I discovered Italo Calvino late. But I did discover him. Evidently, it was my time to find his favorite works of literary criticism (Why Read the Classics?), to open up to some fantasy (“The Distance of the Moon”), and maybe to rehabilitate the neo-realist part of him (Difficult Loves) that he may have undervalued later in his writing life. Now, if I could only have a chat with him.

I discovered Italo Calvino late. But I did discover him. Evidently, it was my time to find his favorite works of literary criticism (Why Read the Classics?), to open up to some fantasy (“The Distance of the Moon”), and maybe to rehabilitate the neo-realist part of him (Difficult Loves) that he may have undervalued later in his writing life. Now, if I could only have a chat with him.

The translations in Why Read the Classics? include many essays involving writers of English. Calvino planned this collection before his passing in 1985 and the Twentieth Century authors included are those he revered the most.

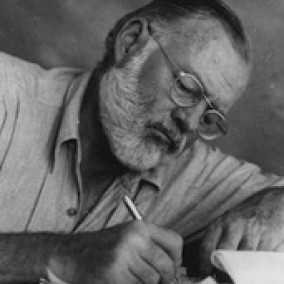

One of the chats I would have enjoyed with Italo Calvino concerns his treatment of Ernest Hemingway. They were a generation apart; but both were journalists; both had seen war up close; and both took an intense, activist—rather than an intellectual anti-fascist stance, Hemingway during the Spanish Civil War and both of them during World War II. And both were authors of compelling fiction.

Calvino and his contemporaries began their writing careers seeing Hemingway as a god-like figure from their fathers’ generation and, starting out as neo-realists, they tried to mimic, or at least learn from, Hemingway. Most of them, Calvino wrote, moved on toward post-modernism after the war, with some (like him) moving into fabulism and fantasy.

Calvino and his contemporaries lived through difficult times “seriously and boldly and with purity of heart.“ They learned from Hemingway to value openness and generosity, practical—technical as well as moral—competencies in doing things that had to be done, and being straightforward. They learned to avoid self-contemplation and self-pity and to learn to gauge a person according to their gestures or handling of brusque exchanges. I would say that is quite a positive legacy if they took all of that from a member of their parents’ generation.

Calvino then explains his generation became more discerning after their first war and found Hemingway’s style had begun to “descend into mannerism.” He came to be seen by them as “too narrow.” They began to know and to think more about his life style, his philosophy of life, and they decided that his focus on “violent tourism,” his hunting and his shark fishing, were repulsive. Not dealt with in the essay is Hemingway’s inability to stay in a marriage very long, but that is such a commonly known fact that it seems implicitly bundled with the critique of his adventure seeking. So, it seems that Calvino and his contemporaries matured enough to have decided after some rumination, that there should have been more to Hemingway. Apparently, it was his reticence about sharing the details of the thinking and range of emotions in his fiction that prompted Calvino’s criticism of Hemingway’s work not having any real depth.

Calvino then explains his generation became more discerning after their first war and found Hemingway’s style had begun to “descend into mannerism.” He came to be seen by them as “too narrow.” They began to know and to think more about his life style, his philosophy of life, and they decided that his focus on “violent tourism,” his hunting and his shark fishing, were repulsive. Not dealt with in the essay is Hemingway’s inability to stay in a marriage very long, but that is such a commonly known fact that it seems implicitly bundled with the critique of his adventure seeking. So, it seems that Calvino and his contemporaries matured enough to have decided after some rumination, that there should have been more to Hemingway. Apparently, it was his reticence about sharing the details of the thinking and range of emotions in his fiction that prompted Calvino’s criticism of Hemingway’s work not having any real depth.

Some biographers and reviewers of them in the last few decades apparently have agreed and have suggested there wasn’t any thinking or any real emotions there in Hemingway to disclose.

I’d have asked Calvino about that. Is that what he was getting at with his commentary?

Did he think there was no thinking or emotion conjured in his own stories in Difficult Loves when he was trying to “apprentice” with Hemingway?

Is it possible Calvino’s criticism might have led astray those biographers who couldn’t or wouldn’t separate life style from the man’s work while mounting their attacks?

It seems to me that in much Hemingway’s fiction, we actually do find ourselves thinking and feeling a good deal about being looked to by other men and sometimes women for a proper response in a tense situation—not discourse, not sharing of emotions, not speculation, but decisive action, maybe even violent action, requiring some physical skill, some mental agility, some grit, and certainly, some control over one’s emotions.

I agree with Calvino that Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories offered us the experience of an apprenticeship along with Nick’s own that resulted in training to tolerate and, if not to understand, to survive as best we can the brutality of the world. It involves identifying yourself (as others will) with the actions you take. It involves a commitment (that you and others can recognize) to manual and technical dexterity so that you can make a judgment as to your utility and reliability to get things done. Like protagonists of Hemingway’s work, you try not to have other problems (or not to show them at least) that interfere with you “doing things well.”

Calvino says there is always something Hemingway is trying to escape. Calvino focuses on Hemingway’s need to keep validating his abilities in doing things well and suggests a sense of vanity about it. Calvino senses in there a desperation, a defeat, maybe a death. Calvino says that Hemingway’s focus on his strict observance of his own code and his apparent application of that code to other things gives it the stature of a moral code. He says that to Hemingway his fidelity and ethical code is the only reality he can be certain of in an unknowable universe.

Maybe to Hemingway, the code is the only thing he can be sure of and he will just have to deal with whatever else comes along. Calvino says this focus eliminates the realities of emotions and thoughts that for Hemingway seem unreachable. I would point out to Calvino that it doesn’t eliminate them as possibilities. It is just that in Hemingway’s world, you don’t talk about it. It is private. Work out your own thoughts and emotions on the subject.

I would bring up to Calvino that perhaps that focus doesn’t eliminate the thoughts and emotions for Hemingway—or for us—and that he, Calvino, in the same essay provides us with the explanation: Hemingway’s first rule was understatement. He doesn’t often mention the details of his thoughts or emotions or what he thinks of those had by others. That is not the way of men involved in any dangerous or grisly business that has to be done—to chat about it, to reflect on it. So, perhaps he, Hemingway the narrator, is still too much a part of the action for Calvino.

I would have asked about “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” and “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” and whether he felt the thinking and emotions of all three characters in the former and of Harry the writer dying of gangrene in the wilds in the latter were not explicit enough.

Calvino says outright that Hemingway’s identification of men with their actions and determining whether or not they are able to cope with duties imposed on them is still a valid way of “conceiving of existence.” I’d have to point out that is still true in a time when women are included routinely in the ranks of firemen, policemen, and combat soldiers.

In a following essay on Jorge Luis Borges, Calvino follows Borges’ discussion about discovering patterns in perceptions which have to be recognized before one can choose a path with this caution: “Yet it is in the rapid instant of real life, not in the fluctuation of time of a dream nor in the cyclical or eternal time of myths, that one’s fate is decided.”

And so it is, I would say to Mister Calvino. And it is particularly true in the realm of Newtonian physics applied to the real world of cars, ships, planes, and firearms. Mister Newton is very unforgiving of neglect or incapacity. Calvino’s essay on Conrad discusses difficulty in writing about the “sense of integration with the world that comes from a practical existence, the sense of how man fulfills himself in the things he does . . . that ideal of being able to cope, whether on the deck of a sailing ship or on the page of a book.” Would Calvino accept Hemingway as succeeding as well as Conrad in writing about that?

Calvino acknowledges his debt to Hemingway in the writing of his own early neo-realist years and he says, in spite of his detracting comments, the ledger is still in the black for Hemingway. He also notes that Hemingway knew how to live in a world with “open, dry eyes, without illusion or mysticism, how to be alone without anguish . . .” He developed a style that “can be considered the driest and most immediate language, the least redundant and pompous style, the most limpid and realistic prose in modern literature.”

Calvino says when he reads Kafka, he finds himself constantly approving and rejecting the legitimacy of the adjective Kafkaesque that we hear and read all the time.

I would bring up to Mister Calvino the eddy currents he has brought to the conversation in writing classes and writers’ groups where some are tempted to use the adjective Hemingway-esque. Some of them deliver it with a sneer, seemingly knowing something, and other still deliver with approving awe.

For those eager to discuss Hemingway, Italo Calvino has fed both sides quite well.

Richard Perkins is a regular contributor to The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review and a graduate of The Johns Hopkins University MA in Writing Program. He is writing an historical novel and revising a collection of connected stories.