The villagers heard the stickman coming before they saw him: hiss on the gravel road into town, the click and clack of branch to branch. He walked up the dirt street dragging bundles of wood and brier behind him. The stickman was twice as tall as the tallest man in the village and wore a cloak of brown leather, so patched it looked made of mouse skins. He was filthy and thin, vermin walking the blades of his straw-yellow hair and beard.

The stickman sat down against the side of Nye’s dry goods store and began twisting and snapping his branches. The villagers came out to look. They’d never seen anything like him. Nye felt sorry for the stickman and asked him if he was hungry. The stickman kept twisting sticks in his long fingers. She brought him bread and put it in his lap. He ate it while they tried to get him to talk and wondered where he came from. Had the villagers left him alone, the stickman probably would have left. But they fed him, and because they fed him, he stayed.

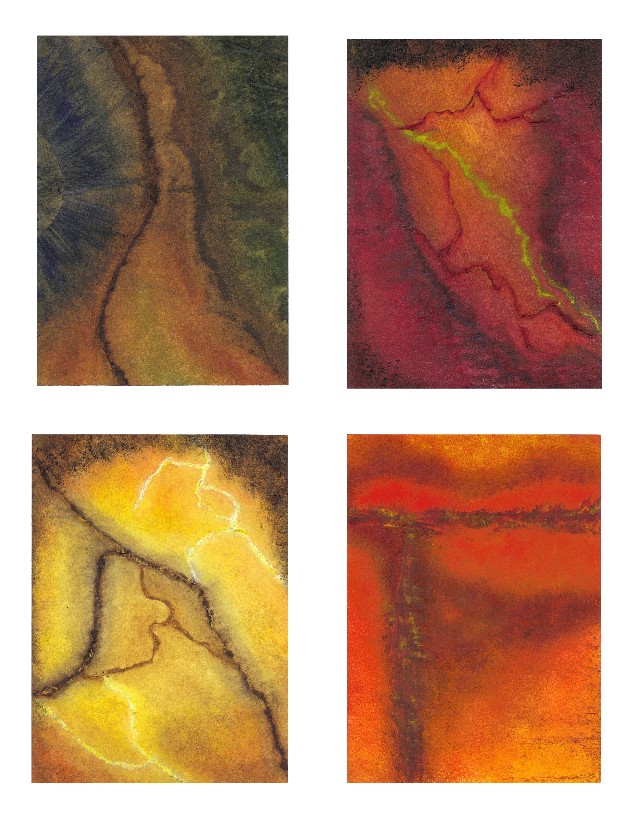

The next morning, the stickman had made tiny globes of knitted branches and twine and placed one in front of every door. Inside each was a songbird, trilling mournfully. The villagers picked up their globes and stuck their fingers inside to brush the bright feathers. The birds panted and thrashed against the sides, loose feathers collecting in the bottom of the cage. The villagers laughed at the birds for being so afraid, and agreed that the cages were beautiful. Nye embraced him, startled that a body could be so hard and coarse, like a tree. Maybe then the stickman would have left. But they praised his cages, and because they praised him, he stayed.

All night, the villagers lay in their beds and listened to the warp and snap of branches. They heard the heavy tread around their doors and saw the stickman’s shape blacken their windows as he walked by. They wondered what beautiful things he’d have for them in the morning.

The next morning, Nye found her four cats rolling around on the porch inside globes of twisted branches. They saw her and ran to her feet, bumping the wood against her shins, meowing and clawing at the sides. Nye laughed at the stickman’s joke. Outside, the other villagers found dogs, pigs, and chickens all rolling across the dirt in their round wooden cages. They laughed, but when the villagers tried to break them open, they couldn’t. The branches would bend when twisted, but always bounce back to shape. They were too hard to saw through. The carpenter shook his head and said that they were clever things. While they talked about it, a boy rolled into the street in his cage, looking out at them through the bars. Everyone was quiet.

They found the stickman outside the village twisting together huge cages, bigger than any of the others. They couldn’t make him understand that they wanted him to let the boy go. Nye picked at a half finished cage, and a pair of branches slid apart and sprang open toward her. She tried to fix it, but couldn’t. The stickman kept working as though no one was there.

The villagers spent all afternoon working on the boy’s cage with axes, knives, and metal bars. Nothing worked. The father told the boy to press himself to the back of the cage, then touched a flame to the thinnest branch. The fire caught and swept over the globe, soaking it in flames. The branches bent but did not break as the father shook them, burning his hands. Afterward, everyone said that the boy had not screamed. The flames died out eventually, only ash and bone inside. The cage was blackened, but whole. The carpenter shook his head and said that they were clever things. Nye pulled the bones out of the cage, and they buried them. The villagers came to the stickman again. They told him that he would have to leave and take his cages with him. Smiling, he kept working on his row of giant cages.

That night, the villagers dreamed they were up high in a tree and couldn’t climb down. While they dreamed, the stickman went to every window, leaned inside, and gathered the sleeping villagers in his arms. They awoke the next morning in round cages, the sun fractured through the wall of branches in front of them. Nye saw that the inside of the cage was lovely, the wood gleaming and white, the weave seeming to have no beginning or end. She found strange writing carved all along the inside and ran her finger over it, wondering what it meant.

The villagers were afraid. They shouted for the stickman to let them go. He tipped their barrels of rain water into the dirt street, turning it to mud. He rolled the wooden globes, airy and light, through it until they were coated, the mud dripping down through the gaps and soaking the villagers. Then he pushed them through the stables until they were covered in straw. The villagers lay in the egg-like dark and said nothing, their ears pressed against the damp walls listening.

Outside, the day was bright and green. A wall of wind came from the east and started the cages to rolling. The stickman led his cages to places none of them had been before. Inside her globe, Nye saw a gap in the wood, the place where she’d undone the branches the day before. She pushed against it, and the side of the cage opened and split. Nye shoved her body through, dried chips of mud falling like egg-shell, and fell out on the ground.

Her cage tumbled faster without her, catching up to the stickman in front. He did not look back at her. The stickman climbed inside Nye’s broken cage and started knitting it back together from within. The globes whispered over the grass and rushed away. Nye ran after them to help the others, but they were too fast and disappeared over the hills.

Nye looked for the stickman and his cages for years, wandering into lands she’d never heard of. The people there spoke languages she couldn’t understand, and eventually she gave up trying to speak to them at all. Her clothes wore thin, and Nye patched them with whatever she could find. She collected fallen branches and vines from the woods, dragging them behind her into villages. These, she twisted into small globes and gave to people, hoping that they would recognize them and point her in the direction of the stickman and everyone she loved. They were delighted, but did not understand. She slept in the shade of their houses, and they brought her bread. Sometimes, she left the small globes on their doorstops out of gratitude. Sometimes, birds would perch on them and fall inside, getting trapped. Nye picked up her sticks and headed to the next town, sure that she was getting closer.

Micah Dean Hicks is a master’s student in the Center for Writers at The University of Southern Mississippi. His work is published or forthcoming in over twenty publications, including PANK, kill author, Prick of the Spindle, Tryst, and Brain Harvest.