One of my writing students recently asked a question that I think we all ask ourselves. How do I know when my setting or world-building is enough or too much? I love this question because I think we all struggle with this, regardless of form.

Janet Burroways’s Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft (9th Edition), an excellent book on the craft of writing, offers this advice:

Human character is in the foreground of all fiction, however, the humanity might be disguised. Attributing human characteristics to the natural world may be frowned on in science, but it is a literary necessity…. Your fiction can be only as successful as the characters who move it and move within it. Whether they are drawn from life or are pure fantasy—all fictional characters lie somewhere between the two—we must find them interesting, we must find them believable, and we must care about what happens to them. (Writing Fiction)

When struggling with place, setting, world-building, our best guide is the main character(s) within the scene. About what does the character care most? And how does the setting engage with and support the character? This is why fiction writers so often refer to “place” over “setting.” The setting and world-building are essential, but until the character(s) find PLACEment within the setting or world-building, in each and every scene, the narrative will be flat. Even in scene exclusive sections. If the reader cannot imagine her/himself within the setting in some connective way—though character PoV and/or three-dimensional setting details—the setting is damaging the narrative and the reader’s connection with it.

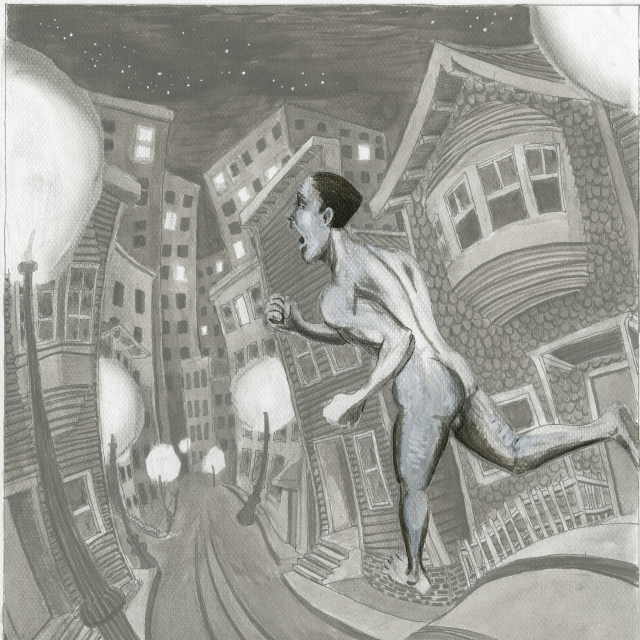

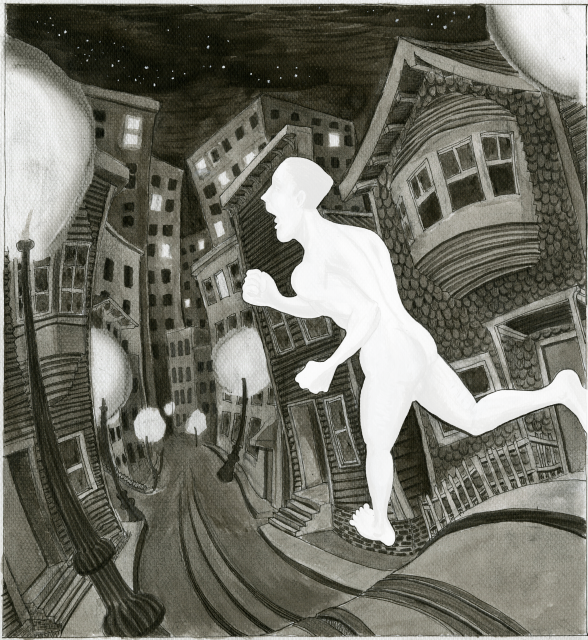

Study the above section of Morgen Eljot’s GW. What do you imagine the character (subject) feels? What do you imagine he is doing? From where has he come? To where is he going? How old is he? What is his occupation? How does he spend his Friday nights? Most importantly, how does this man’s face make YOU feel as you watch him? Are you intrigued about his surroundings? His physical place in the world?

Place and Setting

Setting is the time and place of the action in a work of fiction, poetry, or drama. The spatial setting is the place or places in which action unfolds, the temporal setting is the time. (Temporal setting is thus the same as plot time.) It is sometimes also helpful to distinguish between general setting—the general time and place in which all the action unfolds—and particular settings—the times and places in which individual episodes or scenes take place. (Norton)

Whether we are writing realism, magic realism, fantasy or science fiction, each narrative requires creative “world-building,” just, some more than others. However, no matter the form, the character(s) should always drive the overall development. Still, this doesn’t mean that the setting can’t have it’s “alone” time with the writer.

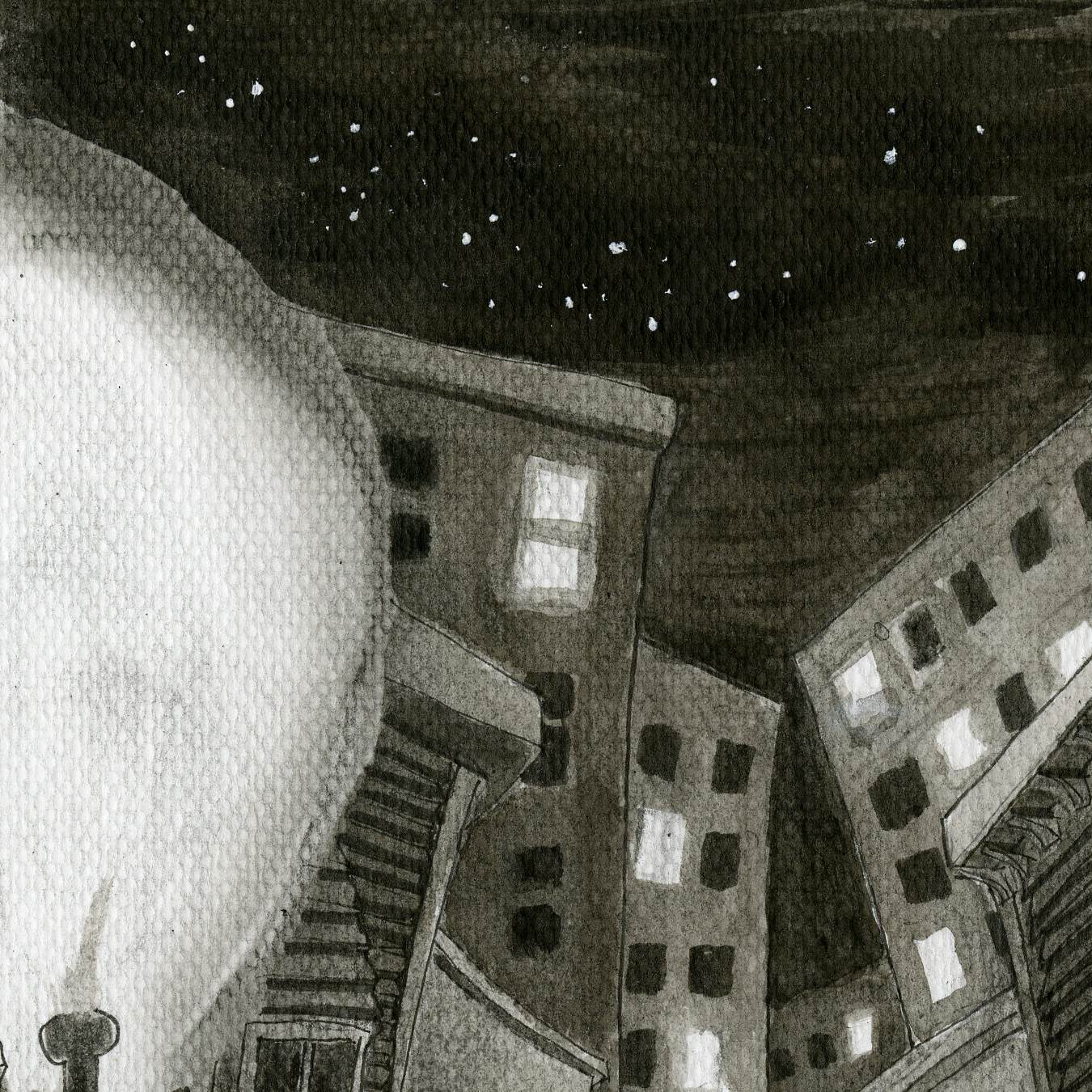

Study the above section from Eljot’s GW. What details in this setting stand out to you? Is it cold? Warm? If you stood in this setting, what might you smell? Is the tone surreal? Ominous? Opportunistic? Now, ask yourself, if any of this matters to the character. Until the narrative has fully developed in character and the character or characters are deeply present within the scene, the setting will be flat, just a backdrop with little or no engagement. Turning any setting into a three-dimensional atmosphere depends upon how much the character or characters are in harmony or in conflict with the setting.

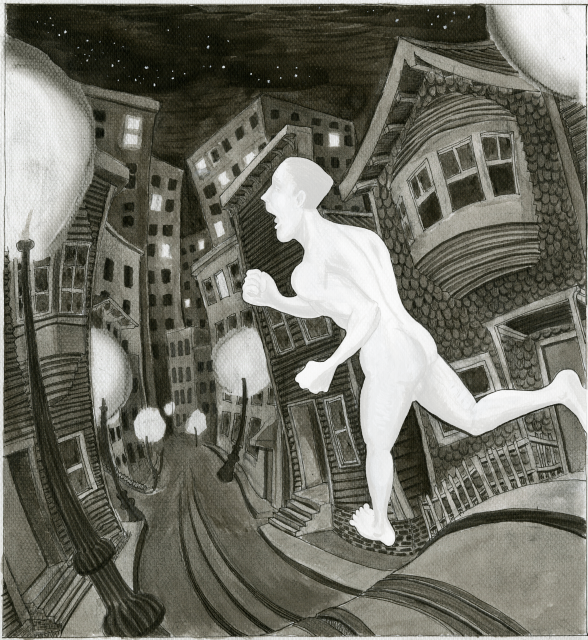

Whether your revisions begin with setting or character doesn’t matter so much. Your revision process is what you need it to be for your work, and it will likely change from one writing project to another, depending upon the narrative’s needs. The primary focus is making sure that the character and setting development within each scene is given isolated, cyclical explorations. Think of the process as weaving a tapestry. In a tapestry, the fibers weave up and over and into each other. Let your characters and settings weave into each other. Give them both texture and dimensionality. If you find, at any time, that the setting is taking precedent over character, such as in the below panels, question whether or not this is what the narrative wants and needs. If character is taking too much precedence, question if the setting might be more fully woven so to further enhance character, conflict and plot progression.

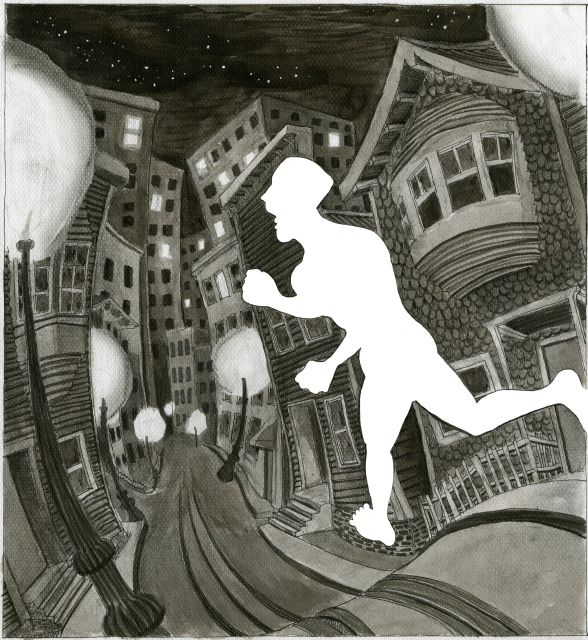

Consider the below panels. Do you currently have any narrative scenes like these panels? Scenes with settings that have great detail, but are taking so much precedence that the character or characters are empty or severely faded in relationship? If so, is the narrative in need of this? If you answer yes to this question, still, consider more fully developing your character’s details and interactions with the setting, first, as an exploratory exercise. If after this exploratory exercise, you still feel that the setting’s precedence over character is essential, you’ll know it for sure rather than guessing. Remember, when writing a story, most of it will be exploratory and then deleted or archived for a later project, which makes it no less essential to the process of that particular narrative.

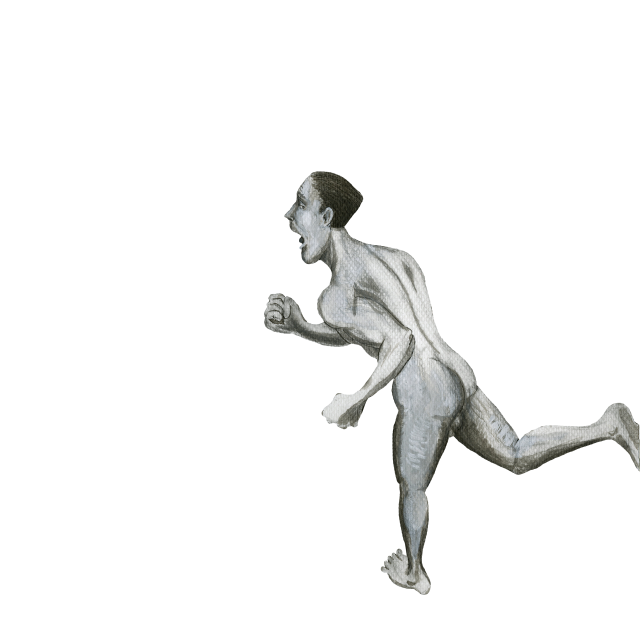

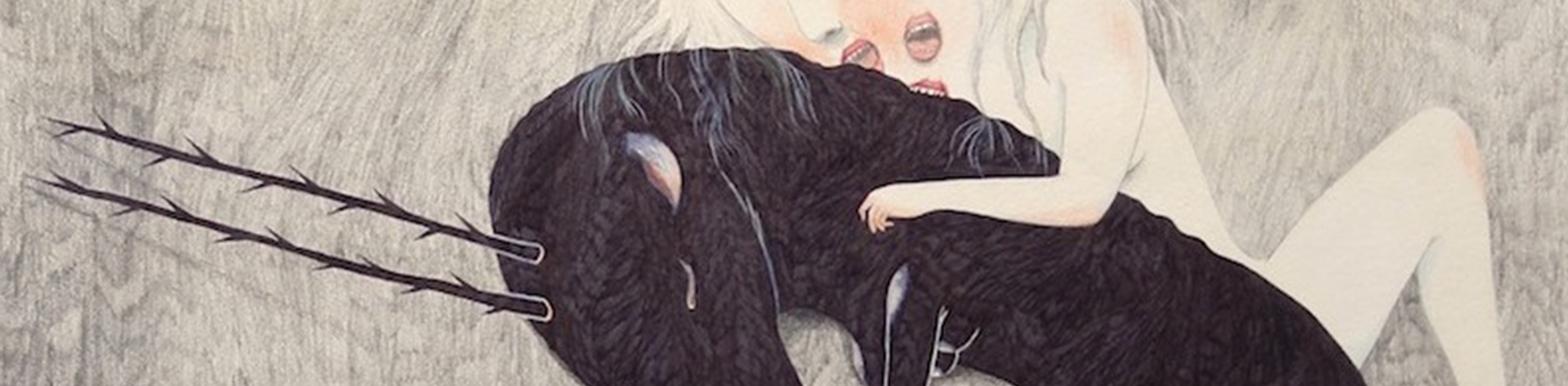

Likewise, as in the below panels, the setting can be absent or faded. A character without it’s place in a well-developed temporal and spatial setting is isolated from it’s fuller story.

Writing Exercise: Character and Setting Details

GW. Panel No. 1: The Missing Character: When reading narratives, readers generally connect more so with the main character(s) within each scene. For this reason, sections that focus only on setting can feel like it has a “hole” in the narrative. How can a scene focused purely on setting draw the reader in so thoroughly that the missing character does not hinder the reader’s connection with the scene? Write a short scene about this setting and make it connective physically and emotionally for the reader.

GW. Panel No. 2: The Faded Character: Faded characters can be more problematic than missing characters. When the setting takes precedence over a flat or faded character, the reader is constantly reminded that there is a character present, but it is “ghostly,” transparent. Can you think of a scene where the faded character is essential to the scene, rather than distracting and hindering? If so, write this scene.

GW. Panel No. 3: The Missing Setting: Character focus within any scene can work very well; however, it’s important to remember that the reader will be anticipating the setting and if setting is withheld for too long, it will become distracting and a hinderance to the scene. When pure character focus is essential to a scene or section, consider not just eliminating the setting, but also closing the frame so that the character fill the entire frame. Write a short scene in which the running man fill the entire frame.

GW. Panel No. 4: The Faded Setting: The faded setting can be as problematic as the faded character. The reader senses that the setting is there, but it’s blurry. This creates a distraction rather than a canvas. If a scene requires intense character focus, less setting focus, one technique is to spotlight the scene based upon the character’s PoV. For instance, in Panel No. 4, notice that the top left window is spotlighted and it is the window that the running man appears to be watching. By fading the rest of the setting and spotlighting the scene’s main character and one or two specific items within the scene, the narrator can create a sense of closeness and detail for both character and setting. Try it. Write a short scene with the running man and spotlighted window. Let your imagination take the scene wherever you wish, as long as your are spotlighting character and one or two items in the scene.

Now, study the two below panels. Notice the shift in framing. In the first panel, the reader is close and focused on the character. In the second, the PoV is wider and less-focused on the character, but rather the entire scene—character and setting.

Writing Exercise: Character, Setting and Point of View

- Let’s try an experiment. Walk into a room. Any room. This we’ll call our “observation room.” For five minutes, study it from the doorway. What do you see? WHO do you see? Smell, hear? Now, for five minutes, walk around and look more closely, touch things, smell them, listen. Try to remember as many sensory details as you can about the entire room. Now, go into another room and write as many details as you can about the observation room and everything you experienced within it. (No cheating. Do not take notes as you study and walk around the observation room.)

- Next, walk into the same room. Choose one person for focus and spend five minutes studying only that person. Then go into another room and write as many details as you can about that person.

Which of the accounts feels most connective to you as a reader? Ask yourself why. Are you more comfortable with “your person” or setting? With which were you able to give more specific detail? Why? How might you further develop your observation techniques with both “person” and setting?

Now, take both accounts, character and setting observations, and weave them together into a single scene. Let your creativity apply whatever details and motivations come to you along the way. As you do this, consider how the “character” focus informs the “setting” focus and vice versa.

Submit for Individualized Feedback