The Gift

My racial biases developed in layers with attitudes and perceptions accreting from my earliest years. My parents’ behavior—their words and body language—when encountering someone different in color or features or accent, swayed me in a patronizing direction. Playmates, teachers, relatives, and other adults, through their conduct, instilled an intolerant bent in me. I held disdainful assumptions as truth. Similarity was attractive; I viewed the dissimilarities in the thick lips, broad noses, and kinked hair of African Americans as unattractive. Many spoke with an accent or in a dialect I regarded as signs of being unschooled. My desire to be esteemed by my kind bolstered my distorted sentiments. My posture toward blacks was condescending and smug at best, unreasonable and hateful at worst. A product of surroundings and disposition, I was not unique.

My biases were formed in a setting, the rural Midwest, in which I had little exposure to African Americans. I remember one or two trips, with my mom and dad, to a black neighborhood in a small town. We visited an older African American lady who had looked after my mother and her preadolescent siblings, and who lived in a tiny abode with tar paper-like siding. My parents brought her the leftovers from a hog they’d slaughtered—the head and feet.

I also recollect a handful of outings to Kansas City, riding with my family through black business and residential areas on our way to the zoo or some other destination. We stared through the car windows at the bleak little houses and the alien faces; when picnicking at Swope Park or visiting its zoo, we watched but didn’t interact with families in every way like ours, except for the color of their skin.

The Doll Test

In the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education, plaintiffs made a compelling argument that segregation had harmful effects on black children. In their doll test, psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark, using black and white dolls, asked African American preschool and elementary school children from the South and North to choose the doll they preferred. Two-thirds selected the white doll, and a majority indicated the black doll “looks bad.” In another study, they asked the test subjects to “color line drawings of a child” with a hue closest to their own skin. The youngsters often used a shade lighter than their complexion, with some displaying “emotional conflict” when asked for a color preference. The Clarks found that black children, on the whole, “viewed white as good and pretty, but black as bad and ugly.” Their conclusion was “the Negro child, by the age of five is aware of the fact that to be colored in contemporary American society is a mark of inferior status. A child accepts as early as six, seven or eight the negative stereotypes about his own group.” These findings “illustrated the effect of prejudice and discrimination on personality development,” allowing the plaintiffs in the Brown case “to show that segregated schools were inherently unequal, and therefore unconstitutional.”

Freedom of Choice, Not Full-Scale Desegregation

“It was a pamphlet that was sent out from the school district to all parents,” Hull Franklin recalled. During the 1960s, households throughout the South received information about the freedom-of-choice plans, giving students and their families the opportunity to choose their schools—without regard to race. Another pupil from that era, Ruth Carter, chose to go to the white school because she thought she’d get a better education, and for another reason: “Everything in the city, everywhere you go it was signs ‘White Only’…And I thought this would be the first step towards change…by us going to the all white school.”

In response to the Supreme Court’s striking down of mandated school segregation in the Brown ruling, Southern states cleaned up their statutes and constitutions by removing education clauses, and did nothing else. But with the threat of losing federal financial assistance, school boards began implementing freedom-of-choice plans instead of full-scale desegregation.

Despite the flaws in freedom-of-choice plans, a small cohort of black children and adolescents chose to attend white schools. They entered a crucible in which their courage and determination were on trial. Forty to fifty years later, some of these pioneers depicted their efforts in oral histories collected by the College of Charleston. “They wouldn’t sit with us in the cafeteria, they…called us names, they’d throw spitballs, they’d throw chalk. You’d walk down the hall they’d jump to the other side of the hall. You’d sit at a table in the library [and] you’d be the only one at the table…and then they got so bad at the cafeteria, not only did they not want to sit at the same table, they didn’t want to sit on the same isle,” Gloria Carter remembered. At home, “Each child would share and talk about their day at school,” her sister Ruth noted. “There was no pleasant day.”

“I became paranoid about lunchtime,” recounted Carlton Wilson. “I would want to get to the cafeteria early so I could get me a table…if all of the seats were taken, or if everybody was sitting at every table, I wouldn’t have anywhere to go, because…when I went to the table people would get up and leave…So I would automatically go to an empty table so no one would sit with me. And the other part of the day when I became very nervous was…when school ended, going to the bus, because the fear was that you would get to the bus and not have a seat, because you couldn’t sit beside a white person because you didn’t want to feel that…if you couldn’t get there and have a seat, then you would have to stand up.”

“We were either not there or we were treated badly to say the least,” said Lucy Frinks. “We were taunted and, from the other white students, what would be considered nice treatment would be that someone smiled at you. Certainly nobody spoke to you about anything. It was like you were invisible. Nobody talked to you. Nobody touched you. Rather than touch you people would move to the side. It was like we were pariah.”

Millicent Brown, one of two African American students in a school of eight hundred, described the isolation: “[W]e didn’t have lunch together. We didn’t have any classes together. And I always knew [the other black student] was going through it alone and I was going through it alone.” Besides the white kids, African American pupils had to deal with the adults—the teachers and administrators.

“The whole atmosphere is, ‘You’re here and we have to do our job.’ Pretty much that’s what it felt like,” Emma Harvin declared, “[they had] no choice” but to teach the black children. Ruth Carter told of how her sister Pearl was treated by one teacher: “[S]he would move the [white] child that’s sitting next to her each week. That child wouldn’t have to sit there all the time. She would rotate the kids around Pearl because she didn’t want to punish [them]…when she’d work with Pearl, she’d hold her nose when she’d stand over her. She was mean to her.”

Lucy Frinks gave other examples of how authority was administered: “There were rules in the student handbook where you could not carry [an Afro] pick.” She adds that black pupils couldn’t sing “Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud” without being “expelled…but we could have ‘Dixie’ played at the pep-rally…You could wear confederate flags and what not, but you couldn’t wear a t-shirt with Angela Davis on it.”

For Millicent Brown, each day was humiliating: “[A]fter a year or so [white] people did sit with me and talk. They accepted some things, but they never wanted to be seen walking with [me] coming out of the assembly.” She said, “[A]s soon as you started thinking folks were kind of cool with you then something would happen and you’d be reminded that, ‘no, [they’re] not really.’”

Bigotry Accretes

I assumed black people chose to be separate until a chance occurrence at a hall of justice. I was ten years old and with my mother at the courthouse in neighboring Clay County. In keeping with the pro-Southern leanings of western Missouri, the courthouse had separate restrooms for whites and blacks. Seeing the “whites only” sign at the entry to the ladies’ room, my mother became angry, though she downplayed it by saying, “I’d like to see them try to stop someone who needed to use it from going into that restroom.” I was disturbed by her reaction; it was the earliest moment I recall grappling with the notion that public decrees can hurt individuals.

At the age of fifteen, I along with half a dozen kids from our parish attended a mini retreat of teenagers from four Catholic congregations. After introductions, the facilitator asked for volunteers to read a biblical verse to the gathering. One of our faction—a slender girl with lank, light-brown hair, a year older than me, and popular with the others in our clutch—volunteered. Our suburban group comprised white members except for one guy from India, but participants in the other groups, all from the city, were black. Four presentations were given by two girls and two boys. Three of the performances were embarrassing: Each of the black readers stumbled over the words—words we white pupils came across, in school or our middle-class settings, on a routine basis. The white girl read her verse without hesitation, making no errors. When the readings concluded, the audience stared at the floor as if meditating on the spoken messages. I sensed unease in the room and guessed others were reacting as I was: These high school students couldn’t read at a fourth-grade level.

Compared to Midwestern norms of the time, I lived in an “enlightened” household. Our mother told us not to call blacks the common epithet many in our family and most of our neighbors used; they are Negroes or colored. We should ignore denigrating remarks; although, she said they ate inedible food such as pigs’ feet and hog jowls, and some had a disagreeable odor. And we should not be mean to them.

Despite what I was taught, I accepted the offensive words and malevolent attitudes of family and friends lest they shun me. I rationalized there were grounds for looking down on people of color. In my childhood, my limited acquaintance with African Americans led me to think there was an innate difference between us. Even though I knew abusing them was wrong, I felt they were inferior. No one—not parents, not teachers, not priests nor nuns—made a contrary argument. Never a loud bigot, I was a complacent member of the herd, a quiet and insidious enabler of loud bigots.

Follow-Up Doll Test

Child psychologist Margaret Beale Spencer redid the Clarks’s doll test, but unlike the first study, she included white children. There were two age groups, four to five and nine to ten, who were asked a series of questions. The children responded to the questions by pointing to one of five cartoon pictures displaying variations in skin color from light to dark. Additional queries about a color bar with light to dark skin shades were put to the older children. As a group, the white children associated “the color of their own skin with positive attributes and darker skin with negative attributes.” Although less pronounced, the African American children also “had some bias toward whiteness.” In a surprising result, perceptions of race didn’t shift with age—the findings were similar for both the five-year-old and ten-year-old children. In Spencer’s words, “We are still living in a society where dark things are devalued and white things are valued.” Her study was done over six decades after the Clarks’s research.

Cultural Impact on Students

Several of the freedom-of-choice interviewees remembered how they were treated by peers remaining at the black schools. Theodore Adams recalled the disrespect he received from those who felt: “[Y]ou want to be white, you think you [are] better than we are, we don’t want to associate with you.” A parent, Arlonial DeLaine Bradford, whose children were in the first group to integrate the classrooms in a small South Carolina town, described the response she received in the community: “[T]he Black folk said that I thought that my children were white, and they were better than the other children, and that there were no teachers in the Black schools fit to teach them, and so they gave me a rough way about that.”

Erstwhile classmates refused to sit by the desegregation firsts during basketball and football games played at the black institutions. “[O]ne would think by doing what we did that maybe we would have been lifted up in our community,” Theodore Adams exclaimed, “but we weren’t. As a matter of fact, we lost friends. Some of the young people that we grew up with didn’t hang out with us anymore. It was like we were caught in the middle of a no-man’s-land…we were hated by the students we were going to school with and not trusted by a lot of the ones that we would’ve been going to school with at the Black high school.” He went on to say he attended some events in the community and at the black school, but they had to be chaperoned—no backyard parties—because “when you fight all day, you don’t want to have to fight all night too.”

Some of these pioneers, who were “marginalized in their communities” and ostracized in the schools, became quiet, “withdrawn.” Decades later, Lucy Frinks lamented, “It’s like this piece of us that nobody speaks about.” She and her cousins were among the ten black students who integrated a rural South Carolina school system. “[W]e haven’t talked about it and I know it had a very profound impact on my life. And I’m sure on the lives of my cousins.” After giving an account of the dread, anger, and sadness she felt during the desegregation effort, Ruth Carter said it’s a topic she doesn’t bring up with young people, “I don’t talk to them about my life as a child and growing up in Mississippi…I don’t even talk to my own kids about it.”

Three years of the stressful environment sickened Millicent Brown: “[T]hey thought I had a heart condition because I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t walk five feet without just being totally out of breath…we found out that I had a nervous condition.” Besides the abuse from whites, she adds, “I became afraid…of what it is that Black people think about me in a way that I wasn’t conscious of before…I really believe that discomfort stings today.”

But another desegregation first differed in his perspective. “You hurt. Let me tell you about the hurt. You hurt in the moment that [it] was happening. You hurt you feel as a child, but one thing about being an adult,” Hull Franklin averred, “you grow up, you get over it. Let it pass. It passes…I cannot hold that against anyone because it’s not about them. It’s about me now making myself better…[I] have a positive attitude on life.”

“All White People Are Racists”

While African American pupils integrating schools were haunted by futility, Martin Luther King, Jr., offered hope. He spoke of fulfilling the dream for equality: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Though optimistic, he asserted success will require courage and persistence. With hard work by both races, he believed justice would prevail. “We will overcome.”

One race has been negligent. “[T]he statement ‘all white people are racist’ doesn’t make me angry. It makes me sad, because I believe it’s probably true,” said Katherine Craig, a white human rights lawyer. “[I]f you grow up in a racist society,” she maintained “through no fault of your own, some of that racism is bound to stick subconsciously. It’s…[a] conspiracy in which we are all complicit, unless we fight it.”

Blemishes Remain

I left home at age twenty. While my views had been evolving for several years, they solidified when, in my new surroundings, I encountered people who held that racial disparities were anathema to a healthy society. Many of my colleagues were black, and on occasion, we socialized. I began to voice a conviction that racism was unjust. I deemed my deeds mirrored how a good person behaved and my words echoed what a good person said. On the surface, I was spotless; beneath it, I was blemished.

In my sixties, as a volunteer advocate for residents of long-term care facilities such as nursing homes, I’ve had to fend off more than one woman (two, to be precise) attempting to entice me into her bed. Their profile: dementia or mental illness, between sixty and seventy, thin, and aggressive. One woman, with an emaciated look and pale white skin, intent on more than talking, gave me her phone number and asked for mine (she got the program’s office number). While I stayed a couple of feet away from her, I was flattered. On another occasion, a woman whose shoulders had a slight stoop, and whose skin was a coffee-with-cream hue, said on seeing me, “My, you’re fine looking,” and reached out to me. I stepped back beyond the range of her outstretched hand, a reaction impelled by distaste.

How do I continue to fight my racism? My attitudes toward those different from me are hard to control, yet I can resolve to manage them. I can choose to denounce racist comments by acquaintances; I can choose to listen to the stories of persons oppressed in our society and to learn more about them; and I can choose to offer assistance, meager though it might be. Over time, such choices will reshape my nature.

I have a friend who was among the first African Americans to integrate a high school in the South. Five decades after battling iniquity—the merciless animosity scarring her childhood and adolescence—she wonders what benefits were attained by the fight for an interracial education. While public facilities, including learning institutions, dropped “whites only” restrictions, we failed to dull the sharp edges of racism. Was it all for naught? Did we miss an opportunity to bend the arc of the moral universe? If we give an affirmative answer to these questions, we are disregarding the struggle these pioneers waged. We would be making a mistake.

Treated as untouchables no white person would sit with or talk to, spit on, kicked, ignored by uncaring educators, and snubbed in their own neighborhoods, my friend and others held their tempers and their tears, ignored the epithets, and concentrated on their studies. They offered us a gift: In their dignity and integrity, their sacrifice and courage, they exemplified what we are capable of. It’s an offering we can accept or reject.

##

Sources:

Interviews are part of the oral history collection of the Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: http://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/?f%5Bcollection_titleInfo_title_facet%5D%5B%5D=Somebody+Had+To+Do+It

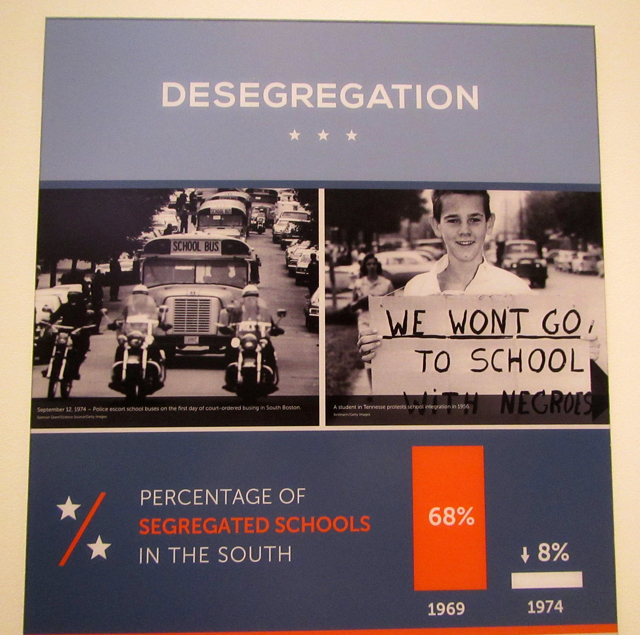

Photo at the top of the page: “Southern Desegregation (0045)” by Ron of the Desert is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0