Words are everywhere for me lately. That may sound like a big “no, duh ” since I’m a writer, but I’ve been thinking a lot about words lately. Really thinking about them. And not just in that way you do when a really common word suddenly sounds odd to you, like when the word “when” suddenly sounds like it shouldn’t mean anything, like it’s just a sound – when, when, when. Which is what it is after all, but you know what I mean. Or what it means. Or maybe you don’t.

Maybe it’s because the annual Associated Writing Programs conference is just a tad over month away. A couple years ago, when the annual AWP conference was in DC, I heard Luca DiPierro speak on a panel about teaching comics and graphic novels. He said some words, a paraphrase of French writer, Michel Butor, along the lines of “Words are something we look at. Images are also something we read.” So taken was I by this idea that I integrated it into a unit on the role of writing in visual art for an art history through theme course I teach. It wasn’t the looking at words part that struck me. I already taught a whole unit on the idea that words are something we look at in art. It was the images are something we read part. I stress to my students that this doesn’t just mean we look for meaning in images. It goes a bit deeper for DiPierro and a bit freakier for me. It has to do with how DiPierro literally cuts each of his images out of painted paper, cuts them out as individual items without meaning in themselves, and then combines and recombines these items–as a writer does with words–until the meaning is created for him. Blew my mind. Okay, so not so hard to do that. But it’s a rare art “concept” that sticks with me, that’s durable, especially with all the fuzzy, self-indulgent artist statements out there.

So, fast forward to this holiday season – I’m in the BMA gift shop, gathering ideas for a museum store shopping guide article I had in mind (never materialized), and I pick up Austin Kleon’s Steal Like an Artist. A book full of brilliant, if known, morsels of wisdom on how to go about being creative. Love it. Buy it. End up buying it several more times for several friends who are writers. And I look into this Austin Kleon guy, who turns out to be a poet and artist, whose main schtick is those cross-0ut-words-from-newsprint poems. Clever, might try it one day. And then I start to think about whether or not it’s fair to be so dismissive of this form, and I start thinking about it more. About how my vocabulary in the English language is a limited set. About how any writer already works with a limited set of words. About how we choose from that set further limited on any given day by what we dreamed the night before, what we heard on NPR on the way to work, what we experienced in the coffee shop wait line. And about how a sheet of newspaper on any given day is just another limited set of words to draw from.

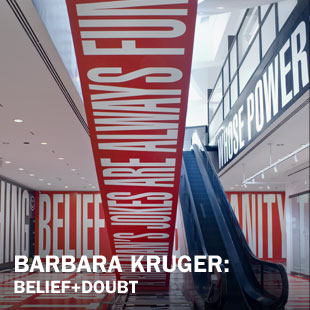

At the very same time, back in DC again, the Hirshhorn is plastered with words, the whole bottom level, top, sides of it, floor. Barbara Kruger has swathed–avec crew of many men–the entire surface area with a series of words. Imperatives, questions, and pithy flat-out statements confront you in red, white, and black, several feet high. Any of them startling? Not really. Kruger, in this show she has called Belief + Doubt, pulls them from our common experience, chooses words for us from the swirling storm that surrounds us daily. Lays them out for us. Literally. Lays them out to be walked on and read. To force us to crane our necks, stand back, view from above. To see these words and to read. And read into them. To think. About words.

I leave you with these thoughts. These words. Think about them. Play with them. Recombine them. Cross them out and make a poem from the remnants. I think I might just go and do the same.

Heidi Vornbrock Roosa is a grad of the Johns Hopkins MA in Writing program. Her fiction is available in The South Dakota Review, The Summerset Review, and in Shots (as Regina Harvey).

The Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture houses a broad collection of photographs, hand-woven patchwork quilts, military artifacts, paintings, and local children’s artwork. On the third floor is an installation with a video component honoring the more than thirty documented cases of lynchings that occurred in Maryland between 1870 and 1933. This installation is contained in a small circular room that invites the viewers to immerse themselves in an experience of hostility, brutality, and senseless violence. Created in 2005 by Oletha DeVane, Witness is an installation that stands apart from the rest of the museum.

The Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture houses a broad collection of photographs, hand-woven patchwork quilts, military artifacts, paintings, and local children’s artwork. On the third floor is an installation with a video component honoring the more than thirty documented cases of lynchings that occurred in Maryland between 1870 and 1933. This installation is contained in a small circular room that invites the viewers to immerse themselves in an experience of hostility, brutality, and senseless violence. Created in 2005 by Oletha DeVane, Witness is an installation that stands apart from the rest of the museum. s to preview the installation before deciding if children should be permitted to view it, making it clear that the experience will be unsettling and raw. The floor has been made to look like hard, dry dirt littered with rocks — a bumpy, uneven surface unsteady beneath the feet. To the right is a wall covered in large, distorted mirrors, similar to those found in funhouses. The mirrors alter, widen, and shorten the viewer, provoking the feel of an uncomfortable silence during a serious and personal conversation. To the left a flat screen hangs from the wall. On it are projected images of faces of the known lynch victims. Expert voices describe life in Maryland during this era. The video shifts to a view of tree branches reflected over a rippling mass of water, and the solemn voices list names of the more than 30 people lynched in Maryland and the counties in which they died. Above are the branches. Most are made of cloth and felt, with fake cloth leaves dangling from their limbs. One is a stem wrapped entirely in rope, but a few stems are covered wholly in reflective pieces of glass. The branches hang overhead, omnipresent and looming, and the viewer stands surrounded in darkness, branches overhead, on unsteady ground, watching the reflection of branches over rippling water, and listening to the names attached to familiar places — places that they’ve been, places that they may even live, and then it will hit them — the understanding that Ms. DeVane herself stated was the goal of her whole project.

s to preview the installation before deciding if children should be permitted to view it, making it clear that the experience will be unsettling and raw. The floor has been made to look like hard, dry dirt littered with rocks — a bumpy, uneven surface unsteady beneath the feet. To the right is a wall covered in large, distorted mirrors, similar to those found in funhouses. The mirrors alter, widen, and shorten the viewer, provoking the feel of an uncomfortable silence during a serious and personal conversation. To the left a flat screen hangs from the wall. On it are projected images of faces of the known lynch victims. Expert voices describe life in Maryland during this era. The video shifts to a view of tree branches reflected over a rippling mass of water, and the solemn voices list names of the more than 30 people lynched in Maryland and the counties in which they died. Above are the branches. Most are made of cloth and felt, with fake cloth leaves dangling from their limbs. One is a stem wrapped entirely in rope, but a few stems are covered wholly in reflective pieces of glass. The branches hang overhead, omnipresent and looming, and the viewer stands surrounded in darkness, branches overhead, on unsteady ground, watching the reflection of branches over rippling water, and listening to the names attached to familiar places — places that they’ve been, places that they may even live, and then it will hit them — the understanding that Ms. DeVane herself stated was the goal of her whole project.