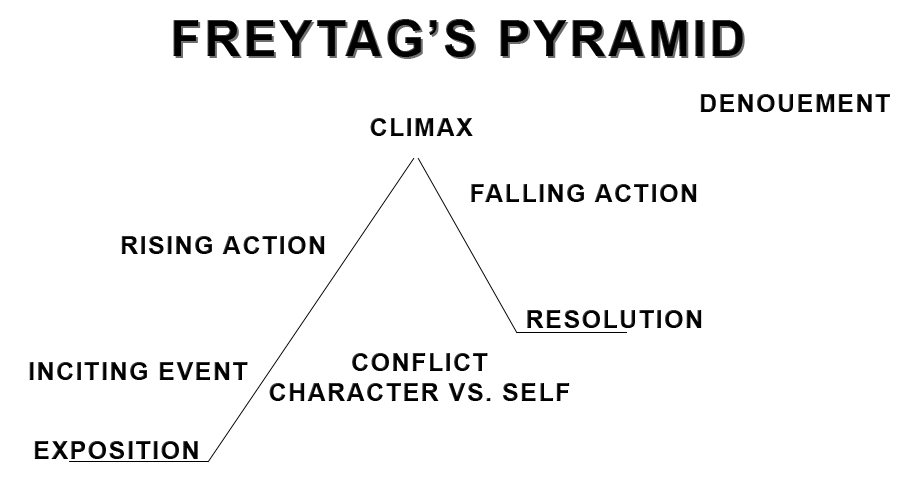

Dénouement is literally, ‘untying’ (as of a knot) in French; a plot-related term used in three ways: (1) as a synonym for falling action, (2) as a synonym for conclusion or resolution, and (3) as the label for a phase following the conclusion in which any loose ends are tied up [the ending resonance].” (Norton)

The Modernists secured a reader inspired dénouement, whereas, prior to this, authors would still, sometimes, write the dénouement as part of the narrative ending. Literary narratives will more often leave the dénouement to the reader, allowing for a more intellectually and emotionally imaginative experience following the close of a narrative.

Writing Dénouement

You will want to let your readers come to their own dénouements. Your job is to lay a foundation and developing structure with the details that will feed both an intended close and opportunity for readers to imagine their own individual and resonant dénouements.

If your closings tend to micromanage your readers’ resonating experiences with your works, try the following exercise. Choose a work currently in editing, one you would like to further explore especially in the closing. Study your current closing as if it were its own short short story. Copy it into its own document and revise it as such. Click here for exercises on short short stories. As you revise the closing into its own short short, let it guide you in terms of it’s intention, even if it derivates from your original intention for the closing and narrative in general.

Now, give this revised closing/short short story to three or more trusted readers and ask them to respond not only technically but also emotionally. What does this closing conjure for them once it is done?

With this new information, revise your new closing/short short story so to take full advantage of the feedback. Make sure to first focus entirely on the closing. Try to forget about the longer narrative and your original intention for this narrative. After you’ve given the closing focused attention, then reintroduce the closing into the longer narrative, weaving the new closing back through the narrative so that details build toward the closing. Make sure to spend focused attention on how the opening of the narrative and closing mirror and interact with each other. You might find that your opening will be entirely rewritten. You might find that much of your narrative is revised and/or even rewritten. This is okay. It’s part of the process. We spend so much time on the drafting of a new narrative that sometimes we forget or refuse to treat it as it is, a blueprint meant to be completely redesigned once the entire draft is complete.

Now, for the denouement. Study the last few paragraphs intensely and ask yourself this question: Are they necessary? This is a difficult question to ask as you’ve just spent so much time in crafting them, but truthfully, we often overwrite both our openings and our endings and often times the narrative will be better when cutting the extraneous. Think of it this way. In contemporary literature, readers like to be thrown into the narrative at the start, in medias res. It is not so different in the closing. Readers like to have room to linger on the narrative and when the writer gives too much direction at the end, it sort of siphons off the better resonance the reader might have had. This resonance, this denouement, is the crowning glory of your work. It is the finish of the “magic trick,” the prestige, and when done well, it gives the reader the lead.

Some writers might say, Okay, I’m in. Just tell me how to do it, as if there might be some sort of formula to the best closing and denouement. Honestly, some books will use a sort of formula (mystery, romance, crime, etc.) but even in formulaic genres, the better works will find their own individual patterns and flourishes. This is especially true in literary narratives. If you consider each literary work of merit as having it’s own “fingerprint,” then each opening, closing, denouement and all the rest of it will have it’s own organic patterns. The only way to find them is to write and rewrite and rewrite and revise… until the organic nature of the narrative reveals itself to the writer. There is no cheat code for this. No shortcut. It’s hard work and often frustrating. But stay with it and you will excavate the organic natures of your narrative, closing and denouement, and in these moments of discovery, you will find the artistic joy that drew you to writing in the first place.

Something encouraging: The longer you write, the more you will learn and develop your organic voice, patterns, flourishes…. It’s like a dancer learning the strengths of her body and of what she is capable. Once she learns this, she can enter each new dance with a level of self-knowledge and craft that allows her to focus on finding the organics of that particular dance. She already knows where she excels. You will find this same level of fluidity with your craft the longer you write and study your own writing. Once you’ve mastered “self,” you will then be able to master narratives and the art of dénouement with a level of confidence and craft that makes it more enjoyable and fluid. Again, the time and path you must take toward this will be specific to you. Stay with it. It will come.

Submit Your Work for Individualized Feedback

Please use Universal Manuscript Guidelines when submitting: .doc or .docx, double spacing, 10-12 pt font, Times New Roman, 1 inch margins, first page header with contact information, section breaks “***” or “#.”

Sources

The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present. Eric Kandel.

A Handbook to Literature

“Cogito et Histoire de la Folie.” Jacques Derrida.

Eats Shoots and Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation

The Elements of Style.

New Oxford American Dictionary

The Norton Anthology of World Literature

The Norton Introduction to Philosophy

Woe is I: The Grammarphobe’s Guide to Better English in Plain English

Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft

Writing the Other