Parting is all we need to know of hell. –Emily Dickinson

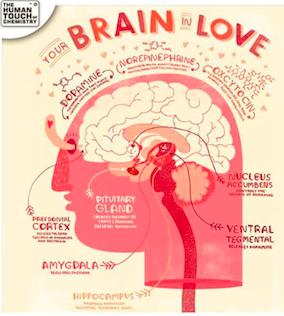

Among all of the emotions we can have, love is one of the most exhilarating and powerful. Hormones associated with love include dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin, adrenaline, vasopressin, testosterone, and estrogen—all of which are part of the brain’s reward system and are responsible for regulating passion, motivation, and sex drive. [i] Writing is or can be a type of love.

In her TED* talk “How We Love” (2014), anthropologist Helen Fisher likens love to cocaine addiction, claiming the hormones involved are part of the “reptilian core” and stimulate wanting, motivation, focus, and craving. Love, Fisher believes, is one of the most addictive substances on earth and, like hunger or thirst, almost impossible to quit. [ii] While we can’t force ourselves to fall in love with writing, we can learn a lot from our body’s response, including how to simulate those responses in order to improve our writing practices.

What if you could harness the passion associated with romantic love and apply it to your writing practice? Writing would become your obsession, your focus would skyrocket, and you’d get so much more done!

The brain is motivated by love because it operates on a reward system. Try giving yourself rewards for writing, starting small, with the pleasure sensors. Buy specialty chocolate, which helps the body release serotonin; licorice, which helps release estrogen; shellfish, which has been linked to an increase in testosterone; or other delicacies; and give them to yourself as a reward for writing.

Love involves more than just physical pleasure. Helen Fisher also postulates that there are three stages of love: lust, attraction, and attachment. Each stage is driven by different hormones and chemicals.

Stage 1: Lust – involves the sex hormones estrogen and testosterone (in both men and women)

Stage 2: Attraction – involves the neurotransmitters adrenaline, dopamine, and serotonin

Stage 3: Attachment – involves two major hormones: oxytocin and vasopressin

She goes on to say that love is part of human chemistry, deeply embedded in the brain, and can be awakened at any time. She calls romantic love a “mating drive” that allows you to focus and conserve energy.

The three stages of love can also be applied to our relationship with writing.

Lust: You can’t resist writing. You may not know the direction you are headed, but you know you have to write.

Attraction: You want to learn more about the craft of writing to become a better writer. You join a community of writers and keep writing.

Attachment: You long to be repeat the process of being published, gathering a following, and making a contribution

When you’re ready to move on to stage two with your writing process, attraction, you’ll want to set clear goals and regularly achieve them. This triggers dopamine, “the reward molecule,” which is more prevalent in extroverted people who have uninhibited personality types. [iii] Start with goals you can easily achieve, write for five minutes every day, and gradually up the ante. Experimenting with outrageous styles and techniques or writing in unexpected places, such as on a rooftop or under a tree, can trigger a dopamine response as well.

In the final stage, attachment, couples form deep bonds that allow them to sustain their relationships. Further along in her TED Talk, Fisher claims that after 25 years of marriage, the same regions for intense romantic love are still active in partners’ brains. Cultivating this bond with your writing practice will take time, but you can create conditions that will facilitate a long-term connection.

Studies show that the hormones oxytocin and vasopressin accompany physical touch and intimacy. Writers can provoke the release of these hormones by forming connections within a writing community. Write in a group setting, share your struggles and offer praise. Having another human being to whom you can give affection will increase your oxytocin and make writing more sustainable in the long-term.

Finally Fisher also discusses anthropologists who have found love in 170 societies—which is to say that they’ve never found a society without love. Love is one of the most natural and invigorating processes our bodies undergo. Harness the power of love, apply it to your writing process, and cultivate a euphoric response every time you put pen to paper.

* TED is a nonprofit devoted to spreading ideas, usually in the form of short, powerful talks (18 minutes or less). TED began in 1984 as a conference where Technology, Entertainment and Design converged, and today covers almost all topics — from science to business to global issues — in more than 100 languages.

Image from http://www.eoht.info/page/Neurochemistry?t=anon

[i] “Neurochemistry.” (Aug. 28, 2014). Hmolpedia: An encyclopedia of human thermodynamics, human chemistry, and human physics. Retrieved from http://www.eoht.info/page/Neurochemistry?t=anon

[ii] Fisher, H. (2014). How we love. TED Radio Hour. NPR. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/2014/04/25/301824760/what-happens-to-our-brain-when-we-re-in-love

[iii] Bergland, C. (Nov. 29, 2012). The neurochemicals of happiness. The Athlete’s Way. Retrieved from http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-athletes-way/201211/the-neurochemicals-happiness

Debbie spent 30 years as a registered nurse. She became a certified applied poetry facilitator and journal-writing instructor in 2007. She is currently a student in the Johns Hopkins Science-Medical Writing program. Her publications have appeared in Journal of Poetry Therapy, Studies in Writing: Research on Writing Approaches in Mental Health, Women on Poetry: Tips on Writing, Teaching and Publishing by Successful Women, Statement CLAS Journal, The Journal of the Colorado Language Arts Society, and Red Earth Review.

A library is a place where you can lose your innocence without losing your virginity.

A library is a place where you can lose your innocence without losing your virginity.