Half a block from London Kashmir’s Beverly Hills mansion on North Roxbury Drive, “once the home of Caesar Romero during Hollywood’s golden age” according to my star map, I stop and peer behind me into the nearly total darkness. On my left is an eight-foot high wrought-iron fence that surrounds the property; across the street, a Tudor-style ranch house now owned by an heir to the Revlon fortune. Taking a step, I think I hear it again, a crunching sound. It could be my own echo. It could be the wind. I can’t always trust my senses when I’m this close to the living, breathing presence of London Kashmir.

I proceed until the mansion is in full view: three stories high, mansard roof, huge cypresses lying flat against the brick facade. I have come here directly from the motel after the drive from Florida. For maximum invisibility, I have dressed in all-black clothing: shoes, pants, jacket, itchy ski-mask. I’m being more cautious. The publicity following my arrest outside London Kashmir’s Tampa bungalow has been a wake-up call. Careful preparation is the key.

I have done my homework this time, scouring trade magazines, print-outs from Google Maps and celebrity websites, guide books of all sorts. I know that London Kashmir arrived by private jet at LAX yesterday, a Friday. Monday she begins shooting at Metropolitan Studios for her next film, the international thriller, Optimum Impact, having just completed location shoots in Prague and Niagara Falls. I know too that the light in the second story window shines from London Kashmir’s bedroom. She could be sitting up in bed, studying her lines; she might, at any moment, fling off the covers and pass by the window in stunning silhouette. She doesn’t. But thirty minutes later I’m still watching when the light goes out. I am close enough to see all of the horseshoe driveway. The gate is locked, of course, but there is no one around. It couldn’t be more quiet.

I take a deep breath and, with a little run and jump, scramble to the top of the fence. I’ve just gotten my arm over when an alarm sounds, the area flooding with light. (There was nothing in my research about a fancy security system.) I drop back down and start running. Immediately I encounter a shadowy figure on the sidewalk, sprint past it and continue to my car at the end of the street. Behind the wheel of the Impala, I turn left onto Sunset Boulevard, heading west.

I remove the ski mask. I’m beginning to breath normally again when I notice a pair of headlights in the rearview mirror, headlights content to remain at the same distance, no matter how much I de-accelerate. It’s a slow-speed chase. We cruise past the UCLA campus, through Brentwood and Pacific Palisades, past The Lake Shrine which boasts “beautiful gardens that contain the ashes of Mahatma Gandhi.”

I’ve had enough of this. I pull over at the next street lamp; he pulls over. I’m walking back to his car as he’s opening the door.

“What do you want? Who are you?”

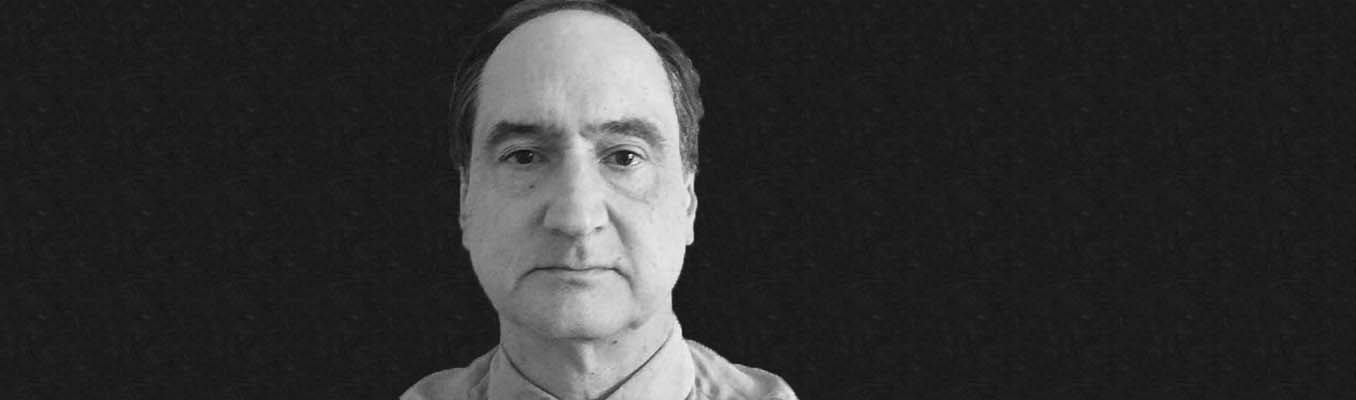

He peels off his knit cap. He’s a she with short dark hair and close-set eyes, a moon-face. She wears frumpy-looking slacks and a grey sweat shirt. One of her black, high-top sneakers is untied.

“Was that you back there?”

“I guess you won’t try that again, huh, Chuck?” she says.

“How do you know my name?”

“Everybody knows your name. You were arrested in Tampa for trespassing on that actress’s property. You have a thing for her and nothing can keep you away from her. You’re famous.”

“You need to go home,” I tell her.

“I followed you all the way from Miami. I just got here.”

“You followed me from Florida?”

“Yeah.”

“I don’t believe you.”

“Your first day out you got as far as Shreveport where you spent the night in a Super 8. You had breakfast at Hardees and drove all the way to Allen Reed, Texas, where you ate lunch at Tastee Freeze–a Big Tee Burger and chili cheese fries. Then you drove nonstop to L.A. And here you are.”

She looks extremely pleased with herself.

“I don’t appreciate being spied on,” I say.

“It’s not spying.”

“Stop following me. I have business here. Important business. Go back where you came from. I mean it.”

She doesn’t move, so I do.

She gives me a flirtatious wave.

“Stop that.”

She blows a kiss.

***

I sleep fitfully, but I haven’t needed much sleep since falling for London Kashmir whose poise and grace and exotic loveliness have a renewing effect on me, make the prospect of seeing her, the merest glimpse, all I need to roust me out of bed; that and the confidence that given a few minutes of her time I can convince her of my sincere devotion. I understand her reluctance to meet me. I have not pursued her by the usual means. If she were a normal person I could simply introduce myself and ask her out on a date. It is her success, ironically, that is keeping us apart.

I know what they say about me, the newspapers, the magazines, tabloid TV. He’s obsessed. He’s dangerous. He’s insane. I am none of those things. What I want is not what’s generally supposed. It is not sex, though I don’t rule that out as a possibility. I want to sit with London Kashmir in some quiet cafe, just the two of us–our elbows up on the table, mugs of steaming coffee between us, no bodyguards, no flunkies–and talk, just talk. Is that so much to ask?

I shower and shave. Before leaving the motel I don fake mustache, sunglasses, baseball cap. I look like any local yokel when, as dawn is breaking, I arrive back on North Roxbury. Since London Kashmir doesn’t begin shooting until Monday, she’ll be on an irregular, laid-back schedule–plenty of holes in it. There could be a repetition of that afternoon in Key West when, accompanied by only one bodyguard and her goofball boyfriend of the moment, the rocker with the tattoos and the nose ring, I followed them from boutique to boutique, then to the park, then to Starbucks, drawing so close at one point I overheard her ordering a skinny latte from the awestruck barista before I was manhandled by her bodyguard.

A tan Escort pulls up beside me. It’s that girl again. She leans over the seat and makes a cranking motion.

She holds out a bag from Designer Donuts, Favorite of the Stars. “I thought you might be hungry.”

“What are you doing here? I told you to go away.”

“Take the donuts. You need to keep your strength up.”

I do. It’s the only way to get rid of her.

“I like your disguise,” she says, and drives off.

Not long afterwards, a limousine appears in the horseshoe driveway. A man in livery places a suitcase in the trunk. At the exact moment the mansion’s door starts to open one of those double-decker tour buses that prowl the neighborhood blocks my view. As it pulls away I see the limousine moving toward the exit, the automated gate swinging open. I can’t make out her face, but in the back seat is a woman wearing a lavender headscarf, and lavender, I happen to know, is London Kashmir’s favorite color. The limo turns right, picks up speed. I make a rapid U-y.

The limo makes two quick stops before leaving the neighborhood, picking up two men and one woman–the usual anonymous hangers-on–with their own pieces of luggage. Soon we’re fighting lunch-time traffic on Hollywood Boulevard. Our little caravan continues west on Sunset, barely keeping to the speed limit. We rush to the end of town, bidding farewell to The Mahatma’s remains. I’m a good eighth of a mile behind the limo, more evidence of the new caution, when the limo turns onto Pacific Coast Highway in the direction of Santa Monica and Venice Beach.

On highway 5, we zip past Yorba Linda, Garden Grove and Huntington Beach, “the largest stretch of uninterrupted beach front on the West Coast.” Twenty miles from Laguna Niguel, the limo turns left onto a two lane road, headed inland. The road narrows and we’re in a flat, sparsely populated area, passing the occasional beach house. Wherever she’s going, some inner coastal resort or secret residence, I foresee a moment when, weary of the sucking up from her entourage, she sneaks off for a solitary walk in a nearby glen. She crosses paths with a mustachioed gentleman in his mid thirties. They strike up a conversation. She feels totally at ease with this stranger who–

The engine is sputtering. The car is losing power. Fighting with the steering wheel, I manage to pull onto the narrow shoulder. I bring my fist down hard three times on the steering wheel as the limo vanishes around the next turn. I may have broken it, my hand, but for sheer agony, it’s no match for the disappointment I feel. I look around and see nothing but tall grasses bending in the wind.

The tan Escort pulls up beside me.

“Need some help?”

I get out of the car and look under the hood, aware that I’m just going through the motions. This isn’t the first time the Impala has broken down, but it’s the last.

“We passed a gas station a minute ago,” she says. “Maybe you could get a tow.”

“This clunker’s done for.”

“So what do you want to do?”

“I want you to drive me back to Beverly Hills.”

“Awesome.”

We’re on the main highway. “Watch the road,” I say, uncomfortable with her staring.

“Sorry. I just can’t believe you’re here. Sitting right next to me. It’s my dream come true. Aren’t you going to ask my name?”

“No.”

“Marian. Which I hate. I go by Stevie. Did you like the donuts?”

“Watch the goddamn road.”

I’ve been with her long enough to appreciate that she’s not unattractive. On the short and dumpy side, perhaps, but her short dark hair sets off nicely her round, pretty face, her small mouth and pouty lips.

“How old are you?” I ask.

“Twenty. Next month.”

“Jesus.”

“Don’t you like younger women?”

I complain again about her staring.

“I can’t help it.”

“So take a picture.”

“I don’t have to. Check the glove compartment. Go ahead. Open it.”

The glove compartment is crammed with computer printouts of articles published about that thing in Tampa, many with the same two or three photographs of me being taken to and from jail, as well as full-color pictures of my mug shot, both face-on and in profile.

I forget and close the glove compartment with my injured my hand. “Fuck.”

“You should have a doctor look at that.”

“I’m not worried about it.”

“Well, I am.”

“Why?”

“I care about you.”

“That’s ridiculous.”

“No, it’s not. She’s not real, Chuck. Movie stars aren’t real. London Kashmir isn’t even her real name.”

“I know that.”

“I’m real. My feelings are real.”

We arrive at my motel–The Essex, single Rooms, $14.99. I step out of the car. She turns off the engine.

“You can’t park here,” I tell her as she’s opening her door.

“Why not?”

“You don’t have a room. You have to have a room to park in the lot. It’s against the rules.”

“Since when do you care about rules?”

“And you’re not coming in.”

“I’ll wait.”

I retreat to my room. I need to see her. I have my own printouts, but they are not stuffed higgledy-piggledy into a glove compartment. They are neatly arranged in three leather-bound scrapbooks. I spread them out on the bed. There is Paperview in this flea bag but I maxed out my Mastercard months ago, which is too bad because they have Isn’t It Romantic?, one of London Kashmir’s earliest screen appearances, a turkey, yes, but saved for me, saved for anyone with a pulse, by the famous hot tub scene and the water soluble bikinis.

I go back out to the car.

“You have a credit card?” I ask her.

“I have two.”

I wave her inside.

Since she’s paying I can’t very well not invite her to watch the movie. She has bought cokes and a bag of chips from the vending machine outside the rental office. We sit on the queen sized bed and pass the bag back and forth, wiping our greasy fingers on the bedspread.

“Not bad,” she says.

“A little stale.”

“I mean the movie.”

“She got better.”

“I don’t know. I prefer her in this sort of fluff to all those stupid melodramas.”

“She was great in Star Crossed.”

“If you say so.”

“She was nominated for an academy award. Do you mind?” She has been moving progressively closer to my side of the bed. She slides back over.

“She went against type in Star Crossed,” she says. “That’ll get you a nomination every time.”

“Don’t you have better things to do?” I’m suddenly angry at this intrusion into my life. “Don’t you have friends?”

“I can’t stand people my age. They’re so surfacey.”

“What about a home? Aren’t your parents worried about their little girl?”

“My parents don’t give two fucks about me.”

“What about boyfriends?”

“Dopey little boys who don’t know their ass from their earlobe. Who needs them?”

“What have you got? A father complex?”

“What have you got? A celebrity fixation?”

She’s quick. I’ll give her that.

“I’ve been thinking,” she says. “London Kashmir could return from the coast as early as tomorrow morning. I suggest we get to the mansion right at dawn.”

“I don’t want you there.”

“You have no wheels, remember?”

London Kashmir is climbing into the hot tub wrapped in a turquoise towel.

“Could you leave now?” I say.

“Why?”

“You irritate me.”

“Have you noticed you never call me by my name? It’s Stevie, in case you’ve forgotten.”

“Get out of the car.”

“I’ll be right outside if you need me again.”

“Beat it!”

***

I’m up before dawn. She’s lying across the front seat of her car, sound asleep. I don’t need her “wheels.” It takes me less than an hour to walk to the mansion. No one’s home. I watch the sun rise. Hours pass. By late afternoon I’m starving. I walk down to North Highland and enter Designer Donuts, Favorite of the Stars. I climb up on one of the cracked leather stools and order a cruller and large orange juice. Except for one wall crowded with framed and signed eight-by-ten glossies, there are precious few movie stars here.

It’s getting dark when I return to the mansion and find all three floors aglow with starlight. The limo is parked in the horseshoe driveway.

“How’s it going, Chuck?”

I gasp.

“Sorry,” she says. “I’ve been watching her for you. She got back an hour ago. You want to sit in the car? It’s right down the block.”

“No.”

“You can’t stand out here. If they see you this time of night they’ll call the cops.”

She’s right.

We go to the car and she pulls within a fifty feet of the mansion.

“How’s that hand?” she asks.

“Couldn’t be better.” Actually, I’m finding it difficult to make a fist.

“So which room is hers? Which bedroom?”

“I have no idea.” I do, of course.

“Too bad about the fence. Otherwise you could hop right over and invite yourself in for cocktails.”

“Shut up.”

I’m trying to catch any shadows flitting by the second story window when all the first floor lights go out, and a minute later the second floor lights. The whole house is dark.

“You know how she got her big break, don’t you?” she says.

“Make Room For Dreamers.”

“That came after.”

“After what?”

“Don’t tell me you haven’t seen those pictures on the Internet.”

“She was a teenager. She didn’t know what she was doing.”

“She looked like she knew what she was doing to me.”

I reach for the door handle.

“Wait,” she says. “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have said that. Look, I’ll get you back here before she leaves in the morning. Five, six, whenever you want. If you let me sleep in your room–the floor, don’t worry. I’ll even let you drive.”

Reluctantly, I agree. When I turn the lamp off at midnight she’s lying in a corner of the room with her head on a pillow. I doze off. I don’t know for how long. The room suddenly fills with light. She has left the bathroom door open, her naked body backlit. She glides towards me.

“What are you doing?”

“What’s it look like, Chuck?”

She continues on to the bed. I give her a shove. She staggers backwards and hits the wall. Sliding down, she curls into a tight ball, her hands covering her face, sobbing.

“When I get back here you better be gone,” I say. “Did you hear me? I mean it.” I slam the door on my way out.

In takes me forty-five minutes to walk to Metropolitan Studios on Gower Street. It’s seven-fifteen and I assume London Kashmir is already on the premises. Twenty feet from the entrance gate, I note the intermittent stream of vehicles passing through the studio entrance. Whenever a car approaches a uniformed guard leaves his kiosk and checks the driver’s ID before raising the security gate. I reduce the distance to the gate to fifteen feet, still unclear about how I will get past the guard. A green Jaguar drives up to the gate. The guard raises it and then tips his hat (a major star, presumably). The gate remains up. The security guard has disappeared from sight. Either he has neglected to push the button or the gate is stuck. Has he gone in search of a mechanic? Is he looking for his contact lens on the kiosk floor? Whatever the case, I stride quickly past the kiosk and into the complex.

All the buildings look the same, bunker-like structures with NO TRESPASSING written across their metal doors, no doubt all locked. I approach an old guy pushing a wardrobe cart and ask if he knows where they’re filming Optimum Impact.

He jabs his thumb at the building behind us.

I hurry over. Just as I reach the door, it begins to open, a man in work clothes stepping out and holding it for me. Luck is with me today. I enter the lobby where two signs are posted, one directing the visitor to the movie sets, the other to the dressing rooms. I choose the latter and start down the long, wide, corridor. At the other end, a woman rounds the corner and moves toward me at a brisk pace, a woman I would know anywhere, at any distance. Dressed in a short silvery dress with matching pumps, her long black hair falling to her shoulders, she holds a sheath of papers in her left hand, what I assume is a movie script. Nothing stands between us. We are alone together at last.

My throat is so dry I can barely speak. “Ms. Kashmir? London?”

She looks up from the script.

“If I could have a moment of your–”

She screams and turns back down the corridor.

Running out of her heels, she throws horrified looks over her shoulder like a maiden being chased through the forest in a teen thriller. She can’t hear my reassuring words over her screeching. She rounds the corner and stumbles, barely avoiding a fall. She tries running again, but her hosed feet are slippery on the carpet. Desperate for traction, her legs pumping wildly, she screams. I let her go.

I’m heading dejectedly back up the corridor when I hear,

“There he is!”

Two heavy-set men with shaved heads and weight-lifter arms rush toward me. I take off running.

I don’t remember how I came in and feel like I’m in a maze until I come to the directional signs and the exit, nearly crushing a man in chaps and a stetson as I fly out the door and dash for the gate. Fitter and faster than I am, the men are not far behind. I reach the sidewalk and spot the Escort at the curb. The passenger door swings opens. I throw myself in.

It’s several minutes before I get my breath back. She’s silent behind the wheel. Her eyes are red-rimmed but dry. She merges onto the interstate and points us east.

“Florida?” I say.

“You okay with that?”

“Fine.”

“So,” she says, “did you see her?”

“Briefly.”

“And how’d that go?”

I don’t reply.

The sun is low on the horizon. I put my visor down to reduce the glare.

Reaching past me, she opens the glove department and takes out a pair of sunglasses. “You know what it looks like almost?” she says. “It looks like we’re driving off into the sunset.”

“Almost,” I say.

Traffic is thinning out. We’ve just left L.A County when she looks over at me. “We’ve been going at it all wrong, haven’t we, Chuck?”

“Yes,” I say. “Yes, Stevie, we have.”

John Picard is a native of Washington, D.C. currently living in North Carolina. He received his MFA from the UNC-Greensboro. He has published fiction and nonfiction in New England Review, Narrative, The Gettysburg Review, Iowa Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. A collection of his stories, Little Lives, was published by Main Street Rag.