Writing about loneliness and isolation, in House of Coates, author Brad Zellar makes intriguing and vital observations on types of character traits that defy cultural assumptions and stereotypes of masculinity. Combining vivid writing with photographs by Alec Soth, the novel becomes an enlivened testament to our complicated associations and relationships with the world and each other. Here, Zellar speaks more to these themes, as well as discusses different innovative writing craft techniques.

Chelsey Clammer: There is the stereotype in American society that men must be tough, ruthless, unconquerable, even. House of Coates, in a way, looks at what happens when these expectations are challenged and broken. I’m curious about how you think loneliness and the sense of being broken impact the social constructions of masculine gender roles. What do you think are some of the consequences of these gender stereotypes when they are instilled, but also subverted?

Brad Zellar: I wonder a lot about gender and coping strategies for things like loneliness and disappointment. It seems to me that most of the women I know handle isolation in a more constructive way, but I could be wrong about that. I do know, though, that there’s this ingrained thing with a lot of guys where they feel the need to run and hide, and to try to reinvent themselves as self-sufficient. It’s the action-male instinct, I think, the thing that drives survivalists and all sorts of men who maybe watched too many westerns or ingested a bit too much Thoreau or Kerouac when they were younger. Active isolation. Be a moving target, even if no one’s really gunning for you.

There’s no question that the masculine stereotype of the stoic—the cowboy, the mountain man, etc.—exacerbates loneliness, depression, economic struggles, and all manner of other hardships. And I don’t think American society and culture does a very good job anymore of preparing anyone for those stereotypical masculine roles (probably to its credit) and the result is that a lot of these lonely drifters are just soft, bad actors who don’t have a clue or an audience. Lester B. Morrison is a guy who is crippled by a very common strain of romantic and toxic mythology.

CC: The beginning of the book weaves setting and character together—the two bounce off of one another, then slowly merge and form a very stark and vulnerable story about Lester B. Morrison. What role do you see setting/place having in this story? Other than location, what purpose do you think it serves?

BZ: The setting was a very deliberate choice. And it’s a real place, more or less. I’ve always been attracted to John Ruskin’s idea of the pathetic fallacy, and if misery truly loves company than I think it stands to reason that somebody who feels desolate and fouled will seek out a landscape or an environment that mirrors what they’re feeling. It’s obviously not healthy, but I can attest from personal experience that it happens. The area around that refinery south of the Twin Cities—particularly in the dead of winter—is about as inhospitable a place as you can imagine. I’d spent a good deal of time poking around there, and when I was writing House of Coates it just seemed like the natural place to do it. I had no plans initially to set the story there; I was just looking for a suitable spot to hole up and work without distraction. But once I was hunkered down in a little strip motel up the highway from the refinery—and this was in the middle of a particularly dreadful Minnesota winter—the environment became a major distraction and a central part of the experience, and I started seeing Lesters everywhere.

BZ: The setting was a very deliberate choice. And it’s a real place, more or less. I’ve always been attracted to John Ruskin’s idea of the pathetic fallacy, and if misery truly loves company than I think it stands to reason that somebody who feels desolate and fouled will seek out a landscape or an environment that mirrors what they’re feeling. It’s obviously not healthy, but I can attest from personal experience that it happens. The area around that refinery south of the Twin Cities—particularly in the dead of winter—is about as inhospitable a place as you can imagine. I’d spent a good deal of time poking around there, and when I was writing House of Coates it just seemed like the natural place to do it. I had no plans initially to set the story there; I was just looking for a suitable spot to hole up and work without distraction. But once I was hunkered down in a little strip motel up the highway from the refinery—and this was in the middle of a particularly dreadful Minnesota winter—the environment became a major distraction and a central part of the experience, and I started seeing Lesters everywhere.

CC: While the writing and content create that beautifully stark tone I spoke of earlier, I feel like the photographs are not just a part of the narrative, but a part of the actual writing of House of Coates, as well. How do you see the photographs interacting with the text? What parts, themes, and/or topics do you think come alive because of the mixed media?

BZ: The original drafts of the book were much, much longer, and there was much more in the way of description. The beauty of working with photographs—and Alec Soth (who took the pictures with a disposable camera) and I have worked together on a number of projects—is that you always know you have a lot of freedom to pare things way down. The pictures carry so much of the weight, and let you off the hook in terms of having to unpack everything. In this instance, they could not only show the place, but also reflect Lester’s point of view. And not only what he was seeing but how he was seeing it and how it was affecting him. So much of the book’s mood and atmosphere are established by those woozy, off-focus photos. When I’m working with photos my models are always the picture books that I read as a child; the great ones are such models of economy and collaboration, and I find that when I remember them I’m no longer sure which parts of my memories are related specifically to the words, and which to the pictures. You’re always shooting for that sort of a marriage.

CC: In Adrienne Rich’s poem “Song,” she writes:

You want to ask, am I lonely?

Well, of course, lonely

as a woman driving across country

day after day, leaving behind

mile after mile

little towns she might have stopped

and lived and died in.

Do you think there is any sense of freedom that can be found within loneliness? Or is it a trap from which we can never fully escape? And finally, as spirituality becomes a theme later on in the novel, how do you think spirituality fits in with this?

BZ: This is where it’s easy to get hung up. I think so many of the more romantic notions of “freedom” are fraught with loneliness once you actually try to make your break. The whole question is also, of course, much more complicated at a time when there are so many ersatz virtual communities in cyberspace. The bottom line is that I believe that most people, no matter how introverted or solitary, really crave some sort of connection and some sort of engagement. Real world connection and engagement. And a lot of that requires an assertiveness that many lonely people don’t have. Spirituality—or an even more old-fashioned term, faith—is a form of connection that can either lead people back into the world, or even farther away from it, and I’m not trying to disparage it by saying that it often worms its way into people’s lives when they’re most vulnerable or in need. Of something. Some sense that they’re not invisible and that their do have meaning or purpose. I’m all for it if it fills the hole, just as long as people don’t use it as a hammer or a wedge.

CC: I want to provide some examples of how the language, pace and structure of each sentence in the novel is, well, astounding.

CC: I want to provide some examples of how the language, pace and structure of each sentence in the novel is, well, astounding.

“Have you ever had the feeling that there wasn’t a soul left on the planet that remembered your name or face or the sound of your laugh? That was a Lester question, and his answer was yes.”

“The poisons were making their way through two or three feet of snow and creating swirling scarves of steam in the freezing air.”

“It’s not about light. It’s about finding a way to live in the darkness.”

There isn’t a question here—I just wanted to point out the lyricism and power of the actual writing in House of Coates, and also to thank you for bringing such beautiful sentences into the world.

CC: What are you working on?

BZ: I’m always writing fiction, but I do it mainly because it’s what I enjoy, and I have never really done anything with it, or at least not for more than 20 years. For the last several years Alec and I have been traveling all over the country and working on a project called The LBM Dispatch. It’s a shifty—and sort of shape-shifting—combination of documentary work, travelogue, and basic storytelling using words and pictures. We’ve pretty much wrapped up our travels (and have published seven newspaper installments of the work) and are in the process of putting together a book about the experience. I’m also finally trying to pull together some of my fiction to toss out into the world. It’s a giant archaeological project.

CC: Is there anything else you would like readers to know?

BZ: Try to be nice to each other. There are a lot of people out there who feel insignificant and invisible. It doesn’t take much to make a small difference in their lives.

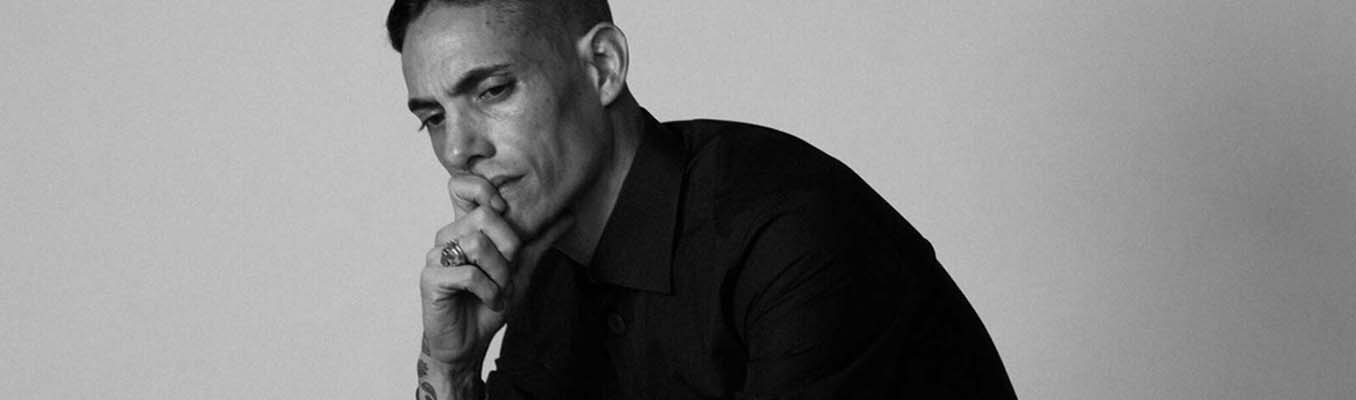

Brad Zellar has written and published fiction, and worked as a writer and editor for daily and weekly newspapers, as well as for both regional and national magazines. A former senior editor at City Pages, The Rake, and Utne Reader, Zellar is also the author of Suburban World: The Norling Photos, Conductors of the Moving World, and House of Coates. For the last three years he has been collaborating with the photographer Alec Soth on “The LBM Dispatch,” an irregularly published newspaper that chronicles American community life in the 21st century. Soth and Zellar are presently at work on a book documenting the experience.

Chelsey Clammer has been published in The Rumpus, Essay Daily, and The Nervous Breakdown among many others. She is the Managing Editor and Nonfiction Editor for The Doctor T.J. Eckleburg Review, as well as a columnist and workshop instructor for the journal. Clammer is also the Nonfiction Editor for Pithead Chapel and Associate Essays Editor for The Nervous Breakdown. She has two essay collections forthcoming in Spring 2015. www.chelseyclammer.com.

Working with a community organization in Minneapolis, artist Christi Furnas not only helps other artists with mental illnesses to improve their art-making skills, but does so in a safe space that is free of stigma. As someone who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, Furnas uses her history of mental illness in order to inform how to help others who are going through similar experiences. Here, Furnas discusses the intersection of the role art and the creation of beauty play towards a deeper level of communication.

Working with a community organization in Minneapolis, artist Christi Furnas not only helps other artists with mental illnesses to improve their art-making skills, but does so in a safe space that is free of stigma. As someone who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, Furnas uses her history of mental illness in order to inform how to help others who are going through similar experiences. Here, Furnas discusses the intersection of the role art and the creation of beauty play towards a deeper level of communication. I have a unique roll because I get to support peeps as an equal. I don’t see it happen where I work, but in a great number of situations people with mental illness are patronized or not listened to. It’s difficult to value yourself when no one else seems to value who you are or what you say. I have the opportunity through art making to connect with people. It is important to hear stories from people and be able to share experiences. The other day I compared auditory hallucination stories with an artist in the program. Then I discussed which colors to use in their painting. I feel extremely fortunate to work in the arts at a place I can be open about my illness.

I have a unique roll because I get to support peeps as an equal. I don’t see it happen where I work, but in a great number of situations people with mental illness are patronized or not listened to. It’s difficult to value yourself when no one else seems to value who you are or what you say. I have the opportunity through art making to connect with people. It is important to hear stories from people and be able to share experiences. The other day I compared auditory hallucination stories with an artist in the program. Then I discussed which colors to use in their painting. I feel extremely fortunate to work in the arts at a place I can be open about my illness. CF: Stigma is everywhere. I believe it is starting to get better slowly. On the one hand, we have bad movies and endless news reports blaming violence on the mentally ill. On the other hand, there are organizations like The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and countless people working to advocate for us. More people seem to be speaking out about their own experiences.

CF: Stigma is everywhere. I believe it is starting to get better slowly. On the one hand, we have bad movies and endless news reports blaming violence on the mentally ill. On the other hand, there are organizations like The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and countless people working to advocate for us. More people seem to be speaking out about their own experiences.

At the place I am now, I do not deny my illness, but I do not identify myself by it either. My identity is complex and simple and nonexistent at the same time. Other Buddhists might understand what I’m trying to say. I’m not going to get into an existential conversation right now. What I am going to say is that I try to present the person that I aspire to be to people while trying to be honest about who I am to myself. At times, these two things merge. That is beauty. People recognize beauty, and it’s hard to hate and fear beauty.

At the place I am now, I do not deny my illness, but I do not identify myself by it either. My identity is complex and simple and nonexistent at the same time. Other Buddhists might understand what I’m trying to say. I’m not going to get into an existential conversation right now. What I am going to say is that I try to present the person that I aspire to be to people while trying to be honest about who I am to myself. At times, these two things merge. That is beauty. People recognize beauty, and it’s hard to hate and fear beauty.