With her recent win of the Minnesota Book Awards for YA literature, Carrie Mesrobian has greatly contributed to the themes and emotional content found within Young Adult literature. Here, Mesrobian discusses different conceptions of what YA literature is and can be, how to bring emotional truths to the genre, what some of the newer trends are in the market, and how she addressed gender stereotypes in regards to trauma in her YA novel Sex & Violence.

With her recent win of the Minnesota Book Awards for YA literature, Carrie Mesrobian has greatly contributed to the themes and emotional content found within Young Adult literature. Here, Mesrobian discusses different conceptions of what YA literature is and can be, how to bring emotional truths to the genre, what some of the newer trends are in the market, and how she addressed gender stereotypes in regards to trauma in her YA novel Sex & Violence.

***

Q: When did you start writing YA, and what drew you to it?

Carrie Mesrobian: I started writing what became my first book, Sex & Violence, my first year in the MFA program at Pacific Lutheran University. I had intended to learn about fiction writing, and thought about writing mysteries, because I admire how clever they are and love to read them. I’m not a super deep philosophical person, either, so I didn’t have any issues with genre fiction or notions about writing “The Great American Novel” (also I don’t really like reading anything described as such.) But when I realized that I don’t really want to kill off people or research creepy ways to get murdered and the whole act of deception was kind of counter to my constitution, I gave up the mystery idea.

I teach teenagers about writing, so I always have lists of books they like, plus I’ve always liked reading books about teenagers and kids. (I have seen first-hand what Harry Potter and Twilight mean to both kids and adults and it’s beautiful and so important!) The idea that I’d write a book with a teenaged character happened as sort of a bratty response to reading a whole raft of YA books and being annoyed by what I was sick of seeing and what I wanted to see in these stories.

What draws me to YA is mainly that I’m a person who is still sorting over her coming-of-age years. They still matter to me, and in my head, I’m still wrestling with the same crap I wrestled with as a younger girl. I also have very little interest in writing what I know of from my current life, which is mainly the 3 M’s: marriage, motherhood, mortgage. That stuff is nice and I like my life, but I don’t find it a scintillating subject for fiction.

Q: What are some important tools to use or techniques to remember when writing YA? Are any of these different than what you would use when writing literature for adults?

CM: A basic premise I work from is that YA fiction is about adolescents, but it’s not necessarily for them. Because we know now that many adults read YA (and why wouldn’t they? They’ve been through that experience – why wouldn’t it remain fascinating?), so it’s best not to look at it as some kind of reading level or market (though agents/editors obviously look at that side of things). Interestingly, the Lexile reading level of my book is about 500, which translates to around 5th grade. However, a 5th grader probably wouldn’t get much out of Sex & Violence. So reading levels are not a useful metric, as they analyze vocabulary, mainly. The chief draw for YA is that the blowback from adolescence is something that most people wrestle with throughout their lives, though many people try to suppress and forget the awkwardness or the pain of those years (those people are often very snobby about YA lit in general, which makes me sad.)

Another thing to know is that YA is a big tent with many subgenres. There are people who only read fantasy or paranormal YA; some people prefer YA romance or YA science fiction, others are strict contemporary realism fans. The only thing all these stories have in common is that they are about the experience of adolescence and feature main characters who are adolescents.

With respect to craft, the elements of fiction are essentially the same as for any other fiction. But with YA, basically you’re drawing on the emotional truth you felt at that age, more than anything. That is what makes a YA story, I think, more than anything – it doesn’t have to be set in a high school or feature a prom scene or zits or any of those things.

However, though you are mining your own adolescence for this emotional truth, you do have to account for what’s happening NOW, which involves knowing and observing contemporary teenagers. One thing I got dinged on with my editor in revisions was the idea of porn magazines; these are not where anyone gets porn these days, though it was true of my growing up years. Now you can get porn on your cell phone. Stuff like that must be addressed if you are writing contemporary realistic YA fiction. Also, modern high schools can be extremely different places; class periods can be longer, student assignments look different, etc.

The main thing I see in weak YA fiction is nostalgia. By this I mean people writing about the adolescent years and then recounting a set a characters with the wisdom and experience they have now. A lot of this comes from good intentions – “I wish girls knew they had sexual agency and power because I never did!” – but the end result is usually something preachy or boring or a little too tidy. The idea that younger readers might “need” this or that “important message” is particularly annoying to me; younger readers are not some formless mass that literature is supposed to mold and mobilize. We don’t look at adult fiction readers like that, so why do we assume every goddamn thing kids might do must be wholesome or educational in some way? Just like adult fiction readers, younger readers deserve books where they see themselves and see others different from themselves. But everyone needs stories that are immersive pleasures, I think, regardless of age.

Q: What challenges might an author face if she wants to write for a teen market?

CM: You really need to be online, and especially Twitter. Not because teenagers are there; I don’t have a lot of teenagers who follow me online, nor do I care if they did. The reason you need to be online is because that is where your potential readers are, including teachers and librarians who make institutional purchasing decisions. This is where book bloggers hang out and agents who rep YA. You get a lot of information about where to target your queries or submissions to if you are following people on Twitter who are active in the YA or kidlit community. And it’s important to see what this writing community looks like, too. I guess it’d be like subscribing to journals, should you want to be a poet, you know? You have to read and follow the stuff your peers are reading and following and right now, a lot of that community happens online.

In terms of content, there used to be issues with writing about sex or abortion or drugs or other topics like that. For example, if a character used drugs in Act 1, then drug rehab must function as Chekhov’s gun in Act 3. Those kind of didactic “problem novels” we remember from the 70’s are pretty much over. Seeing consequences from bad choices isn’t required. So the sky’s the limit on content and I think that’s fair for the genre. Thinking in ‘shoulds’ or that ‘kids ought to know that…’ is pretty much doom for me in terms of a YA story. I’m very wary of people who say things like “think of the children!” As if all children lead PG-rated lives. As if teaching younger readers empathy by reading experiences unlike their own isn’t possible.

Also, what is on the shelf at Barnes & Noble is just a very tiny slice of this genre. What Barnes & Noble is putting on their shelves is fine but by no means represents YA. If you want an idea of how far this genre goes beyond ‘vampire romance’ or The Hunger Games, I’d suggest you talk to a Youth Librarian. What’s on the shelf is just the beginning and by no means is it the best of what’s available.

You also need to know the difference between Middle Grade Fiction and YA fiction. It’s not ALL Children’s literature; there are distinctions. An easy way to remember the distinctions is to think of Harry Potter. The first three books are middle grade novels – the fourth book is the bridge novel, from childhood to adolescence – and the last three are YA novels. The role of adult help comes into play in the first books, but is gone by the last few books, when Harry must fight Voldemort all by himself. Adolescence is very much about learning the limitations of adults while getting a sense of your own capacities. Additionally, in middle grade novels, there is generally no romance beyond a sweet kiss, while in YA novels, romance can be a substantial part of the story, as can sexual identity and experience. In middle grade novels, the kids are often reunited with parents or saved by helpful adults or they even save their own parents or families. In YA novels, the kids must save themselves (or not) and often leave or detach themselves from their families.

Q: How receptive were publishers/agents to the title Sex & Violence?

Q: How receptive were publishers/agents to the title Sex & Violence?

CM: The original title I sent out to my publisher and other agents was The Cupcake Lady of Tacoma. But my editor wasn’t a fan of that title, and perhaps that’s for the best. So, Sex & Violence was not my idea and was only meant to be a working title. But as my editor and I revised it, I got used to the idea and I could see how the two words kept ringing through the story. And then Meghan Cox Gurdon wrote this dumb piece in the WSJ about how “YA IS SO DARK OH MY GOD” and it was about how kids were doomed because there were too many dystopian stories or plots full of sex or featuring other horrible things happening to kids (because we all know that never happens in real life, right?) and I was like, “Fuck it. Let’s just call it Sex & Violence because that’s what we’re being accused of publishing, anyhow.” So we went with it.

Q: A main theme in Sex & Violence is learning how to handle trauma. How did you approach writing this in regards to a male character? Do you think there are different ways in which men and women are expected to deal with trauma? If so, how do you think gender expectations/stereotypes affect how one may reconcile with trauma?

CM: I think men are given very few routes when it comes to handling trauma. Their silence is required and their strength is assumed and that’s really about it. I think our society as a whole wants trauma survivors to shut up already, but I think women at least have the option of crying and talking about it with friends. Guys don’t really have that option. They can get really drunk, I suppose, or do other drugs, but that’s about it in terms of release. Going to therapy is shameful for many men, a sign of defeat. Guys are also not given many cues from their own fathers how to process their emotions in ways that aren’t harmful. They’re given anger or laughter and not much in between.

Q: What do you hope for teen readers to get out of this book? And adults?

CM: I hope they enjoy the time they spent in its 304 pages, mainly.

Q: You are currently working on a YA erotica piece. How do you go about that and what sort of boundaries do you need to keep in mind to both stay within and to break beyond?

CM: Oh, god. I guess the only boundary is what I’m willing to reveal! And that is how I write YA fiction, too. I never think – “I can’t go beyond these lines, it’s about teenagers.” So for that essay, too, I’m mainly just reckoning with what I want to make known about me. And trying to sort out what was going on in my head at the time, when I was 16, versus what I know now as a middle-aged woman.

Q: What other projects are you working on now?

CM: I just finished up copy-edits for my second book, Perfectly Good White Boy, which comes out in October. And I’m working on my third YA book, for HarperTeen. It’s also featuring a boy narrator and it’s about a kid who’s living between massive extremes of abundance and scarcity, as his parents are divorced and both live extremely differently in terms of wealth, both financial and emotional. That sounds really high-minded but it’s only because I don’t really know what I’m doing in that book yet. It takes me a couple of drafts to figure that stuff out. Also, it has no title. I think it’ll come out in 2015.

A native Minnesotan, Carrie lives in Minneapolis with her partner, Adrian, her daughter Matilda and her dog Pablo. debut young adult novel, Sex & Violence (Carolrhoda LAB) was named Best Teen Fiction of 2013 by Publishers Weekly and Kirkus, a finalist for YALSA’s 2014 William C. Morris Award for Debut YA Fiction, and a Minnesota Book Award winner for Young People’s Literature. Her second novel, Perfectly Good White Boy, (Carolrhoda LAB) will be released October 2014. She’s currently at work on a third YA novel for HarperTeen. You can follow her at www.carriemesrobian.com & on Twitter @CarrieMesrobian

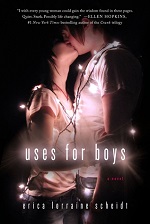

Uses for Boys by Erica Lorraine Sheidt

Uses for Boys by Erica Lorraine Sheidt Carrie Mesrobian teaches at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis. A native Minnesotan, she lives with her husband, daughter, and dog. Her work has appeared in Brain, Child magazine, the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, and Calyx. Sex & Violence, her first novel, was a finalist for the YALSA’s William C. Morris Award for Best Debut YA Fiction and a nominee for the Minnesota Book Award’s Young People’s Literature category. Her second novel, Perfectly Good White Boy, will be released from Carolrhoda LAB in October 2014. She is currently at work on a third novel for HarperTeen.

Carrie Mesrobian teaches at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis. A native Minnesotan, she lives with her husband, daughter, and dog. Her work has appeared in Brain, Child magazine, the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, and Calyx. Sex & Violence, her first novel, was a finalist for the YALSA’s William C. Morris Award for Best Debut YA Fiction and a nominee for the Minnesota Book Award’s Young People’s Literature category. Her second novel, Perfectly Good White Boy, will be released from Carolrhoda LAB in October 2014. She is currently at work on a third novel for HarperTeen.