Eric Carle, Eric Carle, I hope you can see:

This daddy (that’s me) reading stories to three.

Eric Carle, Eric Carle, your words that I’m reading,

they’re the last my kids hear each night before dreaming.

Eric Carle, Eric Carle, please don’t think me a stalker,

even though I know your stories by heart, as do my sons and my daughter.

Eric Carle, Eric Carle, I must confess

I’m bored with your stories (thank goodness that’s off my chest).

They’re fun and they’re cute and my kids love them so much,

but I’ve been reading them for ten years; enough is enough!

With a sudden hankering to read something new,

I Googled your name as my kids snored and snoozed

Eric Carle, Eric Carle, my goal was simple at its core:

to learn about your life, to learn about your lore.

In 1935, your family moved when you were just six,

to Germany so mommy could have her motherland fix.

Soon Hitler came calling and drafted your dad,

forcing him into the Reich; oh, how very sad.

Your father was captured near the end of the war,

and the Soviets locked him away to rot to his core.

Eric Carle, Eric Carle, how traumatic that must’ve been,

not just for your father, but for you and your kin.

Years later, when the Russians returned him home,

he was mentally devastated, all skin, all bones.

But before we go further, let us not forget,

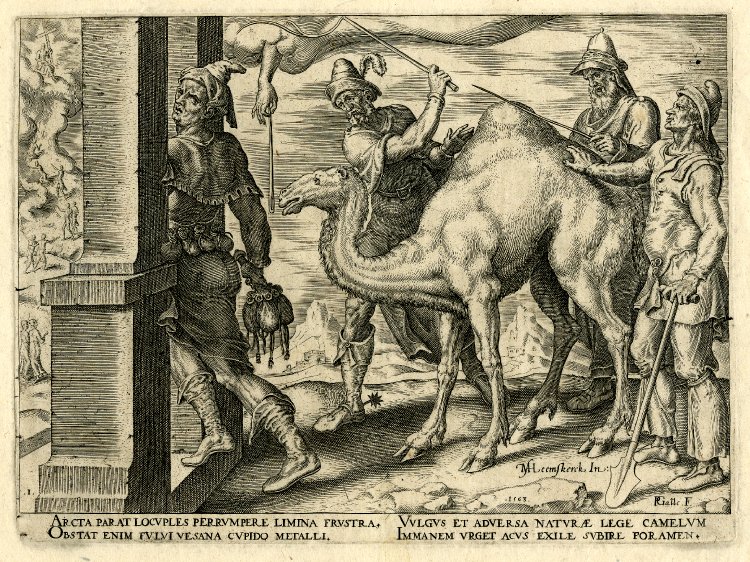

the Deustche Armee drafted you, too, to serve as their pet.

Eric Carle, Eric Carle, you had the world’s worst chore:

digging trenches for the Germans during the second world war.

You were barely a teen then but saw people die?

That doesn’t show up in your books, and I think I know why.

I mean:

Dead body, dead body, why do you smell?

Perhaps hungry caterpillars shouldn’t discuss heaven and hell.

I have more to report, but first I have to admit

these rhymes are getting tiresome, so I’m going to stop for a bit.

Eric, here’s the simple truth: I didn’t know a thing about you until very recently. I’ve read all your stories, taken my children to plays based on your books, rhymed your words in the rhythms you demanded, and did so without knowing if you’re even still alive (good news, Eric: you are!). Here’s what else I learned: you once broke two vertebrae in your back after falling from a tree; you rarely visit schools in person these days; you once envisioned careers in forestry and the food industry at different points in your life; and years after Germany forced you into their war efforts, America did the same, drafting you into the Korean War and assigning you to a post back in Deutschland. You previously worked for the New York Times and have even had sex at least twice in your life (and I’m sure your son and daughter are thankful for this).

I’m glad I learned these things, Eric, because I owed it to my children to know something about the man whose ideas are present in our home more frequently than extended family. My children know your very quiet cricket and mixed-up chameleon better than they know any of their grandmothers’ maiden names. They can recall everything that your polar bears can hear, everything your brown bears can see, but struggle understanding which cousin belongs to which side of our family. This is my fault, of course: I choose to tell them your stories, not my own or our family’s. I’ve often wondered why this is. There’s plenty of love and generosity and selflessness in our history, much photographic and anecdotal evidence to show that we support the characteristics you trumpet in your books. There are also many stories planted deep in the soil of the seven deadly sins, PG-13 and rated R tales we keep hidden behind walls of introversion and redirection.

So why don’t I tell my children these stories, both the happy endings and the sour? I never had an answer for that question until I read through your biography and learned that you don’t like to reflect upon your father’s imprisonment or your time digging those trenches, that you avoid thinking about the three people you saw killed that first night with a shovel in your hand, that your wife thinks you have PTSD because of all this trauma.

Eric Carle, Eric Carle, I read this and knew

that some stories, especially those so close to us, are harder to tell when true.

##

Photo at the top of the page is by d squared and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.