The magnificent tree that we had admired for our more than twenty years in this house is now a stump after a week-long process of devastation, men with chain saws dangling from ropes in the upper reaches, the heavy thuds of dropping branches. It had been our favorite tree in the neighborhood, possibly the whole town, much taller than the others, perhaps one hundred and fifty feet high, and symmetrically ideal—an archetypal tree. Although we didn’t want to watch, we couldn’t help being aware of the pace of denuding, looking out to see lushness hewn, long leafless shafts. Why would anyone want to destroy such a beautiful thing?

Our neighbor had been eyeing that tree for fifteen years since the time he moved in. Now and then we had discussions of the property line and finally yielded, admitting that probably seven-eighths of the trunk existed in his yard. He won.

From the beginning we knew it would be useless to play the aesthetics card, though we did slip in praise of the tree now and then. Deaf ears. He clearly didn’t like trees, wasn’t moved by their grandeur. In fact, he had in his first years of residence removed a row of healthy, shorter trees from the back of his yard. Without the absorbing roots, he ended up with rainfall flooding his basement.

His apparent grudge against trees seemed to arise from complaints about leaves in his above-ground pool. We even had a brief row when he cut down a healthy twenty-foot tree on a border that was clearly half his and half ours.

But why the grandest tree in the area? We realized that leaves weren’t the real reason after his son asked us, “Aren’t you worried that tree will fall on your house?” We clearly weren’t, given the tree’s robust health and its distance from the building. Then my wife had an illumination. Our neighbor had grown up in a suburb on what had been the flat, potato farmland of Long Island. He wasn’t used to tall trees. They probably frightened him with nightmares of collapse. Living objects that loomed above him must have been sources of extreme anxiety.

Until her insight, I had never thought about such fears. Then I remembered an afternoon spent in Manhattan with a woman visiting from a European city free of tall buildings. Those skyscrapers frightened her. She kept her eyes to the pavement and avoided looking up.

It wasn’t until several years later that I learned she, as a child in the final months of World War II, suffered the bombing of her school by a strayed British airplane. The walls literally crashed down on her, killing a friend nearby and trapping her in rubble for many hours. How could she avoid nightmares of falling buildings?

I admire the Manhattan skyline from a distance. When walking through the concrete tunnels with the traffic and noise, wind and pollution, I can’t get a sense of the whole, can’t see above ground level. But I do like the views from upper stories or a rooftop. A friend once had a pied-à-terre high in a building on Eighth Avenue in the fifties, with a perspective down past the tip of Battery Park to the Statue of Liberty. That was the right way to see the city.

The same friend took my wife and me to Windows on the World, the restaurant at the top of the World Trade Center, where we could dine and gaze over the harbor. He ate there often, called the servers by their first names, and got special attention.

I thought of that place and those people on 9-11, when all that elegance and all those lives came crashing down in gray clouds of debris. Perhaps the visiting woman knew the possibilities much better than we.

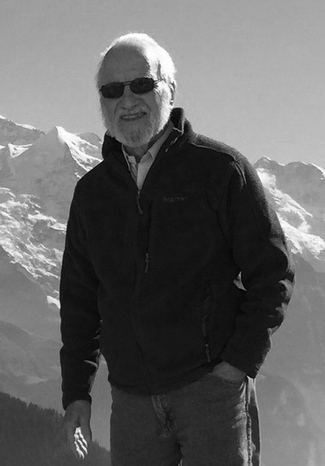

Still, I’m drawn to heights, though I was a bit apprehensive my first time up in a cable car suspended on a braided wire in the Swiss Alps. Watching the valley below, I contemplated the fall that would follow a snap, then took comfort in the reassurance that the entire contraption had been constructed by the same people who could make perfect watches. Once atop the peak of the Schilthorn Mountain, in the rotating Piz Gloria restaurant, I found myself rapt in looking out at the white crags of snow and ice that surrounded us. With great effort, humans had conquered some of the highest mountains in the world so that tourists like me could enjoy a hot meal and a view.

Yet it hadn’t always been that way for travelers. The Alps had been a source of terror rather than awe. The fears of those people were justified in the days of horses and hiking, considering the frequency of avalanches, rock falls, blinding snowstorms, and bandits. Many travelers froze to death. Beyond the actual dangers, superstitions invented witches, dragons, and alien species lurking in the jagged massifs. Some of those who had no alternative to journeying across the peaks asked for blindfolds to shut out the threats, both real and imagined.

Now the Alps are a playground, paradise for skiers and hikers in the snow. I recall once climbing up many icy steps, thinking we were alone in the vastness, and discovering a roomful of happy pleasure seekers in an inn alive with food, drink, and gemütlichkeit.

Certainly, avalanches still happen, rocks come roaring down, earthquakes tumble buildings, planes drop bombs, fall out of the sky, stormy winds topple trees. Yet we can’t wear literal or psychic blindfolds to shut out disaster. We can’t shrink every building, ground every plane, level every mountain, and cut down every tree, especially trees as glorious as the one we had looked up to for so long. We should thrive among all that is above us.

##