“Poe’s jealousy of other writers amounted to a mania.”

Frederick Saunders, biographer of Edgar Allan Poe

Dueling preceding boxing, headbutting, and backstabbing as the gentleman’s way of resolving literary and extra-literary disputes.

After publishing Pleasures and Days, Marcel Proust challenged critic Jean Lorrain to a duel for a review depicting him as “one of those pretty boys who’ve managed to get themselves pregnant by literature.”[1] He had taken critic Robert de Montesquiou’s broadside – “a mixture of litanies and sperm” – in stride, even finding it flattering. But Lorrain’s was below the belt. The two gay asthmatics managed to rise before dawn and find a free meadow. But both shot over each other’s head, returning home for hot compresses and cognac. Proust staged several other such duels, health permitting.[2]

Then came the Turgenev-Tolstoy showdown that didn’t happen, a bitter disappointment for Dostoyevsky. It all started when Ivan badmouthed the motherland in Smoke, and Fyodor suggested the novel be “burned by the public executioner.” Ivan in turn called the newly patriotic gulag con a “madman” and a “petty, dirty gossip”; Fyodor then parodied him in The Devils as “the most written-out of all written-out authors”; whereupon Ivan called him “the Russian Marquis de Sade.”[3]

Tolstoy found all this deeply disturbing since he liked both the fussy dilettante and the excitable epileptic. He’d even called The House of the Dead, “the finest work in all of Russian literature.” In turn, Dostoyevsky heaped praise on Tolstoy (though, in private, he found his masterpiece, Anna Karenina, “rather tedious”). So, diplomatically, Tolstoy was between a rock and a hard place.

The scales were tipped one day when Tolstoy scolded Turgenev about his poor treatment of his daughter born to his mother’s slave, “If she were your legitimate daughter, you would educate her differently.” Ivan threatened to slap Leo’s face. Instead Leo suggested a duel. But soon, conscience getting the best of him, Leo apologized to Ivan and called the whole thing off so as not to interrupt his work on War and Peace.

At about the time Dostoyevsky returned from Siberia and got into it with Turgenev, he was thrilled to discover Baudelaire’s translation of Edgar Allan Poe, no less excitable and choleric than himself. Inside the great American bete noir raged a perfect storm of megalomania, touchiness, frustration, and rage even greater than that of his hypercompetitive successors, Hemingway and Faulkner.

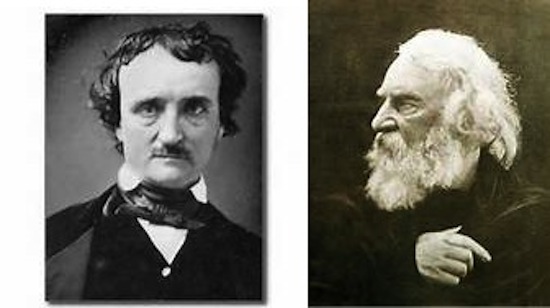

The poet had many unwilling sparring partners. His early favorite was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Longfellow had done nothing in particular to piss off Poe, other than outselling him, being an esteemed professor, and having a rich wife.

Initially, the young firebrand had called Longfellow a genius and begged him for an endorsement of his work so “my fortune will be made.” When Longfellow declined, Poe dismissed him as “the GREAT MOGOL [his caps] of the Imitators” and a plagiarist.[4]

Henry played rope-a-dope with Edgar, stoically taking his most devastating shots, and saying only, “Life is too precious to be wasted in street brawls.”

Beside himself, Poe threw haymakers at his rival’s Poems on Slavery, saying they were written “for the especial use of those negrophilic old ladies of the north, who form so large a part of Mr. LONGFELLOW’s friends.”

Returning to his corner at the bell, the father of Horror cooled down with the sponge. He then counted himself one of his opponent’s “warmest and most steadfast admirers,” and regarded him as “the principle American poet.” Ignoring the olive branch, Henry still stubbornly refused to endorse the ambitious upstart’s work.

Poe soon traveled to Boston to deliver his lecture “On Reason.” Receiving a chilly reception from unreasonable Bostonians, he called everyone in the audience a plagiarist. He then carriaged across town to the Lyceum to read “The Raven,” only to realize, en route, that he’d forgotten to pack his popular poem. So he recited it by heart with some stammering and hyperventilation. As audience members walked out, he hectored the stage, cackling that he had “demolished” the Walden “Frogpondians.”

Back in New York, Poe courted patronesses while his wife/cousin, Sissy, was in the last stages of TB at home. He boasted that one, Mrs. Ellet, was sending him love letters. She charged him with libel and enlisted gentlemen to protect her honor. The penniless poet hurried to his colleague, T.D. English, asking to borrow his pistol.

T.D. had recently published a parody of “The Raven.” Poe felt that the least he could do, by way of making amends, was to lend him a piece to protect himself against Mrs. Ellet’s champions. But English insulted him again, suggesting that he apologize to the widow. Poe had recently finished “The Cask of the Amontillado” in which his hero, Montressor, making good on his motto — “Nemo me impune lasessit” (No one insults me with impunity) – buried his rival, Fortunado, alive.

Instead of walling up T.D. in a wine cellar, Edgar boasted that he “gave English a flogging which he will remember to the day of his death… [and] had to be dragged from his prostrate, rascally carcass.”

English had a different take on the bout. He said he flattened the bard’s nose with a signet ring punch, sending him “to bed from the effect of fright and the blows he received from me.”

Poe wrote “Literati,” a caricature of the work and physical peculiarities of English and his allies. After its publication, the author announced his plans for a sequel, “American Parnassus,” which would discredit the entire American literary population. According to biographer, Kenneth Silverman, he vowed that the title would be “a culmination of his work as a critic, aesthetician, and tastemaker.”

Rebutting “Literati” in the New York Evening Mirror, magazine publisher, Charles Briggs, described his former editor and book critic as a self-confessed forger and a loan cheat. Adding insult to injury, Briggs described Poe as: “5 feet 1…. His tongue too large for his mouth… his head… of balloonish appearance.”

The poet sued the Mirror for libel, insisting that his character was unimpeachable. Furthermore, he described himself as 5 feet 8, English a dwarf by comparison, and the Mirror’s owner, Hiram Fuller, “a fat sheep in reverie.”

English scorned his rival’s “exhibition of impotent malice,” adding: “The kennels of Philadelphia streets… have frequently had the pleasure of his acquaintance.”

Edgar launched a flurry of body blows, calling T.D. out for his “filthy lips,” his “wallowing in hog-puddles” and his resemblance to “the best-looking but most principled of Mr. Barnum’s baboons.”

Two years later, Poe was in a Baltimore ER watching, according to his physician, Dr. Moran, “spectral and imaginary objects on the walls.” In a brief moment of coherence, he told Moran “the best thing my best friend could do would be to blow out my brains with a pistol.”

The next day he muttered, “Lord help my poor soul” and expired. Some say of drink, others “congestion of the brain,” others of rabies.

[1] Edmund White, Marcel Proust (Fides, 2002)

[2] William C. Carter, Marcel Proust: A Life (Yale University Press, 2000)

[3] Myrick Land, The Fine Art Of Literary Mayhem (New York: Holt, Rinehart, Winston, 1963)

[4] Kenneth Silverman, Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance (New York: HarperCollins, 1991)

David Comfort has published three popular nonfiction titles from Simon & Schuster, and a fourth from Citadel/ Kensington. “Bards Behaving Badly” is excerpted from his latest trade title, An Insider’s Guide to Publishing, released by Writers Digest Books in December, 2013. Comfort is a Pushcart Fiction Prize nominee, and a finalist for the Faulkner Award, Chicago Tribune Nelson Algren, America’s Best, Narrative, Glimmer Train, Red Hen, Helicon Nine, and Heekin Graywolf Fellowship. His current short fiction appears in The Evergreen Review, Cortland Review, The Morning News, Scholars & Rogues, Inkwell, and Eclectica Magazine.

Mailer disdained Faulkner for his “mean small Southern streak” and for never saying anything “interesting,” but shared his supreme vanity and ambition.

Mailer disdained Faulkner for his “mean small Southern streak” and for never saying anything “interesting,” but shared his supreme vanity and ambition.