Sarah Arvio’s night thoughts is a unique memoir told through poetry and notes in order to come to terms with past crises. The poetry makes tangible dreams Arvio had about past trauma, and in the notes section she discovers the meaning of those dreams. Not only is her poetry stunning, but the way in which Arvio navigates her past through the act of writing makes for a robust and outstanding text. Intrigued by the combination of using poetry to describe dreams and a notes section to reveal the power of dream interpretation, I asked Arvio some questions about the remarkable content of night thoughts, as well as her writing process behind it.

Sarah Arvio’s night thoughts is a unique memoir told through poetry and notes in order to come to terms with past crises. The poetry makes tangible dreams Arvio had about past trauma, and in the notes section she discovers the meaning of those dreams. Not only is her poetry stunning, but the way in which Arvio navigates her past through the act of writing makes for a robust and outstanding text. Intrigued by the combination of using poetry to describe dreams and a notes section to reveal the power of dream interpretation, I asked Arvio some questions about the remarkable content of night thoughts, as well as her writing process behind it.

Chelsey Clammer: night thoughts shows that writing can be about healing and reckoning. For you, what role has writing played in healing from trauma?

Sarah Arvio: I don’t know how many writers write to heal themselves; some write to reveal or to amuse. It took me a long time to heal from a trauma that occurred when I was a young girl. I went into analysis, I studied my dreams. I wrote notes–many notes, all for my own understanding. It wasn’t until years later that I wrote night thoughts. I had been intrigued by the dreams, and by exploring my mind and my past on the basis of those dreams; I wanted to describe the nature of that exploration. I healed first, and then I wrote night thoughts about that.

CC: The book consists of a sequence of dream poems, followed by notes exploring those dreams. What was your process in organizing the book?

CC: The book consists of a sequence of dream poems, followed by notes exploring those dreams. What was your process in organizing the book?

SA: I tried writing a prose book about my dreamwork. I found that I couldn’t make an ordinary narrative reflect the beauty, strangeness, and turmoil of the dreams–so I gave it up. A while later, I began writing out the dreams as poems. The Notes were an afterthought, a new layer of thought: in them I talk about the images in the dreams, and how they led me to memories. “Notes” is a misnomer: this is a narrative, made of accumulated notes, if you will, and it tells the story that gave rise to the dreams.

CC: Some facets of the book are unusually intimate and raw. What was hard about writing it?

SA: The dreamwork had been so rich, essential, and freeing; but I couldn’t describe it without telling my own story; invention was impossible. I worked to overcome my sense of shame; this was not easy. Ultimately, I yielded to an artistic imperative: these were the words that I had to write.

Some of the dreams and dream thoughts and real thoughts are shocking and even repellent. But thus are dreams, and thus often also is life. I tried to handle the upsetting elements delicately, that is, to show the inherent fascination of the image. Ugliness can be beautiful, as we know.

CC: What surprises came to you as you were writing out your dreams?

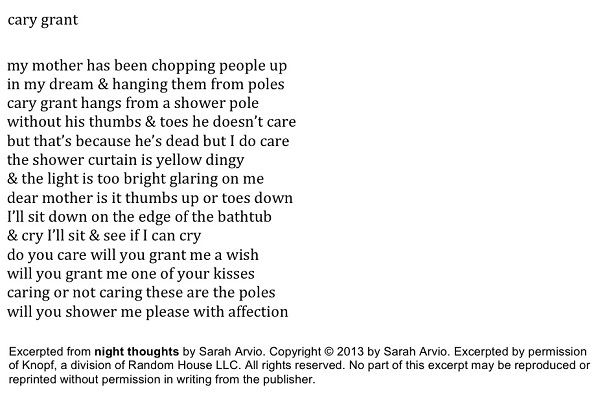

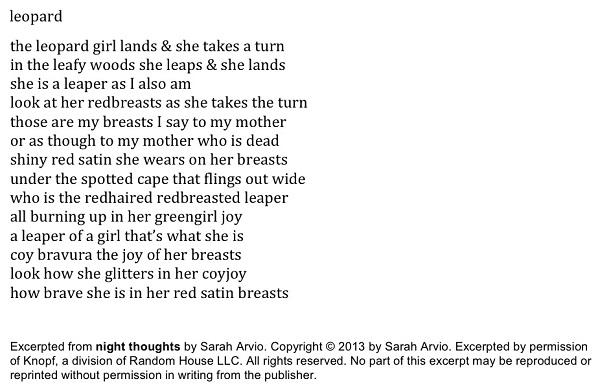

SA: I was astonished, again and again, by new folds of understanding, new associations, from the wordplay of the dreams. So, for instance, I had a dream in which my mother is cutting off fingers and toes, and she has hung Cary Grant from a shower pole. In the poem, the name turned into the words, “care” and “grant” and I understood why he was in the dream; as a riddle for these words about what mothers are supposed to do: care for you and grant you love. I just now thought of Grant and Hepburn in “Bringing up Baby”–the title of that film may have been one of the sources of my dream! Their “baby” is a pet leopard, however. It strikes me that I had another dream in which a leopard appears; my mother is in that dream, too.

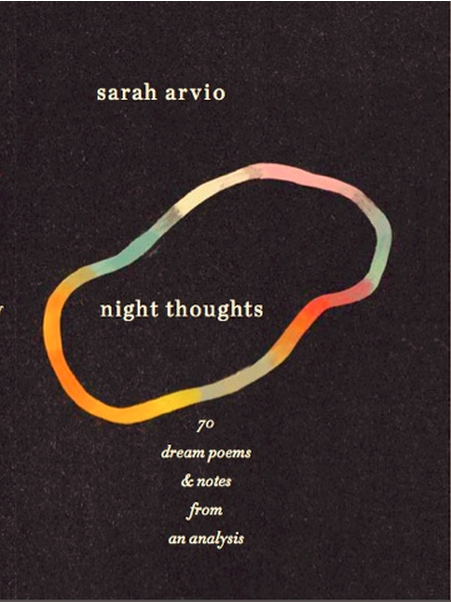

Sarah Arvio’s latest book is night thoughts: 70 dream poems & notes from an analysis, a hybrid work: poetry, essay, memoir. Her earlier books of poems are Visits from the Seventh and Sono: cantos. She has won the Rome Prize and the Bogliasco and Guggenheim fellowships, among other honors. For many years a translator for the United Nations in New York and Switzerland, she has also taught poetry at Princeton. She now lives in Maryland, by the Chesapeake Bay. http://www.saraharvio.com

Chelsey Clammer received her MA in Women’s Studies from Loyola University Chicago, and is currently enrolled in the Rainier Writing Workshop MFA program. She has been published in The Rumpus, Atticus Review, and The Coachella Review among many others, and has an essay forthcoming in the South Loop Review. She is an award-winning and Pushcart Prize nominee essayist. Clammer is the Managing Editor and Nonfiction Editor for The Doctor T.J. Eckleburg Review, as well as a columnist and workshop instructor for the journal. She is also the Nonfiction Editor for The Dying Goose. Her first collection of essays, There is Nothing Else to See Here, is forthcoming from The Lit Pub, Fall 2014. You can read more of her writing at: www.chelseyclammer.com.

Sarah Arvio’s latest book is night thoughts: 70 dream poems & notes from an analysis, a hybrid work: poetry, essay, memoir. Her earlier books of poems are Visits from the Seventh and Sono: cantos. She has won the Rome Prize and the Bogliasco and Guggenheim fellowships, among other honors. For many years a translator for the United Nations in New York and Switzerland, she has also taught poetry at Princeton. She now lives in Maryland, by the Chesapeake Bay.

Sarah Arvio’s latest book is night thoughts: 70 dream poems & notes from an analysis, a hybrid work: poetry, essay, memoir. Her earlier books of poems are Visits from the Seventh and Sono: cantos. She has won the Rome Prize and the Bogliasco and Guggenheim fellowships, among other honors. For many years a translator for the United Nations in New York and Switzerland, she has also taught poetry at Princeton. She now lives in Maryland, by the Chesapeake Bay.