Up on the mountain, we hang out in abandoned buildings, places where stories fill the holes in the walls. The old teepee was on the bottom of that ridge, before lightning struck. Now all that’s left is the charred platform. Harry’s cabin is up the road, but he sometimes returns, with his shotgun, his dogs, paranoia, so I stay away. The trailer sits low in the valley. With electricity, it’s the homiest of the buildings, half-wild, its library varied as the friends who’ve passed through: books on metaphysics, botany, geology, and astronomy; plus a bounty of porn and pine mice. The door’s unlocked, and some windows don’t close, but the vital mountain’s so gorgeous, it feels only natural to let it inside.

Above, atop the steep hill is the old silver bullet trailer, left alone and gone feral, which we took over and named The Witch’s Brew. Afternoons when the giant snowflakes whiten the forest, that’s where we hide out. We run an extension cord up from the trailer, and make coffee, music, and art from random junk. We’re real-life magicians.

Down the road, that’s the log cabin, with scalloped, golden pine walls, an iron wood-burning stove, and an unfinished roof that opens the attic to the stars and sky. Animals lived among the altar stones and carved chalices. We cleared them out and cleaned up, carried in water jugs, and sleep on the regal bed in sleeping bags.

On Halloween night, when the veil between worlds is thinnest, we drink lemonade and whisky with a new friend. The candles burn, pinon sap smolders sweetly on the stovetop, and our intimacies bind. We’re candid, affectionate, drunk, and Blacky confesses to horrendous teenage violence, says he’s been a bad person for centuries. Then we’re all remembering a ship from another life, in the 1800’s. Blacky was a pirate, and we were sailing passengers. He hugs my boyfriend tight, confesses, “I’m so sorry for killing you.”

His tattooed arms gesture my delicate Victorian gown; he says I’d looked so beautiful, he’d wished he were a different man. Blacky holds me, remembering across lifetimes. He stares at my lips, my eyes, says he’s ashamed for what he did to me. He’d hated himself for it. We all embrace, forgive, in the flame-lit cabin like a ship lost at sea.

At midnight, the three of us walk to a steamy meadow with protruding wooden posts. They’re next to the sulfur hot springs and fumeral, the last remnants of a 1920’s bathhouse and inn that burned to the ground decades ago. The moon shines white, cold, and huge. Then Blacky picks up a stake and starts bashing the old foundation posts. And it’s unlike me, but I pound the old wood too, breaking and splintering the pieces that remain, as destructive as time passing.

_

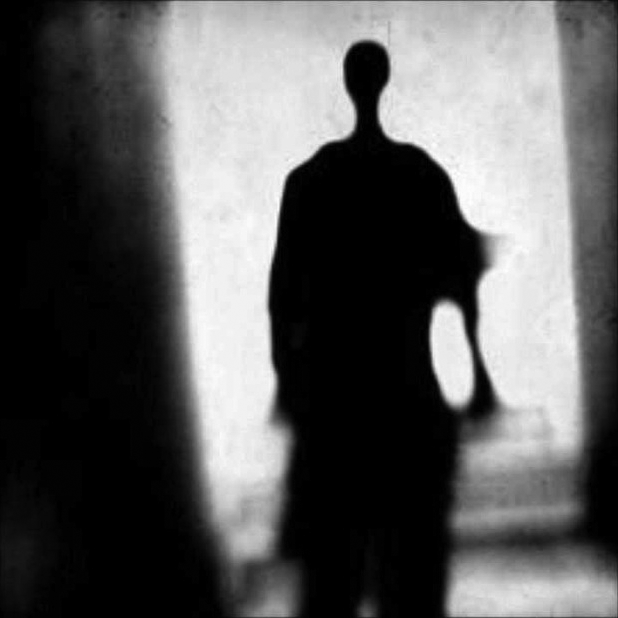

Editor’s Note: I chose “Sulfur Steam” because it sounds and looks like what prosetry could be. Simple. It’s a picture, a song, and a little story. Sperber describes nothing that’s in the actual DiClemente photo but still captures it. And mostly, I chose the piece because I couldn’t stop thinking about these people, at the end, fluidly and silenty sending pieces of wood flying out into the dark. (Vallie Lynn Watson, MMR Prosetry Contest Guest Editor)

Dawn Sperber’s stories have appeared in Annalemma, flashquake, Hunger Mountain, The Pedestal, and Rosebud. She has work forthcoming in Gargoyle Magazine, Third Wednesday, and Witches and Pagans. She lives in New Mexico, where she is at work on a collection of short stories and pursuing an MFA at UNM.

Vallie Lynn Watson holds a PhD in fiction writing from the Center for Writers, University of Southern Mississippi. She recently guest-edited the inaugural issue for Blip Magazine (formerly Mississippi Review online). Her manuscript, A River So Long, was first runner up in the 2009 Miami University Press Novella Contest. Excerpts from the work appear or are forthcoming in Pindeldyboz, Product, Journal of Truth and Consequence, Sunsets and Silencers, 971 Menu, Trailer Park Quarterly, Women Writers, Oracle, Staccato, Metazen and Ghoti. New fiction coming soon in Moon Milk Review.