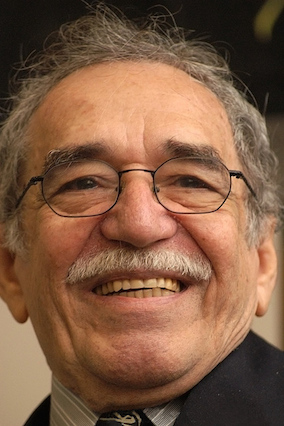

Magical Realist Biographies: Gabriel Garc

GABRIEL JOSÉ DE LA CONCORDIA GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

GABRIEL JOSÉ DE LA CONCORDIA GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

Born: 6 March 1927

Died: 17 April 2014

Little known facts:

Gabriel García Márquez developed his extraordinary premise for his novel Love in the Time of Cholera by adapting the actual tragic comedy of his maternal grandparents’ attempts to discourage the intense courtship of his mother by his father.

His mother’s father explained to him there was no greater burden than to have killed a man, demonstrated early on in One Hundred Years of Solitude when José Arcadio Buendía leaves town with his family and friends after having killed a man.

Much better known facts:

He was known affectionately as “Gabo” throughout Latin America.

Some of his works are set in a fictional village called Macondo—inspired by Aracataca where he was born and raised until he was eight—that provides the location for multiple large-scale magical realist clashes of cultures and civilizations.

García Márquez won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982.

Gabriel García Márquez was one of the great writers in Western literature in the Twentieth Century and perhaps the most celebrated writer of Magical Realism of his time. He often declared he was a journalist who also wrote fiction and, as a consequence, he saw reality as his central theme. In his fiction, Marquez avoided easily discernable plot structures and forced his readers to actively engage in order to derive essential details because, like the dramas of Sophocles whom Gabo admired, much of the action happened off stage. His fiction probes the themes of the violent realities of Colombian history—particularly the War of a Thousand Days (1899-1902) and the Banana Massacre of 1928 that his grandfather experienced and La Violencia (1946-1958) that he experienced—and various forms of solitude found in geographical, political, social, and individual isolation. Solitude was the theme in his acceptance speech for his Nobel Prize, entitled “Solitude of Latin America” and is quoted in part below.

García Márquez said that his early works (that he called a kind of premeditated literature) reflected the reality of life in Colombia and provides the rational structure of his books, though in retrospect he declares it “too static and exclusive a vision of reality.” His later work shows experimentation with alternative means of reflecting and re-reflecting reality, drawing on a story telling style his maternal grandmother used to describe bizarre details “with the deadpan expression.” He is universally recognized as one of the four leaders of the Latin American Boom along with Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, and Mario Vargas Llosa. He consistently acknowledged his debts to precursors like Jorge Luis Borges, Miguel Ángel Asturias, Arturo Uslar Pietri and Alejo Carpentier, Juan Carlos Onetti, and Juan Rulfo.

Gabriel was born in Aracataca in coastal Northern Colombia. His father had dropped out of medical school, had very Conservative views, and had four children out of wedlock before the courtship began. His mother’s father, a Liberal veteran of the War of a Thousand Days was a retired colonel who had actively interfered with Garcia’s father’s courtship of his mother as alluded to above. Despite his profile, his father’s persistence eventually wore down the colonel’s objections and the marriage was allowed, resulting soon afterward in the birth of Gabriel—the first of twelve children.

Gabo lived with his maternal grandparents in Aracataca until he was eight. His grandmother provided him with a deep background of folkloric knowledge including omens, premonitions, dead ancestors, and ghosts—most of which his grandfather dismissed as “women’s talk.” However, the sincere manner in which she told her stories had a lasting effect on the mature writings of García Márquez who used that deadpan style thirty years later in the crafting of his most acclaimed novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude.

When his grandfather died in 1936, Gabriel was returned to the custody of his parents for a short time before being sent to boarding school. Then the Jesuit Liceo Nacional, in the city of Zipaquira near Bogotá, gave García Márquez a scholarship when he was fourteen. He graduated from that secondary school in 1946, intending to prepare for a career in journalism. However, his family insisted Gabriel study law at the National University of Colombia in Bogotá instead. Marquez detested this prescribed field of study and invested himself in writing. In 1947, the literary supplement of El Espectador published one of Marquez’s short stories—the first of ten they would print.

In 1948, Jorge Eliecer Gaitan Ayala, a prominent Colombian Liberal Party member, was assassinated, prompting a decade long period known as La Violencia, engulfing every Colombian, taking the lives of over two hundred thousand, and leading to the departure of over one million Colombians to neighboring countries. In the second year of the conflict, the National University of Colombia closed and García Márquez relocated to the University of Cartagena, continuing his legal studies, writing pieces of journalism, but never completing his degree.

In 1950, Gabriel García Márquez relocated to Barranquilla where he wrote columns for the daily El Heraldo. He lived in a small room in a four-story brothel and consumed literature that inspired his later work: Virginia Woolf, Sophocles, William Faulkner, Franz Kafka, James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway. He wrote his first novella and later revised it as La Hojarasca or The Leaf Storm. In 1955, friends found the manuscript and had it published. That first novella echoed William Faulkner’s gothic tone and complex structure, and it was his first use of the village of Macondo.

.

García Marquez returned to Bogotá in 1954 and found a position at El Espectador as a reporter and film reviewer. Not long afterward, his work exposed government ineptitude and corruption including the wreck of a ship, irritating the Colombian dictator Gustavo Rojas Pinilla. (In 1989, this story was published in English as The Story of the Shipwrecked Sailor.) El Espectador, fearing backlash from the government, sent García Márquez to Europe as a foreign correspondent. While Gabo was in Europe, the government closed El Espectador, pushing him into poverty conditions far from home. Even so, while working days at a survival level, he still spent his nights writing fiction.

In 1957, Gabriel García Márquez finished writing El Coronel No Tiene Quien Le Escriba or No One Writes to the Colonel. He then relocated to Caracas and found work at the magazine Momento.

In 1958, he married Mercedes Barcha Pardo in Barranquilla and left immediately to return to Caracas with his bride. Their first son was born in 1959.

In 1959, García Márquez founded a Bogotá branch of the Cuban press agency Prensa Latina and in 1961, he moved to New York City to work in the Prensa Latina office there. That same year, he traveled to New Orleans and then moved his young family to Mexico City. In Mexico City, he worked as a screenwriter while working on his novels. The newly established Inter Press Service (IPS) news agency recruited Gabo in 1967 to be the Latin American Editor, but soon after the agreement, he arrived at the major inflection point of his life before he could take that position.

In January of 1965, Gabo had been driving his family to Acapulco from Mexico City, turning over in his head a book he had been trying to write about Aracataca—as Macondo. It suddenly struck him that he had to tell the story of Macondo in the same tone with which his grandmother had told him stories. He stopped the car and turned around, postponing the family vacation and going home to isolate himself for the next year and a half writing the story of Macondo while his wife managed the household, kept him fed, and sold belongings to buy him the paper and ink he needed. They had to borrow the money for the postage needed for mailing the final chapters to the publisher in Argentina. That is the scenario played out in generation after generation in Macondo within the Buendía Family in One Hundred Years—a visionary pursuing something elusive backed up by the committed realist who loves him or her in spite of the stumbles along the way.

Then in 1967, that Editorial Sudamericana in Buenos Aires, Argentina, published One Hundred Years of Solitude. It was immediately successful, selling all 8000 copies in a week and one half million in the next three years and leading to international prizes including the French Prix du Meilleur Livre Etranger, the Italian Premio Chianciano, the American Neustadt Prize, and Venezuelan Romulo Gallegos Prize. At the time of his passing, there had been 50 million copies sold in 25 languages.

Gabriel García Márquez moved his family to Barcelona, Spain, continued to write, and by 1973, returned to political activism. He supported many left wing causes in Latin America and, in the process, realigned himself with the Communist Cuban government. This resulted in the United States Department of State preventing him from entering United States without special permission.

García Márquez returned to Columbia in 1974 and created the newspaper Alternativa in Bogotá. He published the novel The Autumn of the Patriarch about a dictator ruthlessly holding on to power in a Caribbean nation.

When Belisario Betencur became the president of Colombia, he asked Garcia Marquez to return and offered him several political appointments, all of which were rejected. He did return home and continued to consider himself a journalist who wrote fiction. To reinforce that, he created the Foundation for a New Ibero-American Journalism in Cartagena, which received UNESCO funds for helping young journalists learn the craft of journalism.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s literary and journalistic work declined after he was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer in 1999. He passed away at his home in Mexico City in April of 2014. By all accounts, he still saw his work as part of a tradition of Latin American literature and considered his Nobel Prize to be a late acknowledgement of the greatness of Latin American literature.

A FEW OF GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ’S QUOTES

“My grandfather the Colonel was a Liberal. My political ideas probably came from him to begin with because, instead of telling me fairy tales when I was young, he would regale me with horrifying accounts of the last civil war that free-thinkers and anti-clerics waged against the Conservative government.”

“Most critics don’t realize that a novel like One Hundred Years of Solitude is a bit of a joke, full of signals to close friends; and so, with some pre-ordained right to pontificate they take on the responsibility of decoding the book and risk making terrible fools of themselves.”

“The country that could be formed of all the exiles and forced emigrants of Latin America

would have a population larger than that of Norway.

I dare to think that it is this outsized reality, and not just its literary expression, that has deserved the attention of the Swedish Academy of Letters. A reality not of paper, but one that lives within us and determines each instant of our countless daily deaths, and that nourishes a source of insatiable creativity, full of sorrow and beauty, of which this roving and nostalgic Colombian is but one cipher more, singled out by fortune.”

A FEW QUOTES ABOUT GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

Carlos Fuentes, Mexico’s greatest novelist, claimed that Gabriel García Márquez was “the most popular and perhaps best writer in Spanish since [Miguel de] Cervantes.”

“He writes with impassioned control, out of a maniacal serenity: the Garcíamárquesian voice we have come to recognize from the other fiction has matured, found and developed new resources, been brought to a level where it can at once be classical and familiar, opalescent and pure, able to praise and curse, laugh and cry, fabulate and sing and when called upon, take off and soar . . .” — NYT April 10, 1988

Juan Manuel Santos, the President of Colombia, described him as the “the greatest Colombian who ever lived” just after his death in April 2014 as reported by BBC.

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ’S NOTABLE WORK

The Story of the Shipwrecked Sailor (1954), No One Writes to the Colonel (1957), One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975), Love in the Time of Cholera (1985)

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ’S AWARDS

1972 Neustadt International Prize for Literature

1982 Nobel Prize in Literature

French Prix du Meilleur Livre Etranger

Italian Premio Chianciano

American Neustadt Prize

Venezuelan Romulo Gallegos Prize

SOURCES

http://www.egs.edu/library/gabriel-garcia-marquez/biography/

http://salempress.com/store/samples/notable_latino_writers/notable_latino_writers_gabriel.htm

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/themes/literature/espmark/index.html

http://www.cnn.com/2014/04/17/world/americas/gabriel-garcia-marquez-dies/

http://www.other-news.info/2014/04/my-personal-memory-of-garcia-marquez/

http://www.themodernword.com/gabo/gabo_biography.html

“A Review of Gabriel García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera,” The New York Times, 10 April 1988.

Nobel Lectures, Literature 1981-1990, Editor-in-Charge Tore Frängsmyr, Editor Sture Allén, World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore, 1993.

Richard Perkins is a regular contributor to The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review and a graduate of The Johns Hopkins University MA in Writing Program. He is researching the background for an historical novel set in Colombia between the world wars not very far from Macondo.