MUSIC | Sam Pluta

For a number of years the central focus of my work has been on using the laptop, in combination with microphones, speakers, mixers, etc, as a performance instrument capable of sharing the stage with groups ranging from new music ensembles to world-class instrumental improvisers. I have done this by creating and coding software interfaces that create unique interactions with instruments and sonic spaces.

Both of the pieces below involve a piece of real-time software that I have coded to control feedback, and thus use feedback as a compositional tool. On paper this is a simple system. To get feedback, some output of the sonic environment is fed back into the system as input. This input is then output again and thus is part of the input again, etc, etc. In most cases the result is the undesirable sound of the microphone being too hot or too close to the speaker and exploding into one ear-piercingly intense tone that forces us all to cover our ears.

The single tone aspect of a feedback environment is important. This happens because the sonic energy of a signal gets built up around a specific frequency until that frequency dominates the sound. Once this pitch takes over the spectrum, there is no chance for any other pitch to take over, because all of the sonic energy in the signal is focused in one place.

However, as shown in Alvin Lucier’s classic work I am sitting in a room, sonic spaces reinforce many pitches, not just one. Essentially, the room is a filter that reinforces certain tones, causing them to be resonant, and weakens other tones, diminishing their audibility. In most feedback situations, the tone we hear resonating is likely the pitch most reinforced by the room (possibly altered by other factors, like where the microphone is in relation to the speaker).

However, because there are many pitches in any space, if one were to remove the most prominent feedback pitch from the space, a second pitch would rise up to take its place. If one were to remove that pitch, a third pitch would emerge. What my software does is allow, and in fact encourage, feedback to happen. At the same time, it listens to the sonic space and tries to detect if any single pitch has been feeding back for an extended period of time. If it has been, the software uses an fft filter to completely block that pitch. Because of the resonant quality of sonic spaces, a new pitch will then rise up and begin feeding back. The cycle can repeat forever, resulting in a beautiful cascade of tones that resonate with the room they inhabit.

American Idols

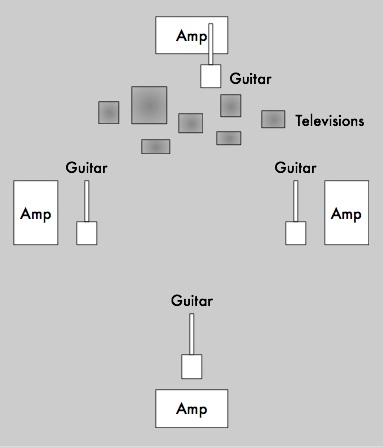

What I realized in working on these two compositions is that the “filter” part of the feedback system, which is usually a room, could be anything in the circuit between the microphone and the speaker. In American Idols, the filter of the room is replaced by four electric guitars. These four guitars are each facing an amplifier, and thus causing the feedback situation. The sound leaves the speaker, vibrates the strings on the guitars, the vibration of which in turn goes out the speaker. The guitars will not feed back at any pitch. Rather, they only resonate at pitches that are found on the open strings – ie, the harmonic series of each guitar string. Therefore, in American Idols, the guitars are tuned to pitches which are part of one harmonic series, more specifically the series of 60hz, which is the series that guitar amplifiers will buzz at when plugged in and turned on.

[vimeo width=”600″ height=”365″ video_id=”36673451″]

The guitars are arranged in a square around the installation space; one behind the televisions, one on the opposite wall, and two on either side. This creates an all encompassing surround effect that engulfs the audience and fills the space with sound. In addition to the sonic element in this piece, there are 12 televisions at the front of the exhibit. I send the four audio signals from the guitars directly into the televisions, causing them to display an image which corresponds nicely to the beautiful microtonal drone simultaneously occurring in the space.

Broken Symmetries (or the Masses of Gauge Bosons)

Broken Symmetries is a kind of installation/concert work, which creates a sonic environment for the audience to live in. This piece also uses my feedback control software as its foundation. This time, instead of guitars, however, I use a bank of resonating filters tuned to the harmonic series of the open strings on a violin. Because the sound travels out of the speaker and into the space (before it is picked up by the microphone), the room acts as an additional filter. I was originally going to use guitars, but the guitar feedback only works at high volume levels, and I wanted to have more dynamic control during this performance.

As seen in video, the speakers for feedback are set up behind the performing ensemble. The feedback presents a backdrop for the group, which layers over the top with cascades of sound. The piece begins with a substantial microtonal violin solo, performed beautifully here by Joshua Modney. The feedback begins about half way through the violin solo and the ensemble enters about seven minutes in. The following performance features the Wet Ink Ensemble – Joshua Modney (violin), Erin Lesser (flute), Alex Mincek (tenor saxophone), Eric Wubbels (piano), Ian Antonio (percussion), and Sam Pluta (electronics).

[vimeo width=”600″ height=”365″ video_id=”56873139″]

This is part of a series of musician essays collected by Joseph Di Ponio.

Sam Pluta is a New York City-based composer, improviser, and sound artist. Known internationally for his laptop performances with groups like Rocket Science, Wet Ink Ensemble, and The Peter Evans Quintet, he is widely regarded as one of the most compelling electronics performers of his generation. He has performed as a laptop soloist and chamber musician at the Lucerne Festival, the Donaueschingen Festival, the Moers Festival, Bimhaus, Porgy and Bess, and the Vortex, amongst other international concert venues and festivals. As a composer, he has been commissioned and premiered by Mivos Quartet, Yarn/Wire, ICE, Timetable Percussion, RIOT Trio, So Percussion, Dave Eggar, and Prism Saxophone Quartet. He is Technical Director for Wet Ink Ensemble, a new music group dedicated to promoting music by young composers. A devoted pedagogue, he directs the Electronic Music Studio at Manhattan School of Music, teaches at the Computer Music Center at Columbia University, and is Academic Dean and Director of Electronic Music at the Walden School, a summer music program for young creative musicians. Sam’s music is released on quiet design and Carrier Records, a record label he runs with Jeff Snyder and David Franzson, and his performances can also be found on More Is More, Tzadik, and hat[now]ART. Sam holds a Doctorate in Music Composition from Columbia University and additional degrees from UT Austin, the University of Birmingham (UK), and Santa Clara University.

MUSIC | Joseph Di Ponio

I am happy to have been appointed as the music editor for the Dr. T.J. Eckleburg Review. In the coming months, I will post bi-weekly music of a variety of styles, as well as writings about music, in the hope of illustrating the great diversity that can be found in Western music derived from the classical tradition in the early 21st Century. While this music tends to be termed “Contemporary Classical,” or “New Music,” “Contemporary Music” and even (still) “Avant – Garde,” all of these monikers prove to be problematic. At best, these terms are inaccurate (take, for instance, the oxymoronic nature of Contemporary Classical) and at worst, off-putting and elitist. Even the phrase that I used to describe what I will be presenting in the journal (“Western music derived from the classical tradition in the early 21st Century”) is, admittedly, not only cumbersome but also exclusionary to a large degree. Terms like these immediately place a value on the work that serves only to separate it from other genres namely pop, jazz, rock, and even the equally problematic field of sound-art. While this may seem only to be an issue of naming, it can help to explain the unique predicament of contemporary composers and the performers who make these works audible.

I am happy to have been appointed as the music editor for the Dr. T.J. Eckleburg Review. In the coming months, I will post bi-weekly music of a variety of styles, as well as writings about music, in the hope of illustrating the great diversity that can be found in Western music derived from the classical tradition in the early 21st Century. While this music tends to be termed “Contemporary Classical,” or “New Music,” “Contemporary Music” and even (still) “Avant – Garde,” all of these monikers prove to be problematic. At best, these terms are inaccurate (take, for instance, the oxymoronic nature of Contemporary Classical) and at worst, off-putting and elitist. Even the phrase that I used to describe what I will be presenting in the journal (“Western music derived from the classical tradition in the early 21st Century”) is, admittedly, not only cumbersome but also exclusionary to a large degree. Terms like these immediately place a value on the work that serves only to separate it from other genres namely pop, jazz, rock, and even the equally problematic field of sound-art. While this may seem only to be an issue of naming, it can help to explain the unique predicament of contemporary composers and the performers who make these works audible.

The predicament of naming is a relatively new problem that could only have occurred during a time of stylistic surplus. The second half of the 20th Century was an incredibly self-conscious era, especially in the United States, where the debate between the serial avant-garde and other emerging genres became so heated that the divisions that were created allowed for little productive discourse about what the music was actually doing. As John Cage once mentioned in the 1960s, we can characterize much of the 20th Century as being preoccupied with dividing up the acquisitions of Schoenberg and Stravinsky. This preoccupation became manifest with a concern for musical structure on the one hand and intuitive composition on the other. In either case, the need to self-identify as a certain “type” of composer often superseded aesthetic identity. Still, this ideological rigidity also symbolizes the breakdown of the Modernist ideal that privileged the new and forward looking, and signals, in some ways, the death of the Avant-Garde.

This breakdown can be heard quite readily in the music of George Rochberg (1918-2005). A quick comparison of his “Duo Concertante” from 1955 and the third movement of his sixth string quartet composed in 1978:

Rochberg – “Duo Concertante”

[youtube width=”600″ height=”365″ video_id=”2nA5_KRt5m0″]

Rochberg – “String Quartet No. 6, Movement III”

[youtube width=”600″ height=”365″ video_id=”4xf9_JYLQvA”]

The first example illustrates Rochberg’s early interest in tightly structured atonality while the other shows his break from this aesthetic. The fact that he chose to base the 6th Quartet on something as tired and overplayed as Pachelbel’s “Canon in D” (now heard everywhere from television commercials to New Age recordings) is an acknowledgment, of sorts, that the classical avant-garde had run its course. Likewise, Sofia Gubaidulina’s violin concerto “Offertorium” (1980) is an acknowledgment of the trajectory of western music. Based on the theme from J.S. Bach’s “Musical Offering,” she contrasts dense, highly dissonant textures with melodies that emerge and then quickly recede into the background almost as if they are being concealed by their own sonic history.

Gubaidulina – “Offertorium”

[youtube width=”600″ height=”365″ video_id=”0yEQLKycpew”]

We now live in a time where composers reap the benefits of the breakdown of the avant-garde. The arguments are often no longer about technique or the merits of consonance versus dissonance but about sound itself. There is great stylistic diversity among composers who have been finding their voices between the last decade of the 20th Century and the first decade of the 21st. The concern now is not necessarily about finding a new technique in order to produce a new sound but a focus on the sound itself. And perhaps more importantly, we openly acknowledge the great diversity of the music we grew up with as well as our place in the history of Western classical music.

Joseph Di Ponio is a composer of acoustic and electronic music currently living in New York City. In general, his work is concerned with issues being and temporality, and is influenced greatly by contemporary thought on the phenomenology of time and being. Joseph received his Ph.D. In music composition and theory from Stony Brook University (SUNY) with a secondary area in art and philosophy.