Described as brilliantly gorgeous and a much-needed offering, Amber Dawn brings a poetic voice to her socially-aware writing. Traversing issues such as sex work and queer sexuality, feminism and class, as well as identity and literature, Dawn brings attention to pressing social concerns in an accessible and literary way. Here, Dawn discusses writing as a way of healing, her approach to and relationship with different art forms, and crafting writing in a way that creates an immersive experience for the reader.

Described as brilliantly gorgeous and a much-needed offering, Amber Dawn brings a poetic voice to her socially-aware writing. Traversing issues such as sex work and queer sexuality, feminism and class, as well as identity and literature, Dawn brings attention to pressing social concerns in an accessible and literary way. Here, Dawn discusses writing as a way of healing, her approach to and relationship with different art forms, and crafting writing in a way that creates an immersive experience for the reader.

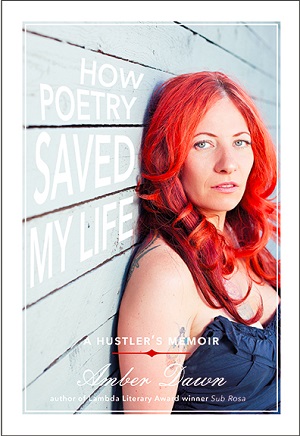

Chelsey Clammer: Last year, Arsenal Pulp Press published your memoir How Poetry Saved My Life. In this past year your “hustler’s memoir” was a finalist for the 26th Annual Lambda Literary Awards and also won the 2013 City of Vancouver Book Award. What has been your response to seeing how a book that is not just about the controversial and complicated topics of sex work, surviving trauma, activism and queer sexuality, but is also largely about the importance of poetry and literature in our lives, being so well-received by a multitude of readers?

Amber Dawn: We are more complex than marketing trends and popular culture allow us to be. As a writer and a truth-teller, I got discouraged along the way. I received professional feedback that my whole story was too complicated, too overwhelming, too outsider, too uneven, too true, etc. For example, why couldn’t I just tell a sex worker story and leave out the “queer stuff”—the “queer stuff” would limit my marketability. Then I found the right publisher; Arsenal Pulp Press is interested in dynamic, manifold stories. I found creative writing techniques that helped me invite my readers in—like direct address, second person point-of-view, avoidingvoyeuristic narration, mixing verse and prose, asking questions, and outrightly asking for the readers’ allyship. The recognition I’ve received reminds me that—yes—we are all complex and we yearn to have our complexities made visible.

CC: Your first book, Sub Rosa, was a novel about magical prostitutes who fend off bad johns. Aside from this novel and your memoir, which includes your poetry, you have also written erotica and short stories, and you are also a filmmaker. Does your approach to these genres and art forms differ? Do they ever influence or challenge one another?

AD: I never know how to answer this question. It’s like asking me how I juggle sleeping and waking life. It’s all life. I actually find it odd that any artist would want to focus on a single form or discipline. I love (and feel nervous about) trying out new creative practices. Recently, at the Vancouver Verses Festival I tried my hand at stand-up comedy with audience participation. What a unique and exhilarating challenge. I also love abandoning the idea that literary fiction is the ultimate genre in creative writing, when there are so many ways to express ourselves. I encourage all artists to get out of their genre comfort zone and work in another form or discipline. Try it! I promise you will discover something about yourself and your creative work if you do.

CC:For me, the ways in which you brought your poetry into your life’s stories and allowed the two genres to speak to one another in How Poetry Saved My Life completely shifted the way I considered self-expression through writing. Your memoir showed me how one event can bring on multiple meanings when looked at through different kinds of writing. Do you feel as if there are some stories or moments in your life that can be expressed better through one genre than another?

CC:For me, the ways in which you brought your poetry into your life’s stories and allowed the two genres to speak to one another in How Poetry Saved My Life completely shifted the way I considered self-expression through writing. Your memoir showed me how one event can bring on multiple meanings when looked at through different kinds of writing. Do you feel as if there are some stories or moments in your life that can be expressed better through one genre than another?

AD: To me the highest form of writing or storytelling is when the genre and the content work together to create an immersive experience for the reader—an experience that invites the reader to explore meaning and message more fully. TS Eliot said that, “Poetry can communicate before it is understood.” I have returned to this quote again and again, just as I have returned to the much more recent quote by Jeanette Winterson, “A tough life needs a tough language—and that is what poetry is.” Wisdoms such as these gave me the permission I needed to include stray from a traditional chronology of narrative events and use poetry in my memoir. Poetry is a language that most of us don’t naturally speak, and so I used poetry to write about experiences of sex work and survivorship that many of us don’t comfortably or authentically articulate.

CC: In your memoir, you explain how you joined an anti-violence, feminist collective in 1995. From this experience you state, “I learned immediately that the phrase ‘as a sex worker’ is not met with the same gravity as other women’ qualifiers” (51). In the past decade, have you seen a change in feminists’ reactions to a woman identifying herself as a sex worker?

AD: I see change and push back, change and push back. As if the feminist sex wars (and all debates about sex work) are stuck on some giant, relentless pendulum. We’ve seen many victories and many more set backs, so much hope and still pervasive stigma, we watch our sisters and brothers beat down and killed while we lobby for real changes—changes that in essence seems so darn simple from my perspective. My peers and friends who have remained very central to sex work activism are nothing short of heroes. I can’t be that kind of front-line hero. These days, I like to imagine myself as holding up my activist peers from behind. I write stories and I speak my truth, and I have faith my humble contributions have value within a very critical movement of sex work activism.

CC:There are a good number of books, individuals, and organizations who explore and teach how writing can be a form of healing for trauma survivors. What has been your experience with this?

AD: I am so grateful to be part of a movement that fosters the connection between healing and creative practice. Many of my nearest and dearest sought art as a way to be visible—and developed their creative practices as a means to heal themselves and their communities. I was barely twenty years old when I met author/musician Nomy Lamm. Nomy’s zine I‘m So Fucking Beautiful was filled with powerful anecdotes on being a “bad ass, fat ass, Jew, dyke, amputee.” In the 90s, I lived in the same house with community-based researcher Dr. Sarah Hunt, who has dedicated years of work to strengthening relationships between Indigenous sex workers and other members of Indigenous communities. In 2004, I met author/activist Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, who’s creative writing workshop description goes like this, “Queer, trans, gender non conforming and Two Spirit Black, Indigenous and People of Color who are disabled, chronically ill, Deaf, neurodiverse and/or Crazy: what stories do our bodies and lives have to tell…” I could list my peers and mentors—and their contributions—endlessly. The three I’ve mentioned here, however, have websites, YouTube videos, free online writing samples, books for sale, workshops and appearances, etc. Look them up.

CC:Let’s talk for a second about having a room of one’s own. Virginia Woolf has a damn good point that all any woman needs in order to write is some money to live off of and a room in which she can seclude herself. When I read Woolf’s book in undergrad, I liked what she had to say, but thought to myself, Well, damn it. I’m a broke college student and share a dorm room with three other women. What the hell am I supposed to do? Soon after asking this question, I read “Speaking in Tongues” by Gloria Anzaldúa and got my answer. Anzaldúa says: “Forget the room of one’s own–write in the kitchen, lock yourself up in the bathroom. Write on the bus or the welfare line, on the job or during meals, between sleeping and waking.” Throughout the different financial and living situations you have been in throughout your life, where and how has writing been a part of those? And what are your thoughts on the intersection of class, gender and creative work?

CC:Let’s talk for a second about having a room of one’s own. Virginia Woolf has a damn good point that all any woman needs in order to write is some money to live off of and a room in which she can seclude herself. When I read Woolf’s book in undergrad, I liked what she had to say, but thought to myself, Well, damn it. I’m a broke college student and share a dorm room with three other women. What the hell am I supposed to do? Soon after asking this question, I read “Speaking in Tongues” by Gloria Anzaldúa and got my answer. Anzaldúa says: “Forget the room of one’s own–write in the kitchen, lock yourself up in the bathroom. Write on the bus or the welfare line, on the job or during meals, between sleeping and waking.” Throughout the different financial and living situations you have been in throughout your life, where and how has writing been a part of those? And what are your thoughts on the intersection of class, gender and creative work?

AD: I deeply admire Virginia Woolf for advocating for women authors to have a room of one’s own. I deeply admire the scores of women artists who advocate for equal working conditions and recognition, like the Guerilla Girls, for example. For me, however, I’m with Anzaldúa, I want my creative practice to meet me where I’m at–which is not a room of my own. I still do not have a room of my own, and I certainly don’t let that stop me from creating exceptional work. Personally, I don’t expect or desire the type of working conditions or recognition as acclaimed white, male artist in the North America. Part of my commitment to queer and feminist artmaking and storytelling is to allow my creative practice and voice to exist outside of institutional recognition and the “American dream” of artmaking. I’m more so interested in holding street-based art in as high as regard as the gallery exhibition, or respecting the self-published chapbook as much as the publishing house hardcover. I’m keen to celebrate artists and voices that aren’t deemed best-sellers in popular discourse. As I said earlier in this interview, the industry market is reductive—it’s still grossly status quo, white, and driven by the promise of happiness and so-called success. To date, my favourite, most esteemed readings and writing workshops take place in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside/the V6A—one of the lowest-income neighbourhoods in the nation with some of the most interesting artists.

CC:What are you working on now?

AD: I’ve just finished my first poetry collection (entirely poetry, no prose). Where the Word Ends and My Body Begins is a collection of glosa form poems written as an homage to and an interaction with seventeen leaders in queering verse—a mix of celebrated poets like Gertrude Stein, Christina Rossetti and Adrianne Rich and the close peer voices I dearly admire like Leah Horlick and Trish Salah. Garnering muse and momentum from these poets, I guess I attempt to delve deeper into the themes of trauma, memory, relations, and unblushing sexuality. Themes that I’ve been working with throughout my creative practice. Arsenal Pulp Press and I will launch this collection in Spring 2015.

Amber Dawn is a writer from Vancouver, Canada. Author of the memoir How Poetry Saved My Life and the Lambda Award-winning novel Sub Rosa, and editor of the anthologies Fist of the Spider Women: Fear and Queer Desire and With A Rough Tongue. Her first collection of poetry, Where the Word Ends and My Body Begins, is forthcoming in Spring 2015.

Chelsey Clammer received her MA in Women’s Studies from Loyola University Chicago, and is currently enrolled in the Rainier Writing Workshop MFA program. She has been published in The Rumpus, Atticus Review, and The Nervous Breakdown among many others. She has won many awards, most recently the Owl of Minerva Award 2014 from the women’s literary journal Minerva Rising. Clammer is the Managing Editor and Nonfiction Editor for The Doctor T.J. Eckleburg Review, as well as a columnist and workshop instructor for the journal. Her first collection of essays, There is Nothing Else to See Here, is forthcoming from The Lit Pub, Winter 2014. You can read more of her writing at: www.chelseyclammer.com.

Thank you, Chelsey Clammer, for this interview. You’re questions gave me a lot to work with.