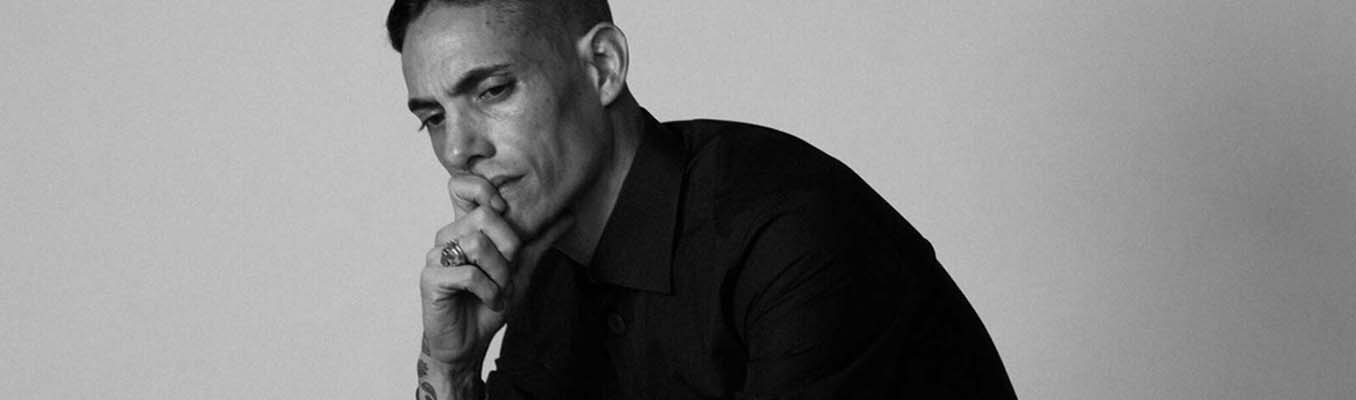

Released this past May by Sarabande Books is Hustle, a debut collection of poetry by David Tomas Martinez. Hustle, spotlights the intersection of race and masculinity. Partially about growing up in an urban environment, his poetry reaches beyond describing life’s difficulties and poetically grapples with structures of power and marginalization. Through his writing, Martinez conveys the fluidity and plurality of identity. But even more so, he gives a poetic voice to experiences that society tends to stereotype, ignore, or completely silence.

Chelsey Clammer: What are the main themes Hustle explores?

David Tomas Martinez: Among the themes Hustle investigates, some are gender, power, race, social class, sexuality; most of the large social structures we navigate on a daily basis. You know, pretty much that thing we call life. That being said, I wasn’t trying to write a book of overtly political poetry because I think it is problematic to begin a poem with a desired intention, particularly a political one. Seriously, a poet beginning a reading with “I have a long sequence of political poetry” makes we want to break out the flamethrower, for multiple reasons. However, I am a person in this world, aware of various pressures social structures exert on my life, so it only natural that my book will have some implied political beliefs. But to combat the calcifying effect of the overly politicized poem, I address the personal, entering adulthood amongst the difficulties in an urban environment, for instance. Honestly though, none of these are really satisfactory. It irks me when I hear others describe my book as “written about gangs, stealing cars, and shooting people.” If Hustle is no more than a voyeuristic jaunt through the ‘hood, then I have done a disservice to the reader and myself by having less than nuanced speakers. I have been pretty fortunate, though, that many people have been very generous with their praise of Hustle.

CC: How do you feel poetry was the best way for you to write about these themes? What about poetry do you feel gave you a better avenue to look at violence and masculinity in a way other genres might not have?

DTM: I don’t believe I was built to only write poetry, so my answer may suggest ambivalence towards poetry. Don’t believe it.

The best poems think us through them, and that is a wonderful moment when you can connect with someone through their words.

But my relationship with poetry is problematic. Firstly, I refuse to view my life through the prism of poet, as if all things happening are experiences for my poems. I am cautious of this crystallization of experience because most of my life has been spent not writing poems, granted, much of my time spent not writing poetry was unhappy, but I would have found something to release the stress and pressure of everyday life, some sort of outlet. Used to be basketball, now its poetry that makes life tolerable. But mostly I don’t view my life as a poem I haven’t written because I believe it’s a horrible way to live, and I refuse to live as a puppet to my poetry. Also, poetry is my job, and that can cause serious problems with a writer’s work. When it is your job, then your livelihood depends on writing good poems, or your happiness depends on writing good poems, which can do some loopy things to a poet’s head. I try and pretend poetry and I are just friends with benefits and not married, though we are. I do this so I can gain some distance from any goals when I write. I guess that’s akin to roleplaying. So far that mindset has worked. However, I really do love poetry, and I am completely encamped in the writing of it. For me, a poem is a finite moment in time, exhibiting some resolution of a problem. The best poems think us through them, and that is a wonderful moment when you can connect with someone through their words. And only poetry does it, usually, quickly. In fits and spurts. In a way that I have often heard called shamanic, magics dance to the chant of a human voice. No other genre of writing captures this phenomenon as well as poetry.

CC: Thinking about masculinity, race and violence, how do you feel your work reveals as well as complicates the intersections of these aspects in our society?

DTM: I’m half Mexican, half white, and I grew up in a predominately black (it was called Lil Afrika) neighborhood, so I never feel fully entrenched in one sort of identity. And though I identify as Chican@ and am interested in the political issues for Latin@s, I like to think I can move with fluidity in many different environments. I am friends with professors and pimps, which can be exhibited in my writing by changes in registers of language, code switching, and vastly ranging allusions; images. Most of the “gang” events I talk about in Hustle are over 20 years old, since those events took place the cross pollination among cultures has increased, in my opinion, which may speak to the plurality some readers identify in the poems. I think Hustle challenges our current interpretation of masculinity by placing the speakers of my poems in difficult situations, where they struggle with the necessity to be strong because of environment or societal and community expectations. By that I mean, I feel that current ideas of gender roles are anachronistic, placing pressure on the men in our society to live up to a standard that may, or may not, reflect their own desires and dreams. Masculinity is strange in that it is completely enveloping of my life, yet there is little conversation about its effects on the life of men, and how this affects the way men treat women in this society. I don’t see many constructive talks, at least. Essentially, because gender roles are unwritten rules, men model their ideas of masculinity by community shaming and adulation, by the men we know, by the image we consume. That can be a very difficult learning curve, and what becomes a byproduct of this process is prejudice based on stereotypes. In Hustle I was trying to give a voice to the young urban minority male because often it is silenced before it has a chance to sound off.

Magics dance to the chant of a human voice. No other genre of writing captures this phenomenon as well as poetry.

CC: What sort of distance did you need from the situations discussed in the poems in order to be able to write about them?

DTM: Distance is very important for my writing process. Distance allows for uncomfortable situations or scenarios in my life to not be subscribed overly sentimental slants of perspective for the speakers of the poems. But there still has to be some emotional resonances, some joint that hurt when it rains for the poems to resonate with the reader, obviously. For instance, in “Forgetting Willie James Jones” I was working through resentment over the shooting of my friend Maurice. At the time, almost twenty years after the fact, I was still angry that Maurice had been completely ignored by the San Diego news media, and that Willie was being memorialized, having streets named after him, and basically sainted. For me the lack attention to the death of Maurice spoke to the muzzling of my community by forces outside of my community. At 17, I didn’t posses the language to understand that my resentment was not with Willie but the lack of empathy for my friend. I also couldn’t process that Willie was valedictorian, wrestled, and had a full ride to Brown, while Maurice was a gang member killed in a gang killing, that’s a gang of gang related issues. I knew that my resentment was wrong, so I set out to write a poem about this time to resolve these issues. Without some sort of distance it would have been impossible.

CC: What was your process for writing these poems? For how long did you work on this collection?

DTM: I seem to be answering these questions, partly at least, a question ahead. I’m starting to really question if I’m not a mutant or something. Professor Mex, if you will. In my process, each poem has a problem and resolution. Now I use this as a very rough analogy, there need not be a fixing of some problem, and the problem can be undeclared, but as reader I better go some damn where. Often I will have some event, or feeling, or catalyst “inspiring” the poem, basically a story I want to tell the reader. Much of Hustle was written in this manner, as I described for “FWJJ.” I also like to read critical and theoretical work that always draws ideas out of me. I do plenty of late night reading of this kind of work. It took about 5 years to write Hustle but my process has sped up exponentially. Most of the time needed was time to emotionally process. My process for new poems takes much less time. Knock on wood.

CC: Are there other poets you turned to in order to see how masculinity was reckoned with in poetry?

DTM: Not really. Tony Hoagland has been a big influence on me as a writer, homeboy, and teacher.

I was trying to give a voice to the young urban minority male because often it is silenced before it has a chance to sound off.

The wrestling to define masculinity in Tony’s writing was such a huge influence on me that I tried to take a slightly different approach. I was not going to be eaten by that cucuy. To be honest, theoretical work was really a much larger influence on me than any one writer, and thinkers, such as bell hooks, greatly influenced how I think about masculinity and race. I really am a big fan of her. Though now that I think about it, Campbell McGrath influenced me with his use of form and the way he talks about man shit. So did Hoagland and McGrath. Tupac, too. Well I guess I lied because I start with none influenced my thoughts on masculinity then name four. Well you know what they say, “there are two rules for success: 1) Never reveal everything you know.

CC: Your publisher, Sarabande, provides a reader’s guide for your book. How do you see your collection being used in an educational setting?

DTM: Students have responded very positively to Hustle. Plenty of high school and college students have told me they don’t like poetry but they liked my book. I don’t really know how to take that. Optimistic dtm thinks, *damn I must have wrote the book of my generation. I knew I was getting canonized.* But pessimistic dtm thinks, *you just wrote a book that people who don’t like poetry like. You are Billy Collins. Your career is over.* Did I just use the third person? Yes dtm did. Anyways, there are also practical reasons for writing a teaching guide, sales. I try to be practical about these things and grind to help out Sarabande because they have been really great to me. I did tattoo the logo on my wrist.

CC: What are you working on now?

DTM: I’m thirteen pages into a new manuscript. The new poems have personal elements and stories but the associative nature make them less dependent on one defined setting. Highly associative leaps are in Hustle, but the new manuscripts pushed jump further in their associations. Poems from this manuscript have been published in Poetry and Oxford American, so I feel like I am off to a very strong start. I edit Gulf Coast’s Reviews and Interviews section, so I am working on a round table consisting of myself, Roger Reeves, Natalie Diaz, Jamaal May, Tarfia Faizullah, and moderated by Alan Shapiro. We were all fellows at Breadloaf this summer, and we are all people of color, so we will discuss the shifting center of attention in American Poetry. I’m finishing my PhD at Houston. I am also writing a memoir about masculinity and fatherhood. I become a father at 17, so I’m writing about that experience. It is going to be pretty taxing.

I think HUSTLE challenges our current interpretation of masculinity by placing the speakers of my poems in difficult situations, where they struggle with the necessity to be strong because of environment or societal and community expectations.

David Tomas Martinez‘s work has been published or is forth coming in Poetry Magazine, Oxford American, Forklift; Ohio, Poetry International, Gulf Coast, Drunken Boat, Poetry Daily, Split This Rock, RHINO, Ampersand Review, Caldera Review, Verse Junkies, California Journal of Poetics, Toe Good, and others. DTM has been featured or written about in Poets & Writers, Publishers Weekly, NPR’s All Things Considered, NBC Latino, Buzzfeed, Houstonia Magazine, Houston Art & Culture, Houston Chronicle, San Antonio Express News, Bull City Press, and Border Voices. He is a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Houston’s Creative Writing program, with an emphasis in Poetry. Martinez is also the Reviews and Interviews Editor for Gulf Coast: A Journal of Literature and Fine Arts, and a Breadloaf and CantoMundo Fellow. His debut collection of poetry, Hustle, was released in 2014 by Sarabande Books, which won honorable mention in the Antonio Cisneros Del Moral prize.

Chelsey Clammer has been published in The Rumpus, Essay Daily, and The Nervous Breakdown among many others. Her essay “A Striking Resemblance” received an Honorary Mention for Water~Stone Review’s 2014 Judith Kitchen Award in Nonfiction. Clammer is the Managing Editor and Nonfiction Editor for The Doctor T.J. Eckleburg Review. Her first collection of essays, There Is Nothing Else to See Here, is forthcoming from The Lit Pub in 2015. Her second collection, BodyHome, will be published in Spring 2015 by Hopewell Publications. You can read more of her writing at: www.chelseyclammer.com.

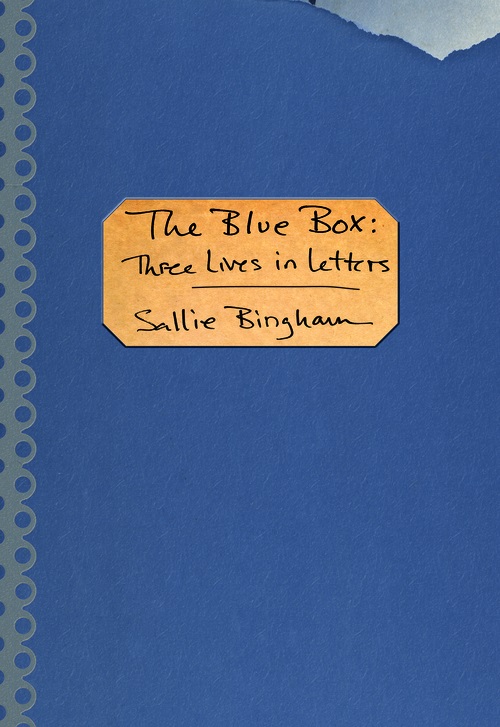

Sallie Bingham published her first novel with Houghton Mifflin in 1961, shortly after graduating from Radcliffe College. Since then she has published four collections of short stories, four novels, the memoir Passion and Prejudice, and several plays, many of which have been produced. Bingham was Book Editor for The Courier-Journal in Louisville, Kentucky and has been a director of the National Book Critics Circle. She is the founder of The Kentucky Foundation for Women and The Sallie Bingham Archive for Women’s Papers and Culture at Duke University.

Sallie Bingham published her first novel with Houghton Mifflin in 1961, shortly after graduating from Radcliffe College. Since then she has published four collections of short stories, four novels, the memoir Passion and Prejudice, and several plays, many of which have been produced. Bingham was Book Editor for The Courier-Journal in Louisville, Kentucky and has been a director of the National Book Critics Circle. She is the founder of The Kentucky Foundation for Women and The Sallie Bingham Archive for Women’s Papers and Culture at Duke University.

Why write a collection of literary essays centered on trees? In Angela Pelster’s debut collection of essays,

Why write a collection of literary essays centered on trees? In Angela Pelster’s debut collection of essays,  Q: Some of the essays in Limber read as stories of other people. How do you approach nonfiction when the narrator is not a central “I.”

Q: Some of the essays in Limber read as stories of other people. How do you approach nonfiction when the narrator is not a central “I.” Q: In her introduction to Trespasses, a memoir consisting of vignettes, Lacy Johnson writes that as she interviewed her family members, she saw how at certain points “the facts got in the way of the truth.” Did you experience anything similar to this as you were writing your collection?

Q: In her introduction to Trespasses, a memoir consisting of vignettes, Lacy Johnson writes that as she interviewed her family members, she saw how at certain points “the facts got in the way of the truth.” Did you experience anything similar to this as you were writing your collection?