One is not born, but rather becomes, woman.” —Simone de Beauvoir

One is not born, but rather becomes, woman.” —Simone de Beauvoir

The Abridged Feminist Biography of Simone de Beauvoir with Cameos by Jean-Paul Sartre and Other Men

Simone “le castor [the Beaver]” de Beauvoir was born in Paris, France, in 1908. When she was twenty-one, she went to the Sorbonne to study philosophy and the art of sexual politics with her contemporary, Jean-Paul Sartre. “She was the youngest agrégée in French history,” taking second in exams only to Sartre’s first place. There is ongoing speculation as to who truly deserved the first place, but she continued to have sex with Sartre anyway. She even had sex with the people he was also sexing. It can be agreed by many scholars and critics that Beauvoir had a lot of sex.

In 1943, she saw published her first major work, a novel titled She Came to Stay. She dedicated the novel to Olga, a seventeen-year-old protégé with whom she was having sex and Sartre wanted to have sex but was rejected by young Olga and so he seduced and had sex with Olga’s sister, Wanda. A side note, for kicks: At the end of She Came to Stay, “the Beauvoir character murders the Olga character” (Menand).

For many years, Beauvoir continued to have sex with many people, not so much Sartre, anymore though, they wrote many letters back and forth about the sex they were having with other people and the sex they imagined with other people. At some point, Beauvoir was dismissed from her teaching for having too much sex and writing about sex and socialism and women and equality and incomes of their own. The Nazis did not like her. Thankfully, neither the Nazis nor academia dismissed Sartre for having too much sex or socialism. That, of course, would have been ludicrous.

In 1949, Beauvoir saw published The Second Sex, written while Sartre was in a relationship with his latest lover, Vanetti, a French woman living in the US and to whom he proposed marriage. According to Louis Menand in his New Yorker article, “Stand by Your Man: The Strange Liaison of Sartre and Beauvoir,” this did not please Beauvoir, even though she was already having sex with Nelson Algren. Menand speculates that Sartre’s proposal to Vanetti was a “final push” against Beauvoir’s femme sensibilities, even though, Beauvoir had already rejected Sartre’s marital intentions years ago. An ongoing debate. The first US translation of The Second Sex was in 1989 by Howard Madison Parshley, a zoologist specializing in entomology and an avid fan of Beauvoir’s original text, though, his 1989 translation receives continued criticisms from Beauvoir academics as having cut too much of the text and leaving out too many female writers and their original citations. In 1983, “Margaret Simons informed [Beauvoir] . . . of the specific changes in the American text [and] Beauvoir responded . . . ‘dismayed to learn the extent to which Mr. Parshley misrepresented me'” (Gilman).

The Second Sex was criticized as pornography and placed on the Vatican’s list of forbidden texts, but nonetheless, became a bible of modern feminism. Four years after the first publication of Second Sex, a not-so-good translation appeared in the states. In 2009, “a far-more-faithful, unedited English volume was published, bolstering Beauvoir’s already significant reputation as one of the great thinkers of the modern feminist movement,” (Biography) sex and all.

Beauvoir was a preeminent thinker, writer, modernist feminist, a French resistance fighter, a U.S. Vietnam policy condemner, an abortion rights and women’s equality activist, and yes, she was a woman who had sex.

She died in 1986 and now shares a grave with Sartre in the Montparnasse Cemetery. Let’s just reflect, for a moment, on this.

In her fierce intellect and courage, we find in Simone de Beauvoir’s philosophies and actions not only the feminist ideals of the twentieth century but also ongoing gender ideologies to come. Let us end on perhaps her most famous words, On ne naît pas femme: on le devient. “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman” (2009).

The Second Sex: On ne Naît pas Femme: On le Devient

“One is not born, but rather becomes, woman” (2009).

“One is not born, but rather becomes a woman.” (1989).

In the 2009 translation of The Second Sex, the translators address la femme in the “Translator’s Note”:

One particularly complex and compelling issue was how to translate la femme. In Le deuxième sexe, the term has at least two meanings: “the woman” and “woman.” At times it can also mean “women,” depending on the context. “Woman” in English used alone without an article captures woman as an institution, a concept, femininity as determined and defined by society, culture, history. Thus in a French sentence such as Le problème de la femme a toujours été un problème d’hommes, we have used “woman” without an article: “The problem of woman has always been a problem of men.”

Beauvoir occasionally — but rarely — uses femme without an article to signify woman as determined by society as just described. In such cases, of course, we do the same. The famous sentence, On ne naît pas femme: on le devient, reads, in our translation: “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman.” The original translation [1989] by H. M. Parshley read, “One is not born, but rather becomes a woman.”

What significance, if any, might this divergence in translations mean if viewed critically through a feminist/gender lens?

The Second Sex: Phallus-Plowshare and Woman-Furrow

In the 1989 translation:

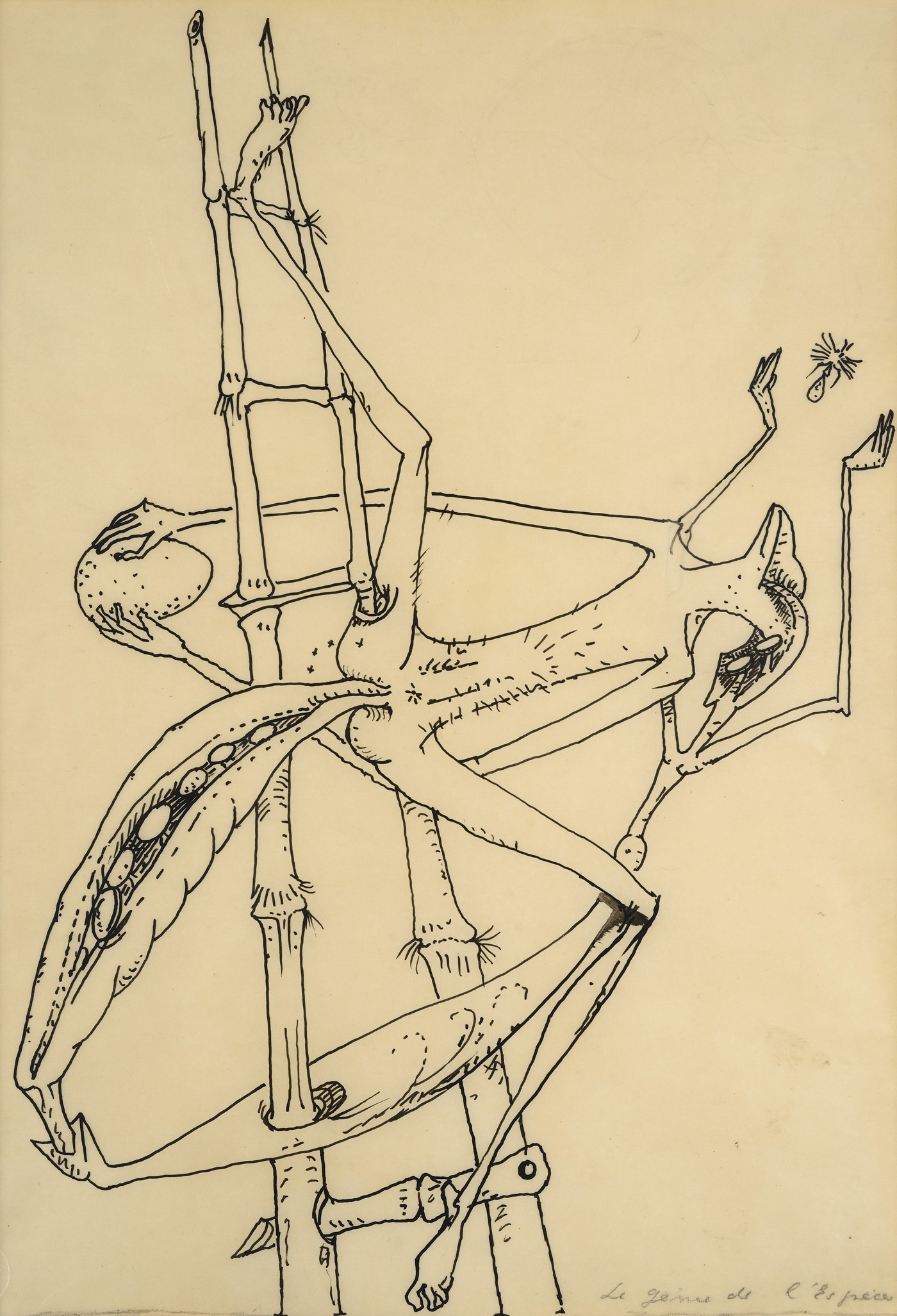

He wishes to conquer, to take, to possess; to have woman is to conquer her; he penetrates into her as the plowshare into the furrow; he makes her his even as he makes his the land he works; he labors, he plants, he sows: these images are old as writing; from antiquity to our own day a thousand examples could be cited: “Woman is like the field, and man is like the seed,” says the law of Manu. In a drawing by Andre Masson there is a man with spade in hand, spading the garden of a woman’s vulva.8 Woman is her husband’s prey, his possession.

8. Rabelais calls the male sex organ “nature’s plowman.” We have noted the religious and historical origin of the associations: phallus-plowshare and woman-furrow. (1989)

The passage to which the #8 footnote refers:

Formerly, he was possessed by the mana, by the land; now he has a soul, owns certain lands; freed from Woman, he now demands for himself a woman and a posterity. He wants the work of the family, which he uses to improve his fields to be…. (1989, 78)

In the 2009 translation:

He wants to conquer, take, and possess; to have a woman is to conquer her; he penetrates her as the plowshare in the furrows; he makes her his as he makes his the earth he is working: he plows, he plants, he sows: these images are as old as writing; from antiquity to today a thousand examples can be mentioned. “Woman is like the field and man like the seeds,” say the Laws of Manu. In an André Masson drawing there is a man, shovel in hand, tilling the garden of a feminine sex. 12 Woman is her husband’s prey, his property.

12. Rabelais called the male sex “the worker of nature.” The religious and historical origin of the phallus-plowshare — woman-furrow association has already been pointed out. (2009, 170-171)

The passage to which the #12 footnote refers:

Formerly he was possessed by the mana, by the earth: now he has a soul, property; freed from Woman, he now lays claim to a woman and a posterity of his own. He wants the family labor he uses for the benefit of his fields to be totally his, and for this to happen, the workers must belong to him: he subjugates his wife and his children. He must have heirs who will extend his life on earth because he bequeaths them his possessions, and who will give him in turn, beyond the tomb, the necessary honors for the repose of his soul. The cult of the domestic gods is superimposed on the constitution of private property, and the function of heirs is both economic and mystical. Thus, the day agriculture ceases to be an essentially magic operation and becomes creative labor, man finds himself to be a generative force; he lays claim to his children and his crops at the same time. (2009, 86-87)

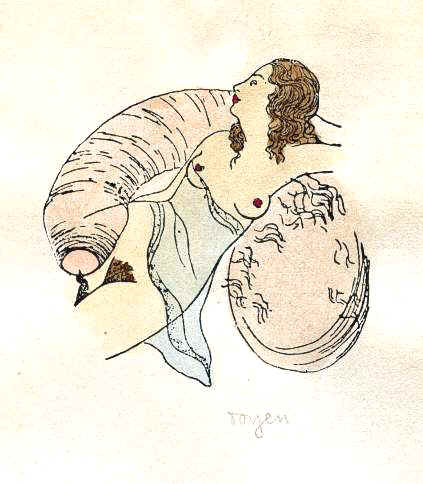

Andre Masson and Toyen

In the Second Sex, Beauvoir

Woman as Siren: Oh Brother Where Art Thou?

Detailed and Alternatively Stylized Scene with Multi-Sensory Focus

In Oh Brother, Where Art Thou? the Odyssey turns Appalachian. In this scene, we have concrete details: women washing clothes and singing their enticing lullaby, the men dirty, sweaty, travel worn, a stream, rocks… In this alternate telling, the sirens physically interact with the men. The sirens are beautiful, their song sweet.

Aside from the auditory representations, both the second and the third film adaptations of “Odysseus and the Sirens” are faithful representations of the first stick figure summary. The stick figure summary, though successful in allowing the viewer to focus on the auditory, leaves a great deal of detail out if one is writing a literary scene, though, the stick figures would be perfect for a light summary rendition on YouTube, and the simplicity can be enjoyable.

It is the writer’s job to balance sensory detail and summary within the narrative. Both are necessary in creating a well-developed narrative, and the summary sections can be effective ligaments for the bones of the narrative, the more detailed and immersive scene work. But consider which of the above adaptations stay with you longer? Which of them transports you more thoroughly?

Redneck Feminism in Good Ol’ Boy Land: Phallus-Plowshare and Woman-Furrow in Popular Culture

This section will become its own lesson, but for some reason, came to me while reading The Second Sex, again. Ahem.

Put your boots on and get ready to dance. As “Boys ‘Round Here” opens, we see a long, green convertible round the street corner and making its way toward the camera. Shelton sings “Red red red red red red redneck…” as the long convertible pumps up and down, plowing the asphalt. Then Shelton makes his way to the same corner, but coming the other way, driving his big red truck. On the bumper is a phrase: “Well with others.” He parks and begins pumping and plowing the asphalt, mirroring the long convertible’s motions. Shelton and the men in the convertible — speculated to be rappers but are actually actors playing the part in the video — exchange admirations for each others’ pumping and plowing of the asphalt. They are all smiling wide at their vehicles pumping and plowing the asphalt street.

Cut to Blake Shelton reclining in a chair on his porch, boots kicked up and leaning on the porch rail. Pistol Annies stand to the side, one of them, Miranda Lake, his wife. Consider their position to Blake Shelton as he reclines on his chair, drinking his beer on the porch.

Later, during their focal scenes, they are positioned and costumed with a great deal of care. As with all great film, and yes, music videos, positioning and costuming of “characters” means a great deal in the subtext of the scene or sequence. What does the positioning and costuming of Pistol Annies represent for you as the viewer? Furthermore, in the below lyrics, you’ll find Pistol Annies’ backup lyrics. What response is conjured in you, as the viewer and listener?

Also, how might Marxist and critical race theories play significantly within the contexts of this video?

“Boys ‘Round Here” Lyrics

Songwriters: Craig Wiseman, Dallas Davidson, Rhett Akins

Run ole Bocephus through a jukebox needle

At a honky-tonk, where their boots stomp

All night what? (That’s right)

Gotta get it in the ground ‘fore the rain come down

To get paid, to get the girl

In your 4 wheel drive (A country boy can survive)

Drinking that ice cold beer

Talkin’ ’bout girls, talkin’ ’bout trucks

Runnin’ them red dirt roads out, kicking up dust

The boys ’round here

Sending up a prayer to the man upstairs

Backwoods legit, don’t take no shit

Chew tobacco, chew tobacco, chew tobacco, spit

Red red red red red red red red red red redneck

Ain’t a damn one know how to do the dougie

(You don’t do the dougie?) No, not in Kentucky

But these girls ’round here yep, they still love me

Yeah, the girls ’round here, they all deserve a whistle

Shakin’ that sugar, sweet as Dixie crystal

They like that y’all and southern drawl

And just can’t help it cause they just keep fallin’

Drinking that ice cold beer

Talkin’ ’bout girls, talkin’ ’bout trucks

Runnin’ them red dirt roads out, kicking up dust

The boys ’round here

Sending up a prayer to the man upstairs

Backwoods legit, don’t take no shit

Chew tobacco, chew tobacco, chew tobacco, spit

(Ooh let’s ride)

Through the country side

(Ooh let’s ride)

Down to the river side

Me and you gonna take a little ride to the river

Let’s ride (That’s right)

Lay a blanket on the ground

Kissing and the crickets is the only sound

We out of town

Have you ever got down with a

Red red red red red red red red red red redneck?

Do you wanna get down with a,

Red red red red red red red red red red redneck?

Girl you gotta get down

Drinking that ice cold beer

Talkin’ ’bout girls, talkin’ ’bout trucks

Runnin’ them red dirt roads out, kicking up dust

The boys ’round here

Sending up a prayer to the man upstairs

Backwoods legit, don’t take no shit

Chew tobacco, chew tobacco, chew tobacco, spit

(Ooh let’s ride)

I’m one of them boys ’round here

(Ooh let’s ride)

Red red red red red red red red redneck

(Ooh let’s ride)

So come on girl, hop inside

Me and you, we’re gonna take a little ride

Lay a blanket on the ground

Kissing and the crickets is the only sound

We out of town

Girl you gotta get down with a

Come on through the country side

Down to the river side

The Dixie Chicks took some heat for the satirical song and video, “Goodbye Earl.” Have they gone too far? How does the satire in this song and video compare to Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal? How do they use chiaroscuro in tone and context to heighten the impact? Does it change your view of the song, at all, to know that it was written by Dennis Linde?

“Goodbye Earl”

Songwriter: Dennis Linde

All through their high school days

Both members of the 4H club, both active in the FFA

After graduation

Mary Anne went out lookin’ for a bright new world

Wanda looked all around this town and all she found was Earl

Wanda started gettin’ abused

She’d put on dark glasses or long sleeved blouses

Or make-up to cover a bruise

Well she finally got the nerve to file for divorce

And she let the law take it from there

But Earl walked right through that restraining order

And put her in intensive care

On a red eye midnight flight

She held Wanda’s hand as they worked out a plan

And it didn’t take ’em long to decide

Those black-eyed peas, they tasted alright to me, Earl

You’re feelin’ weak? Why don’t you lay down and sleep, Earl

Ain’t it dark wrapped up in that tarp, Earl

They searched the house high and low

Then they tipped their hats and said, thank you ladies

If you hear from him let us know

Well, the weeks went by and spring turned to summer

And summer faded into fall

And it turns out he was a missing person who nobody missed at all

Out on highway 109

They sell Tennessee ham and strawberry jam

And they don’t lose any sleep at night, ’cause

We need a break, let’s go out to the lake, Earl

We’ll pack a lunch, and stuff you in the trunk, Earl

Is that alright? Good! Let’s go for a ride, Earl, hey!

Ooh hey hey hey, ummm hey hey hey, hey hey hey

“Speak to a Girl”

She don’t really care how you’re spending your money, it’s all how you treat her

She just want a friend to be there when she opens her eyes in the morning

She wants you to say what you mean and mean everything that you’re saying

That’s how you get with the lady who’s worth more than anything in your whole world

You better respect your Mama, respect the hell out of her

‘Cause that’s how you talk to a woman and that’s how you speak to a girl

She just wanna feel that you’re real, that she’s near to the man that’s inside

She don’t need to hear she’s a queen on a throne, that she’s more than amazing

She just wants you to say what you mean and to mean everything that you’re saying

That’s how you get with a lady who’s worth more than anything in your whole world

You better respect your mama, respect the hell out of her

‘Cause that’s how you talk to a woman, that’s how you speak to a girl

That’s how you speak to, speak to her

That’s how you get with a lady who’s worth more than anything in your whole world

You better respect your mama, respect the hell out of her

‘Cause that’s how you talk to a woman and that’s how you speak to a girl

That’s how you talk to a woman, that’s how you speak to a girl

Plows and mules in Their Eyes Were Watching God

“Naw, Ah needs two mules dis yeah. Taters is goin’ tuh be taters in de fall. Bringin’ big prices. Ah aims tuh run two plows, and dis man Ah’m talkin’ ’bout is got uh mule all gentled up so even uh woman kin handle ’im.”

Logan held his wad of tobacco real still in his jaw like a thermometer of his feelings while he studied Janie’s face and waited for her to say something. (Huston 766)

“Come to yo’ Grandma, honey. Set in her lap lak yo’ use tuh. Yo’ Nanny wouldn’t harm a hair uh yo’ head. She don’t want nobody else to do it neither if she kin help it. Honey, de white man is de ruler of everything as fur as Ah been able tuh find out. Maybe it’s some place way off in de ocean where de black man is in power, but we don’t know nothin’ but what we see. So de white man throw down de load and tell de nigger man tuh pick it up. He pick it up because he have to, but he don’t tote it. He hand it to his womenfolks. De nigger woman is de mule uh de world so fur as Ah can see. Ah been prayin’ fuh it tuh be different wid you. Lawd, Lawd, Lawd!” (Hurston, 556-557)

“You behind a plow! You ain’t got no mo’ business wid uh plow than uh hog is got wid uh holiday! You ain’t got no business cuttin’ up no seed p’taters neither. A pretty doll-baby lak you is made to sit on de front porch and rock and fan yo’self and eat p’taters dat other folks plant just special for you.” (Hurston, 809)

Works Cited

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. Translated by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier, Vintage Books, 2009.

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. Translated by H. M. Parshley, Vintage Books, 1989.

Blake Shelton. “Boys ‘Round Here.” Based on a True Story…, Ten Point Productions, Inc., 2013, YouTube, youtube.com/embed/JXAgv665J14.

Dixie Chicks. “Goodbye Earl.” Fly, Sony Music Entertainment Inc., 1999. YouTube, youtube.com/embed/Gw7gNf_9njs.

Gilman, Richard. “The Man Behind the Feminist Bible.” The New York Times, 22 May 1988, nytimes.com/1988/05/22/books/the-man-behind-the-feminist-bible.html. Accessed 4 Sept. 2017.

Masson, André. Le génie de l’espèce (The Genius of the Species). 1942, drypoint and engraving, The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Menand, Louis. “Stand by Your Man: The Strange Liaison Between Sartre and Beauvoir.” The New Yorker, 26 Sept. 2005, newyorker.com/magazine/2005/09/26/stand-by-your-man. Accessed 2 Sept. 2017.

“Simone de Beauvoir: Journalist, Women’s Rights Activist, Academic, Activist, Philosopher (1908–1986).” Biography, 28 Apr. 2017, biography.com/people/simone-de-beauvoir-9269063. Accessed 2 Sept. 2017.

Toyen. Dívčí sen II (A Girl Dream II). 1932. zincography and aquarelle, The ART Gallery, Chrudim.

One is not born, but rather becomes, woman.” —Simone de Beauvoir

One is not born, but rather becomes, woman.” —Simone de Beauvoir