacts: a summative review of a world full of lunatics and visionaries; bearded, pale, ugly, and howling like Lycaon in and about cemeteries and secret alley ways where cinematic entertainments, presented as flat trajectories, display a centrifugal cluster of vanities and illusions: partial caricatures in a pantomime of faces framed by other rotating faces, orbiting one another in soundless ellipses, subtly altered, yet with definable characteristics awash in a kaleidoscopic tableau of rainbow colors and liquid reflections. His weightless thoughts disentangle like so many strands of floating rope. Then, as quickly as they come, these thoughts begin to recede and to turn off as though, perhaps, the very stream of his existence was also receding, drying up, leaving not much more than a dry bed of pebbles; his essence reduced to the lowest common denominator. Why, even the outline of his body seems to blur, where once it was silhouetted against the backdrop of his small cell and infra dig of emasculating punishment, cut off irremediably from the world.

Slowly, he pushes himself up to the distinction of a sitting posture: his spine straight, his naked feet set flat upon the floor. He yawns a second time, emitting a loud onomatopoeia like a gunshot. Stretches his body. Smiles his smile. Begins to mumble-sing:

Oh the bells of hell go ting-a-ling-a-ling

And so pipes the piper as he pipes

Now les Demoiselles all lift their skirts

To dance the Stars and Stripes

***

Standing now, shoulders back, chest out, his posture suddenly droops forward with a sort of nervous obliquity. Then, quick-march to a corner johnnycan and ceramic sink, where he runs a trickle of cold, cinnamon water, and begins his morning rite of fundamental ablutions: Teeth. Hair. Vain expressions.

Feeling better, he lights a last cigarette, giving its ash an easy pell-mell flick, a sudden, surpassing blush darkening his narcotic expression of calm euphoria. The cigarette dangles from a pinched corner of his mouth. Smoke, like a dissipating vagrant spirit, rises and curls along the low ceiling, then through and out of the barred, broken window of easterly view.

***

Of course, there are windows, and there are windows:

Through one category of window one might, metaphorically speaking, survey selected phases and episodes of one’s own life: coming down with the chicken pox; having those nasty old tonsils yanked; losing one’s virginity; scoring a winning goal or touchdown; the death of a parent or sibling; graduation from high school or college . . .

Through a second category of window one may look out – oh, let’s say – upon the degeneracy, corruption (political, religious, social, etc. . .) and low-mindedness of the world.

And through a third category of window one may, perhaps, voyeuristically spy upon one’s neighbors; e.g.:

A man and a woman are seated on identical kitchen chairs, at a round kitchen table, in a square kitchen. The man has a penny-pale complexion. The woman, also, has a penny-pale complexion. Both the man and the woman are pale.

The man wears an expression of absentmindedness.

The woman wears a kind of gargoyle mask created with lipstick, powered rouge and mascara.

The man is dressed in a dark-colored overcoat (buttoned up to the collar), scarf, gloves, and hat.

The woman is naked, and one of her plump breasts is plopped into a milky bowl of porridge. With her two capable hands she lifts this breast out of the bowl of porridge, and begins to lick the nipple clean.

Suddenly, the man begins to sniffle and snort, like a pig at slop, laughing aloud at something he is reading in a newspaper – a newspaper that completely obscures him from the woman’s point-of-view.

Startled by this sudden cacophony of jollity, the woman begins to choke on a tasty lump of porridge; a moment later she slumps unconscious and not breathing onto the kitchen floor.

Hearing an uncommon THUMP! the man lowers his newspaper, and, seeing that the woman is no longer in her chair, across the table from him, he, as though calling to someone in another room, shouts out, “DO YOU NOT WANT YOUR PORRIDGE, THEN?”

***

With a sideways glance, he jealously surveys the escaping fume of smoke, a transient, gray shadow crossing his face; a face dimly blurred, yet ably reflected in the silver-drinking cup he now holds before him:

He has his late father’s hard eyes (so he has been told), and perfect fig nose (now no longer perfect, but broken and askew). Eyes, nose, he has even inherited his father’s optimistic delusions (this, too, he has been told), but definitely not the old man’s blind faith in holy writ superstitions and prayerful supplications. No, sir. Not that. He was no anointed communicant of the Holy Church of God-believing saints. He had not entered into the service of this or that orthodoxy: imparting, declaring a self-invented exordium of canard and fib to be preached throughout the land; hell, throughout the universe; even to where God hides and peeks at us from behind the planet Jupiter (as though even the planet Jupiter could hide God’s enormous head). (– Yes, God forgives us . . . but can we ever forgive God?)

There’s a sudden din of voices outside his cell. (Coming to take him away? His head on the block?) Now the metallic rattle of keys . . . the squeak of his cell door opening . . . swirls of electric light, temporarily blinding him. Two men enter.

The first man, wearing a plug-hat cocked jauntily on his bowling ball of a head, taps out a cigarette from a fresh pack.

The second man, a black halo above his head (this one could almost be the first man’s identical twin), carefully sets a tape recorder on the cell floor, and switches it on.

After pleasantries are exchanged, an arpeggiated stream of questioning commences: all part and parcel of his ongoing deanthropomorphization. Specific dates and times are spoken of: a minuscule of irregularities to be explained. Routine gobbledi-gookery. Nothing personal, Bub (May we call you “Bub?). It’s their job to weed out and to rid the world of its loathsome miscreants, scoundrels, and villains. – ‘Cause, ye see Bub . . . God, he don’t like miscreants, scoundrels, and villains . . . or Democrats.

The two men laugh.

When he speaks his voice is hoarse, yet scrupulous attention is paid to his humble emanations: each word, each groan, each pathetic sigh is recorded.

Who did he know? What did he know? Were there any notorious schemes a foot? Fodder for the glossy tabloids? Was he hoping for martyrdom? A medal? Some kind of promotion? His picture in the papers?

As time goes on the questioning gradually becomes more and more abstracted: What is good? What is evil? What is moral? What is ethical? What is reality? What is mind? What is thought?

Then it’s a series of: Complete the following sentences: Girls just wanna have ____________. The bigger they are the ___________. He who laughs last __________. What goes up, must ___________. Here today, gone ___________. Colder than a witch’s ___________. A penny saved is a ___________. To be or not ___________.

One of the two men gives him a drink of water, and places a half-smoked cigarette in his mouth.

Dear Jesus, why won’t they let me sleep? Hour after hour of this brutal insensitivity. What the hell time is it anyway? No light coming through the cell window. Middle of the night, no doubt: Zero Dark Thirty. Hello! Is anyone listening to me? Jesus? Pick up if you’re there, man. Screening your calls again, are you? Aw, c’mon, man, I’m dyin’ here! No? Okay. That’s cool, I guess. Anyway, sorry I missed you, man. Oh, it’s me, “Bub” by the way.

The two men say that they are satisfied. Yes, satisfied. One of them turns off the tape recorder. The other snuffs out a cigarette he has only half smoked. And then, with no further ado, they leave. Just like that.

The cell door, however, is left open.

***

He is lying on his narrow, rectangular bed, staring up at alligators hiding in the ceiling. At least he thinks they’re alligators. Granted, it’s not very likely, but you never know in such a damp climate.

Something he hears draws him suddenly to the cell window. Voices. He hears voices. Monotones and monosyllables. And the exultant chirping of discordant birds (well-hidden in the branches of precisely planted rows of trees) with their gliding chromaticism of fluted notes whistled rapid fire with incantatory repetitions, recalling a sweet oboe here, a soothing clarinet there, and always the gaiety of a conversing piccolo.

A spider at the edge of the window is sucking the juice from a fly it has captured. The fly is still alive.

With bedazzled eyes he searches like Joyce in his Martello Tower, and through the window he sees, below, a public garden with lush foliage. To the left of this garden he sees the dead wall of railway tracks where, on any given evening, one could, as a matter of course, find an omnium-gatherum of copulating, urinating, quarreling, bush-tailed johns and obliging cockchafers down on their knees. This eerie city scene (- Like some solemn fucking postcard, man!) is lighted by an electric streetlamp, and has the appearance of a black and white photograph by Brassai. Two men, Emerson and Thoreau, looking like Dean and Brando in black leather jackets, are chatting up a pair of Marilyn Monroe and Catherine Deneuve look-a-likes. Emerson and Thoreau are not who you think they are, but a plebeian pair of hooligans who happen to do a little pimping on the side. (Hey, a man’s gotta eat, don’t he?)

(Something must be living in his beard; suddenly he can’t seem to stop scratching. Goddamn squatters!!)

A fat doper is smoking a fat Moroccan reefer below an enormous billboard advertisement; this advertisement features a gorgeous young woman, in a wet tee-shirt, holding a bottle of a popular brand of beer.

And there’s a blind organ grinder and his monkey: the monkey holds a beggar’s cup in one of its hands, and wears a pillbox hat and a collar studded with tiny bells that tinkle like wind chimes as the monkey works a small group of gazing onlookers who are dropping coins into the cup. Suddenly two men in the group of onlookers are squabbling. There’s a punch to the nose, a knee to the groin; the crowd is growing like a tumor, cheering on the two men as they brawl. One man goes down. The second man viciously kicks him in the ribs. The man cries out. The crowd cheers, and is now calling for the man’s head: they want blood . . . a Niagara Falls worth. The organ grinder, too, has been knocked over, and his hurdy-gurdy stomped and smashed into kindling. But now the cops have arrived, and are questioning the two men; one of whom they put into the back of the squad car . . . and none too gently. Real brutes, these coppers.

But wait, there seems to be a discrepancy! No, it’s only a draft of cold air rippling into his cell. Nothing else. Yet the draft induces him to shiver as though he has just been touched with a shard of cold steel. And now, for the first time, he notices the cell door; that it has been left open.

Warily, he walks to the door. Stops. For approximately a full minute he stands still, not breathing, not taking his eyes off of the door. His heart, that perpetual engine of his continuity, is beating like a tom-tom.

Feeling a little woozy, a little light-headed, he backtracks to the bed, and sits down; but only for a moment. Soon he is up again and standing.

For a second time, he walks to the open cell door. On the point of walking through, he suddenly halts and stands frozen in place: a soldier at attention, in the throes of a chimerical fear. Had the door been left open purposely? Was this perhaps a devious trap? Or had the two men simply forgotten to lock it? No, that did not seem possible. Those men were pros, and pros do not forget to lock a cell door. That’s a given. Uncertainty now holds him in its grip as firmly as Menelaus once held Patroclus. The cold, dead silence of the cell enters into him, and once again he retreats to the bed. There he sits with his hands in his lap, his head bowed, eyes closed.

Then, lifting his head, he looks around his small cell, taking it all in, detail by detail, as though he was seeing it for the first time; but of course he is not seeing the cell for the first time, no, he is recalling his childhood home, seeing it and not his cell: the small bedroom he shared with his older brother, who was killed, blown to Kingdom Come, along with their parents.

Not very original, he thinks, all this dying; surely by now it’s been done to death! Of course all God’s creatures must die, and in the end we all come face to face with the inevitable nothingness. And we can thank first man Adam and his cunning cunt Eve for that!

This memory play evokes the whole stigmata of suffering he has known and endured . . . out there . . . in that world beyond his cell: that world where his own fate, his own demons lay in wait for him, as surely as death awaits us all.

But of course all that will come about later. For death is not likely to come today, or even right now. No. Now . . . now is Siesta-time.

Thus resigned, he lies back on the narrow rectangular bed, and stares up at the alligators in his ceiling. Soon he is asleep, with one skinny arm – the one with the zodiac tattoo of a fish on the wrist – extended limply over the edge of the bed:

Look closely now at this arm and you will see a thin, bluish vein pulsing menno mosso to a kind of legato spartplug music that only he can hear: just there, above the bearded, twitching thumb: one and two . . . two and one . . . and . . .

John Emerson’s works appear in Critical Quarterly, Tsarina, The Long Story, The Trunk, The East Hampton Star, Laundry Pen, Bathtub Gin, Caffeine, and Saint Ann’s Review. He was a writer-in-residence at Shakespeare and Company in Paris.