MANEKA | FIELD MOUSE

WITH SPRING SILVER

SONGBYRD PRESENTS

UPSTAIRS, ALL AGES

DOORS: 8:30 PM // SHOW: 9:00 PM

FREE RSVP

Tuesday September 10, 2019

—

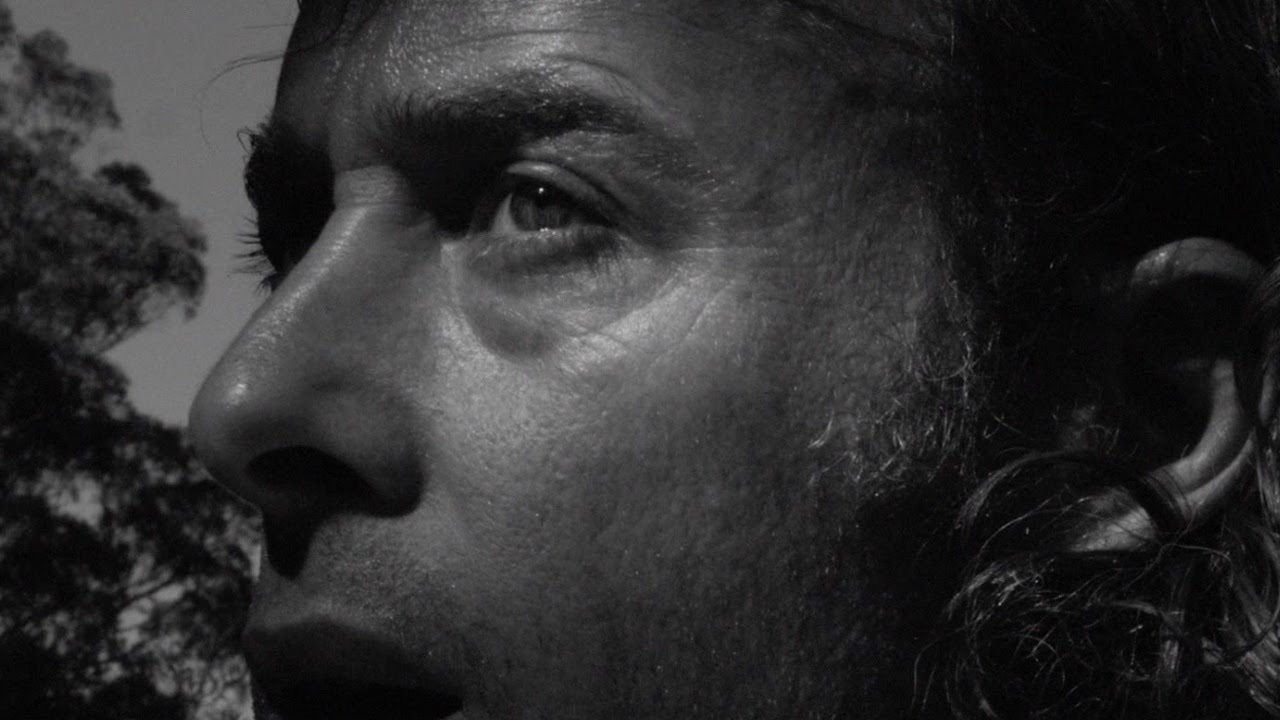

Maneka’s debut LP is a release that attempts to encapsulate the experience of one of the more distinct and multifaceted performers currently making guitar music. That experience is a deep and varied one, and one that is influenced by McKnight’s unique cultural background in a number of ways. Raised in the DC area to a black father and a mother of Chinese and Pakistani descent, McKnight first fell in love with rap and hip hop in his early teens, but was influenced by his older brother, a fan of early ‘90s rock bands like Sonic Youth and Nirvana, and his father’s passion for jazz guitar playing, which McKnight went on to study at Berklee School of Music in Boston. His interests have remained omnivorous, but throughout his life and musical career McKnight has felt as though his musical interests have been consistently policed along racial lines.

“If you’re into rock music and you’re black then people on all sides will say you’re trying to be white or you talk white,” McKnight says. “What does that even mean? That will take over your identity in a big way. Suddenly just because I’m interested in something else that erases all of the other stuff that I’m into. It’s an uncomfortable thing that I shouldn’t have to deal with but that I deal with any way. I’m here and I listen to some music that some white people listen to but that doesn’t mean that I don’t know who I am, or that I’ve erased this other part of me.”

Devin, which nods to genres as varied as grindcore, jazz, shoegaze, hip hop, new wave and post-punk (sometimes within a single song), is in a sense his response, a celebration of McKnight’s identity as a musician and a person and an exercise in what McKnight describes as “claiming a different voice.” Thematically the album digs deep into the corresponding territory of McKnight’s experience as a musician and a person of color in America, exploring a perspective that is rarely represented in indie rock. McKnight characterizes the LP as a “confrontational” album about “black pride and addressing my confusion as a minority in white indie rock scenes,” which is manifested in a variety of ways. The alien punk of “My Queen,” which features McKnight’s Speedy Ortiz bandmate Sadie Dupuis, imagines the relationship between King Tut and Nefertiti, who McKnight describes as “the worlds greatest black Power couple before the Obamas.” “Mixer” addresses McKnight’s sometimes confusing experience of exploring his identity as a mixed race man in a society that constantly interrogates him about his background, while the almost Pavement-esque “Holy Hell” was inspired by McKnight’s move into a new apartment building in a gentrifying neighborhood in Brooklyn, and examines McKnight’s experience as a “gentrifying person” in contrast to the neighborhood’s other residents (“a lot of people set their shit down in the middle of Bed Stuy and are just like ‘this is where I live now,’ but for me it’s a little more complicated” he says). According to McKnight, his embrace of this thematic direction is reflective of the lessons learned over the course of his career so far, particularly the experience of being in a band with the profile of Speedy Ortiz.

“I kept hearing more and more about how me being in Speedy Ortiz effected a lot of people of color just by being a guy up there who looks different than most everybody else doing it, and that really inspired me,” McKnight says. “Rock is such a murky area for a lot of people of colour, especially black people. In a lot of ways I think black people resent rock music because of its appropriative qualities and the feeling of not being welcome. There’s no one else like you being represented. When I see more black and brown faces in the crowd and that makes me feel a lot better about what I’m doing and that I can actually speak to that experience. I’m not making art for art’s sake any more. I have to talk about my identity and my experience or I feel like I’m short changing people. I’m no longer ashamed or afraid to talk openly about difference and how that has either held me back or how that’s misinformed my self image in the past.”

McKnight’s time in the music scene has influenced the album in other ways, perhaps most significantly by introducing him to the community of musicians that he now turns to for inspiration and council. It features contributions from several people in that community including longtime Maneka drummer and vocalist Jordan Blakely, producer Mike Thomas of Grass Is Green, members of Stove, Ovlov, Speedy Ortiz and Two Inch Astronaut, and McKnight’s cousin, the award winning saxophonist Brent Birkhead. The track “Positive” functions as a kind of song of encouragement to his fellow musicians, many of whom struggle with mental health issues, and McKnight’s writing process for the album was partly born from his friendship with (Sandy) Alex G, which blossomed during time they spent on tour together.

The results are consistently engaging, surprising and something that could only have been produced by McKnight. From the album’s metal-inspired opening – a track (named in homage to the trick plays run when McKnight was a high school football player) on which he demonically recites a recipe for chitlins as a way of re-appropriating the use of the devil in metal music to dramatize the ways the legacies of slavery still effect the black community today – to the intimate closing track “Style,” a soundscape that incorporates a recording of his parents talking about him (“you’ve got your own style, Devin,” his mother says. ”…it’s different, it’s not the same as every person…we have to embrace that”), the album is an incredibly personal document that succeeds in communicating, with depth, clarity, humor and emotional directness, the experiences that have made Devin McKnight who he is.

“Jumping around between genres and styles and claiming a different kind of voice, taking these liberties, I was uncomfortable about that,” says McKnight. “A friend of mine convinced me that being able to show those different sides and take on those different voices is a good thing, he convinced me that I should celebrate that. He said ‘that’s the beauty of being you. The beauty of being you is that you don’t fit the package.’”

—

Field Mouse

Rachel and Andrew formed Field Mouse sometime in 2009 after meeting at SUNY Purchase. After releasing two 7″ singles, they signed to Topshelf Records and released their first full length Hold Still Life (2014) followed by Episodic (2016). Their new album, Meaning, comes out August 16th, 2019

MUSIC VENUE

Our venue — lovingly referred to as “THE BYRD CAGE “ — is the new premier space to experience live music in Adams Morgan. Featuring a state of the art sound system designed by Audioism and a funky basement vibe, it has a standing room capacity of 200+ and a seated capacity of up to 100. The venue hosts international, national and local artists, from live performers to DJs, as well as other live performance art forms.

RESTAURANT AND BAR

Located at 2477 18th Street NW, the SONGBYRD MUSIC HOUSE features a full menu and bar ideal for soaking in DC sounds and flavors with your squad.

Our seasonal food and drink menus cycle to best fit the moods both outside and inside, and the cozy decor makes this Music House the newest destination in Adams Morgan to nod your head, and more. Come by to listen to a DJ spin upstairs in the bar, grab a bite, then head on downstairs the the Music Venue a.k.a The Byrd Cage to listen to a live show, some comedy or to dance.

WEEKDAY HAPPY HOUR 5-7 pm : $2 off all tap, $5 all rail, $8 quesadilla (no takeout)

Saturday 5-7 pm- $8 Hot Dogs (no takeout)

Sunday 5-10 pm- 1/2 burgers (veggie, turkey, and classic beef) (no takeout)

REVERSE HAPPY HOUR every Friday and Saturday starting at 11 pm $5 taps, $4 Coronas and other specials