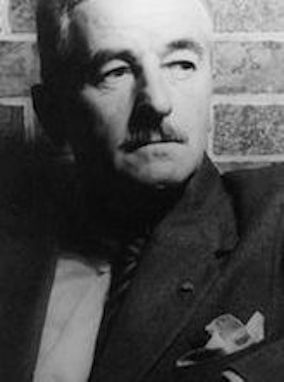

Born: September 25, 1897

Died: July 6, 1962

Little known facts:

William Faulkner was living briefly in New Orleans, Louisiana where he wrote his first novel, Soldiers’ Pay in 1925—after being prompted by Sherwood Anderson to try writing fiction rather than poetry.

Faulkner actually detested the fame from his recognition to the point that his 17-year-old daughter only learned about the Nobel Prize when she was called to the principal’s office.

Much better known facts:

Falkner was his surname until 1924 when, according to one story, a careless typesetter made an error and a misprint appeared on the title page of his first book, a collection of poems. Apparently, the author had no concern about changing it.

Two Pulitzer Prizes were conferred for what most critics consider two of his lesser novels—A Fable (1954) and The Reivers (1962), awarded posthumously.

William Faulkner was an American short story writer, a novelist, and a Nobel Prize laureate from Oxford, Mississippi. He also wrote a play, poetry, essays and screenplays. His most notable works are his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, based on Lafayette County, Mississippi. His characters operate in a social framework that typifies the growth and subsequent decadence of the Deep South and reflect a century and a half of American history, spanning the decades from the American Civil War through the Depression.

Faulkner was born in New Albany, Mississippi, the first of four sons. The family moved and settled in Oxford in north-central Mississippi when he was a child. Though he traveled to Europe and Asia and worked for extended periods of time in Hollywood, Faulkner lived most of his life in that small town in Lafayette County.

While in high school, he began to write poetry, but he dropped out before graduating and went to work in a bank owned by one of his grandfathers. With the entry of the US into the Great War, Faulkner enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force after being rejected from the US Army because he was too short at five feet five inches. He completed basic training in Toronto, but the war ended before he could make his first solo flight. This never interfered with the storyteller relating years later how he had been shot down in France.

After the war, Faulkner studied literature at the University of Mississippi; he wrote poems and drew cartoons for the university’s humor magazine, The Scream. In 1920 Faulkner left Ole Miss without having finished a degree and moved to New York City where he worked as a clerk in a bookstore and lived in Greenwich Village, associating with other writers and artists. When he returned to Oxford, he began work as a postmaster at the University of Mississippi until the university fired him for reading on the job. The submissions to publishers and rejections finally came to an end. In May of 1924, Faulkner’s long-time friend Phil Stone sent a note to the Four Seas Company in Boston asking if they would publish a collection of poems by an unknown writer if the cost of publication were covered. After this first book, The Marble Faun (1924) did not gain success, he left for New Orleans specifically to meet established novelist Sherwood Anderson who took an interest in his work and encouraged him as indicated above to write fiction.

In July 1925, he left New Orleans for Genoa and Paris. During his four months stay in Europe, Faulkner toured the WWI battlefields and also spent ten days hiking in England. After the hiatus, he published Soldier’s Pay (1926), a novel about the return of a soldier, who had been physically and psychologically disabled in WW I followed shortly by Mosquitoes, a satire of Bohemian life in New Orleans.

In 1929 he had his first substantially successful work, The Sound and the Fury, published which earned him some long awaited recognition as a serious writer. In that same year, he married Estelle Oldham Franklin, whom he had courted seriously but unsuccessfully as an undergraduate, after she divorced her first husband. During that year he wrote the first of fifteen novels set in his notional Mississippi. His series deals with racism, class division, and family—as both a life force and a curse—as recurring themes.

The next year he purchased a traditional pillared house in Oxford, which he named Rowan Oak. Many years later, after his passing and the passing of his wife, it was sold to the University of Mississippi and made into a museum.

While working the nightshift at an electrical power station, Faulkner wrote As I Lay Dying (1930)—now considered one of the best English-language novels of the 20th Century.

He dedicated Sanctuary (1931) to Sherwood Anderson “for services rendered,” and, according to the author, it was “deliberately conceived to make money.”

In order to support Estelle and their three children, Faulkner had to work for the next twenty years in Hollywood on several screenplays, from Today We Live (1933) to Land of the Pharaohs (1955). Ironically, the conservative producers considered Faulkner’s stories too daring for film with all their rape, incest, and suicide; and in the publishing world, his Light in August (1932) was initially rejected, but is now also considered one of the best novels in the century.

While engaged in scriptwriting, Faulkner published several other novels: Pylon (1934) and Absalom, Absalom! (1936)—now often considered one of the best novels of the 20th Century and Faulkner’s fourth on that Modern Library list.

By 1945, Faulkner’s novels were out of print and he moved to Hollywood again to write scripts, mostly under contract to director Howard Hawks who had read Faulkner’s 1926 novel Soldier’s Pay when it first appeared.

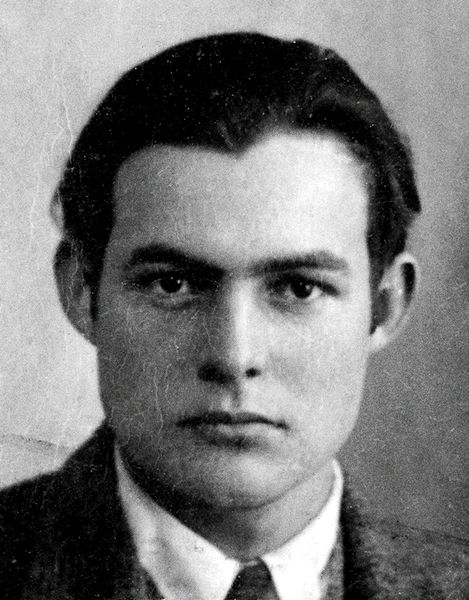

He worked with Hawks on the films To Have and Have Not (1944), based on Ernest Hemingway’s novel, and The Big Sleep (1946), based on Raymond Chandler’s novel. When Hemingway had turned down Howard Hawk’s offer to work with his own book, the director said, “I’ll get Faulkner to do it; he can write better than you can anyway.”

Faulkner had a second period of success beginning with the publication of The Portable Faulkner (1946). However, his physical and mental functioning started to decline, forwarded downslope by his hard drinking and coping with his wife’s drug addiction.

He published Requiem for a Nun in 1951, and A Fable in 1954. The Town (1957) and The Mansion (1959) continued the story of the Snopes family, which he had begun in The Hamlet (1940).

Faulkner was a Writer-in-Residence at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville from February to June 1957 and held that position again in 1958. He suffered serious injuries in a horse-riding accident in 1959, and died from a myocardial infarction on July 6, 1962, at Wright’s Sanatorium in Byhalia, Mississippi. He is buried along with his family in St. Peter’s Cemetery in Oxford.

William Faulkner’s works have been placed within the literary traditions of modernism and the Southern Renaissance. However, he is also cited in the biographies of flagrantly successful magical realists such as Gabriel García Márquez as very significant to their careers because he dared to experiment and depart from convention in modernist work. This view was shared within the literary circle called el grupo de Barranquilla (journalists Gabriel García Márquez, Álvaro Cepeda Samudio, Germán Vargas, and Alfonso Fuenmayor who all became respected novelists or poets) that set about reading the work of Hemingway, Joyce, Woolf, and most importantly, Faulkner.

Perhaps it was Faulkner’s disappointment in the initial rejection of Flags in the Dust that drove him to become less responsive to his publishers and to take on a more experimental style. In any case, Garcia Marquez acknowledges Faulkner and Sophocles as the two most leveraged influences impacting his work. Faulkner amazed García Márquez with his ability to create from his childhood experiences a mythical past, inventing a town and a county in which to frame the actions of his characters. García Márquez found the seeds for his Macondo in Faulkner’s mythical Yoknapatawpha. It is also clear that they admired his use of internal monologue, very long sentences and other techniques considered experimental at the time.

Faulkner’s detailed realism occasionally is punctuated with scenes and moments of very effective magical realism. One such event is found in his short story “The Old People.” The setting is very similar to the much-anthologized “The Bear” where men from several ethnicities and levels of Southern society are all engaged in ritual hunting and prankstering amongst males. During a ritual hunt involving many of the same characters in “The Old People,” there is a coming-of-age ritual for a boy being taught to hunt. The boy is concerned about what seems to him beyond the realm of the real world in his experience. When he relates this to his cousin McCaslin, he finds that his cousin had been brought through this same path by the same man. Their common experience is not easily explained—except to those reared near or in rural cultures, including Native American cultures from which the notion of using natural resources reverently and without waste springs. Specifically, a huge buck that appeared and stood unafraid before the boy and the Native American Sam Feathers soon after the boy had taken his first buck and had been marked by Sam with the blood of the smaller buck as having been worthy of taking a life and having taken that life carefully and respectfully. This kind of blurring of “realities” and the prompting of alternative perceptions is Faulkner’s brand of magic realism.

Faulkner was regarded as a relatively obscure writer until he received the 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature. Then nearly a half century later in 1998, the Modern Library ranked his 1929 novel The Sound and the Fury sixth on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. Absalom, Absalom! is often found on these lists and is usually cited as his masterpiece over The Sound and the Fury when discussing his body of work and not a comparative list.

Faulkner donated part of the Nobel Prize to establish a fund to support what became the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, and donated another part to establish a scholarship fund to educate African-American teachers at Rust College in Holly Springs, Mississippi.

A FEW OF WILLIAM FAULKNER’S QUOTES

“The writer’s only responsibility is to his art. He will be completely ruthless if he is a good one. He has a dream. It anguishes him so much he must get rid of it. He has no peace until then. Everything goes by the board: honor, pride, decency, security, happiness, all, to get the book written. If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the “Ode on a Grecian Urn” is worth any number of old ladies.” (Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews, 1959)

“I’m a failed poet. Maybe every novelist wants to write poetry first, finds he can’t, and then tries the short story, which is the most demanding form after poetry. And, failing at that, only then does he take up novel writing.”

“Hemingway has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary.”

A FEW QUOTES ABOUT WILLIAM FAULKNER

The New York Times cited his critics in his obituary: “Mr. Faulkner’s writings showed an obsession with murder, rape, incest, suicide, greed and general depravity that did not exist anywhere but in the author’s mind”. (July 7, 1962)

Nobel writer J.M. Coetzee defined Faulkner not only as “the most radical innovator in the annals of American fiction,” but “a writer to whom the avant-garde of Europe and Latin America would go to school.” (The New York Review of Books, April 7, 2005)

WILLIAM FAULKNER’S NOTABLE WORK

The Sound and the Fury (1929), Sanctuary (1931), Light in August (1932), Absalom, Absalom! (1936), The Hamlet (1940), Intruder In the Dust (1948), Requiem For A Nun (1951, Collected Stories (1951) National Book Award, A Fable (1954) National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize, The Town (1957), The Mansion (1959), and The Reivers (1962) Pulitzer Prize (posthumously.)

WILLIAM FAULKNER’S AWARDS

Nobel Prize in Literature (1949)

France’s Chevalier de la Legion d’honneur (1951)

National Book Award for Fiction (1951, 1955)

Pulitzer Prize for Fiction (1954, 1962)

American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal for Fiction (1962)

SOURCES

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/themes/literature/espmark/index.html

Eric R. Kandel. The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain From Vienna 1900 to the Present. New York: Random House, 2012.

The New York Review of Books, July 7, 1962

The New York Review of Books, April 7, 2005

Horst Frenz (ed.) Nobel Lectures, Literature 1901-1967, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1969.

Petri Liukkonen. “On William Faulkner,” from Pegasos Author’s Calendar.

Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews, 1959.

Richard Perkins is a regular contributor to The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review and a graduate of The Johns Hopkins University MA in Writing Program. He is writing an historical novel and revising a collection of connected stories.

ERNEST MILLER “PAPA” HEMINGWAY

ERNEST MILLER “PAPA” HEMINGWAY