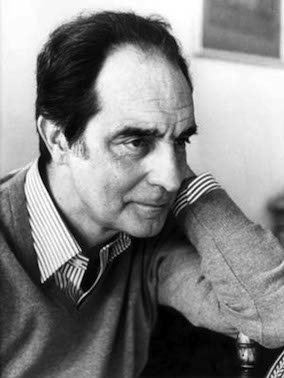

Born: 15 October 1923

Died: 19 September 1985

Little known facts:

The first thing Calvino ever published was a drawing that appeared in a magazine published by a drawing correspondence school; he was their youngest pupil at eleven years old.

The dense forests and abundant fauna in Calvino’s early fictionderived from a small working farm on which his father pioneered the cultivation of what were then exotic fruits.

Much better known facts:

Italo Calvino was born in Santiago de Las Vegas, a suburb of Havana, Cuba in 1923, the son of two Italian agronomists.

Calvino’s mother encouraged both Italo and his younger brother to join the Garibaldi Brigades, a clandestine Communist group fighting the Germans in WWII.

Italo Calvino was an Italian journalist and a writer of short stories and novels, best known for his trilogy Our Ancestors (1952–1959), his collection of short stories Cosmicomics (1965), and novels Invisible Cities (1972) and If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler (1979). While Invisible Cities, a collection of poems in prose, was more successful in literary circles, Italian Folktales was a public success in the U.S. where his image has been that of a writer of tales and fantasy.

Two years after Calvino’s birth, his family returned to Italy, settling in San Remo on the Ligurian Coast where his father directed an experimental floriculture station. They also had a country house in the hills, where Calvino’s father actually developed the techniques for growing grapefruit and avocados. In that environment, Italo admired Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book and developed early interests in drawing and in stories—much to the dismay of the two scientists who had brought him into the world.

Italo studied in San Remo and enrolled in the agriculture department of the University of Turin to satisfy his parents. Calvino transferred to the University of Florence in 1943 and reluctantly passed three more exams in agriculture. By the end of the year, the Germans had occupied Liguria. At twenty years old, Calvino refused military service and went into hiding. He reasoned that, of all the partisan groups, the communists were the best organized, and in the spring of 1944, he joined the Garibaldi Brigades, fighting in the Maritime Alps until 1945. Years later, he said politics was necessarily the first phase of his adult life and it held great importance for him because of the traumas involved in surviving the German occupation.

After the war, Calvino began writing about his wartime experiences. He published his first stories after resuming his studies and shifting his focus from agriculture to literature. During this period, he wrote his first novel, The Path to the Nest of Spiders and had already started working for his publisher while he finished his degree.

In this postwar period Calvino joined the Italian Communist Party but soon began to feel increasingly that “the idea of constructing a true democracy in Italy using the model—or myth—of Russia became harder and harder to reconcile.”

In 1952 he produced a novella, The Cloven Viscount that appeared in a series of books by emerging writers called Tokens. Reviewers outside the Party had praise for the work, but his departure from his initial realist style garnered criticism from within the Party. He resigned from the Party in 1956 when the Soviet Union invaded Hungary.

Calvino published a collection of Italian folktales in 1956 and the next year brought out The Baron in the Trees. In 1959 he published The Nonexistent Knight. These two combined with The Cloven Viscount are found today in the volume Our Ancestors. In 1965 he published Cosmicomics, and in 1979 he published his novel If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. The last works published in his lifetime were a novel Mr. Palomar (1983) and a collection of stories Difficult Loves (1984).

The range of Calvino’s literary production displayed a highly versatile capability to write as a neo-realist and to transition to post-modernist with varying degrees of movement through fabulism to fantasy. He became a well-respected post modernist, declaring that his central theme was the “conflict between the world’s choices and man’s obsession with making sense of them.”

One of his better examples anthologized in English is “The Distance of the Moon.” It is a tale that begins with a premise that a theory about the Earth and the Moon once being very close (attributable to British astronomer and geophysicist George H. Darwin) was in fact true many years ago. The fantastic component involves the people existing at the time, complete with economic motives and organization, with longings for people and things (many unattainable), and choices that had to be made by them as they recognized the Moon was easing away from the Earth. The narrator was a participant and is still trying to make sense of the choices people made at the time. Besides that set of considerations, the reader will find the source of the title of The Moon Milk Review—the predecessor to The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review.

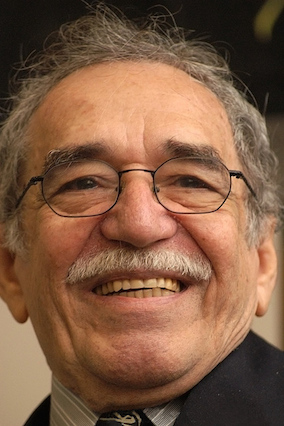

In a collection of his published and unpublished essays produced after his death and at the close of the century, the frame for his major body of work is partially revealed in the discussion of his admiration and his debt to Jorge Luis Borges. Calvino’s initial affinity for Borges centered on the notion that literature is a world rendered and governed by intellect that should “provide us with the equivalent of the chaotic flow of existence, in language, in the texture of the events narrated, in the exploration of the subconscious”—located exactly in the heart of the fin d’ siècle emphasis in art, literature, and science emanating from Vienna into the Western world as detailed by Kandel in The Age of Insight.

Calvino explains “the Borgesian continuity between historical events, literary epics, poetic transformation of events, the power of literary motifs, and their influence on the collective imagination.” However, he points out that within this construct, we must keep in mind “it is in the rapid instant of real life, not in the fluctuating time of dreams, not in the cyclical or eternal time of myths, that one’s fate is decided.” He says the real impact of a literary piece or tradition is on the collective imagination that resides in the subconscious and the conscious mind—for an individual to draw from when looking for a code or a standard by which to make decisions.

During the summer of 1985, Calvino developed a series of notes on literature for the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard University in the fall of that year. However, Calvino was admitted to the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena on 6 September, where he died during the night of the 18th of a cerebral hemorrhage. His Harvard lecture notes were published posthumously in Italian in 1988 and in English (as Six Memos for the Next Millennium) in 1993.

His American reputation began when Gore Vidal described all of his novels as of May 30, 1974 in The New York Review of Books. He was the most-translated contemporary Italian writer at the time of his death, and a celebrated contender for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

A FEW OF ITALO CALVINO’S QUOTES

“Only a certain prosaic solidity can give birth to creativity: fantasy is like jam; you have to spread it on a solid slice of bread. If not, it remains a shapeless thing, like jam, out of which you can’t make anything.” — From an Italian television interview shown after his death, quoted by Gore Vidal

“The contradiction [trying to use Russian model to reshape Italy] grew to such an extent that I felt totally cut off from the communist world and, in the end, from politics. That was fortunate. The idea of putting literature in second place, after politics, is an enormous mistake, because politics almost never achieves its ideals.”

A FEW QUOTES ABOUT ITALO CALVINO

“He has a scientist’s respect for data (the opposite of the surrealist or fantasist). He wants us to see not only what he sees but what we may have missed by not looking with sufficient attention.” — Gore Vidal

“Calvino was a genial as well as brilliant writer. He took fiction into new places where it had never been before, and back into the fabulous and ancient sources of narrative.” — John Updike

ITALO CALVINO’S NOTABLE WORK

The Baron in the Trees(1957), Invisible Cities (1974), If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler (1979), Six Memos for the Next Millennium (posthumously)

ITALO CALVINO’S AWARDS

Asti Prize 1970

Feltrinelli Prize 1972

Honorary Member of the American Academy 1975

Austrian State Prize for European Literature 1976

French Légion d’honneur 1981

SOURCES

Italo Calvino. Difficult Loves (trans. William Weaver). San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1958.

Italo Calvino. Why Read the Classics? (trans. Martin McLaughlin). New York: Pantheon Books, 1999.

Gore Vidal. “On Italo Calvino,” The New York Review of Books, November 21, 1985

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1985/nov/21/on-italo-calvino/

Italo Calvino, The Art of Fiction No. 130 Interviewed by William Weaver, Damien Pettigrew http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2027/the-art-of-fiction-no-130-italo-calvino

Eric R. Kandel. The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain From Vienna 1900 to the Present. New York: Random House, 2012.

Richard Perkins is a regular contributor to The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review and a graduate of The Johns Hopkins University MA in Writing Program. He is writing an historical novel and revising a collection of connected stories.