Teenagers are a demographic—they’re the “younger set” or the awkward space between the ages of 13 and 18. They’re “young adults” and “adolescents.” There’s no question about the insularity of their interests or the depth of their understanding. The publishing industry’s got them figured out. Take a look at the lion’s share of “teen” literature that’s rolling out these days, and you’ll get an eyeful of clichéd romances, cliquey chick lit, and the like.

Because teens aren’t anything more than that. Right?

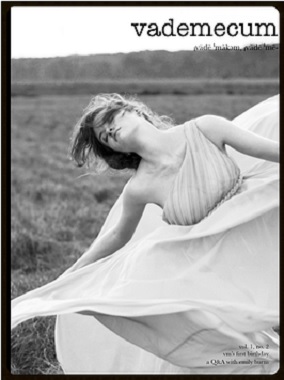

Apologies for the vitriol. I’ll avoid generalization and say that the above doesn’t apply to all teen literature. It does, unfortunately, apply to a great deal of the material that’s on my public library’s “teen literature” shelves. In an earlier column, I wrote about teenagers as the real avant-garde of literature; here, I’ll elaborate some more, with some examples from Vademecum’s pages to boot.

I believe that teen literature—poetry, prose, and everything in between—deserves a platform of its own. If it sounds horribly ironic to shout down teen lit in one paragraph, then hold it up to the light in the next, well—it is. But that’s only because the definition of teen literature, as it currently stands, is in sore need of an update.

Teen writers need a platform of their own. Just as the New Yorker (every writer’s wet dream, really) is a haven for literary luminaries, teen lit should highlight the creative output of a group—a group with experiences shared and varied. And this nebulous title shouldn’t become synonymous with bad writing when teen writing can be as good as (indeed, sometimes better than) the output of “professional” adult writers.

The editors of Vademecum Magazine receive stellar submissions of poetry, prose, and photography on a daily basis. And, while we unfortunately can’t publish every piece that lands in our inbox, we do pride ourselves on communicating with submitters to polish and present each piece for publication. That being said, the raw talent we’re privileged enough to work with is alternately outrageous/beautifully strange/innovative/suggestive of other worlds and other planes of existence.

Take, for instance, this short piece from volume 1, no. 3 by contributor DeMauray McKiever:

Foreign Language

“When I spell grey with an e,

it makes me think of the smooth round rocks

you can only find on cold, foggy beaches

in the early morning.

In an early morning dense with

sand and a wet breeze.

An early morning when only

one bird sings, and then sleeps.

An early morning when

the tide and the people are low.”

Post-read, my first thought was that there was something tremendously organic about the talent behind “Foreign Language.” Something utterly unfeigned, unassuming (“An early morning when / the tide and the people are low”—swoon-worthy). There’s a difference between childish and innocent, and this piece was the latter—breathtakingly so.

But I also attempted to fiddle with a few of the poem’s opening lines, only to find that my edits worked to the detriment of tone and form. I read the second line (“it makes me think…”) and worried about the grammatical accuracy of the sentence’s beginning. I’d recognized the opening—that particular opening, “it makes me think…”—in the speech of young children. Here, it could fit, I thought. After some back-and-forth, however, I still wasn’t sure. I suggested an edit to “I think of the smooth round rocks…”

Thank god for the word of Vademecum’s genius poetry editors, Ameerah Arjanee and Greta Unger. Ameerah and Greta suggested that we retain the poem in its original form—a rare recommendation from the magazine, where most accepted pieces are in some way edited before hitting the presses.

In retrospect, I wouldn’t have had “Foreign Language” any other way. Where the original line connoted a kind of wide-eyed wonder, my edit drained this from the line and made it stuffy. The curious observer of the world was sadly transformed into something infinitely less interesting: a whole lot of hand waving philosophizing (“I think of etc, etc, etc”) in place of original, lucid observation.

So my thanks to DeMauray, Ameerah, and Greta for a crisply beautiful short poem and a lesson in editorial savvy.

It’s this kind of realization that speaks to my earlier tirade regarding the divide between teen literature and the adult publishing world. In the context of teen literature, at least, teen writers receive an objective overview of their own work. The divide wouldn’t be necessary, perhaps, if teen writers were provided with the same kind of objectivity afforded to established writers by established publications.

I could argue that younger writers bring a young person’s perspective to their pieces; they’re also capable of writing like any number of professional poets. They’re originators of style and content, initiators of entire movements, and wellsprings for new ideas. But, until they’re lent the degree of artistic credo that older writers enjoy by dint of age, they also deserve their own space.

Madelyne Xiao is a senior at Urbana High School in Frederick, Maryland. She’s been published in Polyphony HS, the Blue Pencil Online, Stone Soup Magazine, and Cicada Magazine. She loves words. Vademecum is her baby.