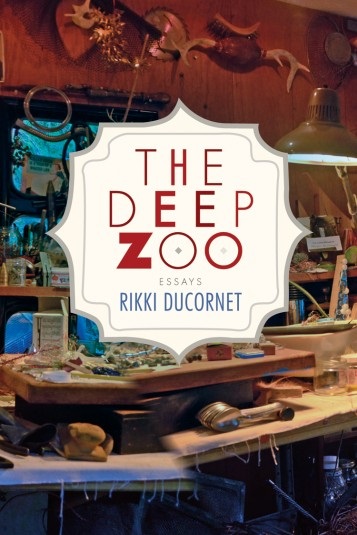

In her new collection of essays, The Deep Zoo, artist and writer Rikki Ducornet looks at where imagination, violence, dreams, and fairy tales represent the deep zoo at the core of humanity. Here, Ducornet discusses further the ways in which art and the written intersect in our lives and relations with one another, where the creative impulse lives within all of us, and ultimately, as Ducornet describes here, how “We come into the world wired to make art. The creative imagination is what drives us, nourishes us, gives us the taste and the capacity for life.”

![]()

Chelsey Clammer: In the title piece in your collection of essays, The Deep Zoo, you write, “The texts we write are not visible until they are written.” At the end of this piece you state, “Writing is a reading of the self and of the world.” I’m curious, then, what it is you think our writing means before we actually sit down to write. In other words, what do you think about how we see ourselves (“read” ourselves) and the world before we are able to get our thoughts outside of our heads? Can we identify with them, or are our identities and conception of self not fully developed until we are able to write about them?”

Rikki Ducornet: I began as a painter and a printmaker. Writing took hold unexpectedly; it would surface in my paintings as lines of poetry. And then it began to pounce. It was very like being stalked! Stalked by a wild thing from the woods! And it was a wild thing from the woods! Because it was the subconscious that was stalking and pouncing. The first short story I wrote came to me in a bathtub. It was called “Aunt Rose and Uncle Friedle.” Sopping wet I ran for a pen and wrote it down. The stalker was imperious you see! I sent that story to my mother who was dying of cancer in another country and her reaction was: “Some nightmares are best kept to oneself.” But I knew better than to keep the nightmares to myself. And I also knew that my mother was impervious to black humor.

Later I came to see that all that stalking and pouncing wanted a home for itself, wanted a book. And I wrote that first book, The Butcher’s Tales, under the influence of an imperious need to begin to grapple with the world and myself within it. The pouncing had all to do with a longing for moral understanding, a visceral need to confront abusive authority in its many forms and to fully engage the beautiful. So, yes, writing became a way to actually see, on the page, what the questions were that needed my attention. And the fact of seeing my inquiry written down revealed to me my own inadequacy, as well as my own fearlessness and even capacity for transcendence. The stories often made me catch my breath because they were revealing me to myself just as they were leading me deeper into the world of ideas. And they made me laugh. They were subversive and vivifying! In other words, my own experience of being a person in the world has been extended dramatically by the process of writing. I don’t think writing is the only way, but I do think it is a real gift. And the marvelous paradox is that when we are writing from an authentic place that is uniquely ours, others respond. Because that place is the holding ground of the breath of Eros, the place of essential reveries. It is uniquely human. The deep zoo has deep roots within all of us.

CC: I have another question about the essay that opens your collection entitled “The Deep Zoo,” because I’m absolutely in love with this essay and could probably talk about it forever. Since we don’t have forever, I’ll have to settle on one more question. You present a great concept towards the end of the essay in which you say, “If a book is a place to think, it is a pragmatic place, a place of experiment.” Thinking about public and private spheres, where do you think the best place is to experiment with you thoughts? A room of one’s own? An encouraging mental space? On the page itself? Something else entirely?

RD: We need all of it. We need the public spheres; we need the sorts of friends who quicken us, who delight and amuse and touch us, who disrupt us, whose conversation empowers us; friends with whom to share waking dreams. Friends with whom we may dare be outrageous, ridiculous. Friends we need to walk away from, too. We need the cinema, the stage; we need to be shaken to the core by ideas, by beauty unlike anything we have known before; we need  the silence and safety of our own rooms; we need the museums and we need the wilds. We need the wilds alive with the others, the creatures who are vanishing. Because they are imbedded within us, not only our memories and our dreams, but our very blood and bones and marrow. We have shared an impossibly long and complex voyage together, and as those many respirations are snuffed out, we are ourselves overcome with losses. We are about to find ourselves terribly alone with one another and we cannot bear it. The only animals left will be the ones who have been bred to be our food or our companions, and the neurotic few who pace the world’s many cages. In other words, we need not only our own book, but the world’s book. What will we have to say to one another once all the others are gone?

the silence and safety of our own rooms; we need the museums and we need the wilds. We need the wilds alive with the others, the creatures who are vanishing. Because they are imbedded within us, not only our memories and our dreams, but our very blood and bones and marrow. We have shared an impossibly long and complex voyage together, and as those many respirations are snuffed out, we are ourselves overcome with losses. We are about to find ourselves terribly alone with one another and we cannot bear it. The only animals left will be the ones who have been bred to be our food or our companions, and the neurotic few who pace the world’s many cages. In other words, we need not only our own book, but the world’s book. What will we have to say to one another once all the others are gone?

CC: What I believe to be one of the main driving forces of The Deep Zoo, is this concept of how the core of our humanity can be seen through art. The artwork included in your collection is not just complimentary to your writing, but I would say vital to the book as a whole. If art is where we become visible, and thus able to discover our “unknowns,” what aspects of our core do you think are discovered when text and image intersect?

RD: We come into the world wired to make art. The creative imagination is what drives us, nourishes us, gives us the taste and the capacity for life. The life breath is all about picture making, storytelling, singing, moving the body in experimental ways. All we need to do is watch our children! When I interviewed Linda Okazaki, she revealed the nightmare that fractured her childhood, but also the “powers,” the memories and beauties that never ceased to nourish her. Her paintings, informed by her dreams, are very strange and very beautiful; they are compelling. We do not need to know her story to be taken by them. But her story gives us vital keys to a greater understanding. For example, the animals she paints have a totemic significance; water is an expression of her own private mythic world. As Linda spoke, memories surfaced that she had forgotten or pushed away. So that her work was, in fact, informing both of us with new knowledge. She created new paintings in response to this.

RD: We come into the world wired to make art. The creative imagination is what drives us, nourishes us, gives us the taste and the capacity for life. The life breath is all about picture making, storytelling, singing, moving the body in experimental ways. All we need to do is watch our children! When I interviewed Linda Okazaki, she revealed the nightmare that fractured her childhood, but also the “powers,” the memories and beauties that never ceased to nourish her. Her paintings, informed by her dreams, are very strange and very beautiful; they are compelling. We do not need to know her story to be taken by them. But her story gives us vital keys to a greater understanding. For example, the animals she paints have a totemic significance; water is an expression of her own private mythic world. As Linda spoke, memories surfaced that she had forgotten or pushed away. So that her work was, in fact, informing both of us with new knowledge. She created new paintings in response to this.

I find when I am writing I am often thinking cinematically. And that when I am painting, the ongoing reverie in my mind informs the process, and that the process informs the reverie, but all this is somehow ineffable. It remains mysterious. My texts and my paintings are always all about revelation. I have no interest in repeating myself. I don’t want to know where it is I am going. If I could speak to Eros I’d say: “Hey! Take me somewhere new!” I want to astonish myself and I want to push on further into the wild.

CC: Nature is a reoccurring theme throughout The Deep Zoo. What types of connections between nature and text do you see as contributing to our core of humanity?

RD: In The Deep Zoo, I talk about the early Egyptian glyphs that contained a small world. The glyph itself had a sacred significance and a sacred power. To say the name of a plant, say, was thought to activate the plant’s medicinal benefit and awaken the sacred breath held within it. And the glyph contained medicinal information, too, as well as the name of the god who dwelled there. All that! Language was born of and in nature, and everything communicates!  Did you know that birds and whales have family names? And plants warn one another of predators? In the wild everything is communicating, reverberating; the world is alive with stories. The question is why all this is being betrayed, and irretrievably. It is interesting that the most repressive among us fear the bodies of wolves as much as they fear their own bodies, fear the wild as much as they fear the stranger. The most repressed and repressive people I know fear politics as much as they fear poetry, fear life as much as they fear death. There is a gnostic terror of the body in our culture and it is not serving us well.

Did you know that birds and whales have family names? And plants warn one another of predators? In the wild everything is communicating, reverberating; the world is alive with stories. The question is why all this is being betrayed, and irretrievably. It is interesting that the most repressive among us fear the bodies of wolves as much as they fear their own bodies, fear the wild as much as they fear the stranger. The most repressed and repressive people I know fear politics as much as they fear poetry, fear life as much as they fear death. There is a gnostic terror of the body in our culture and it is not serving us well.

CC: The Deep Zoo is a very intelligent and engaging collection of essays. I would imagine you did a lot of research and reading in preparation for writing these pieces. In the context of your researching and writing process, what are some of the successes, challenges and/or surprises you experienced?

RD: The essays had a way of leading me into places I could not imagine. How marvelous to learn that the male monarch seduces his mate with fragrance! That the Marquis de Sade found one of his own books to be so unsettling he could not, himself, read it! That Cortazar learned of his own mortality as an infant in his crib when he heard the crowing of a cock! That virtual reality is about to transform our culture, utterly!

CC: What are you working on now?

RD: In a few years Bloomsbury Books in London is bringing out a three-volume encyclopedia of Surrealism, from its beginnings to the present. I just learned I am included among the many wonderful artists and writers who have been engaged in the Surrealist adventure, and I have been asked to write several essays for the volume devoted to subjects of particular significance to Surrealism: the Marquis de Sade, the Imagination, Gnosticism and Metamorphosis.

CC: Is there anything else you would like readers to know?

RD: Writing is exhilarating, demanding and lonely. But writers and readers are of the same tribe; we inform one another, we enter into a deep reverie together, we share a particularly exciting place in the wild wood, that place of far seeing and aesthetic adventure, of the unbridled imagination, of knowledge and transformation, of clairvoyance and delight! For me the journey into a book is no longer lonely because I know my tribe is there, has taken me in and I am really grateful.

The Deep Zoo is a part of the Eckleburg Book Club. Check it out HERE.

The author of nine novels, three collections of short fiction, two books of essays and five books of poetry, Rikki Ducornet has received both a Lannan Literary Fellowship and the Lannan Literary Award For Fiction. She has received the Bard College Arts and Letters award and, in 2008, an Academy Award in Literature. Her work is widely published abroad. Recent exhibitions of her paintings include the solo show Desirous at the Pierre Menard Gallery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 2007, and the group shows: O Reverso Do Olhar in Coimbra, Portugal, in 2008, and El Umbral Secreto at the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende in Santiago, Chile, in 2009. She has illustrated books by Jorge Luis Borges, Robert Coover, Forest Gander, Kate Bernheimer, Joanna Howard and Anne Waldman among others. Her collected papers including prints and drawings are in the permanent collection of the Ohio State University Rare Books and Manuscripts Library. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, Santiago Chile, The McMaster University Museum, Ontario, Canada, and The Biblioteque Nationale, Paris.

Chelsey Clammer has been published in The Rumpus, Essay Daily, The Water~Stone Review and Black Warrior Review (forthcoming) among many others. She is the Managing Editor and Nonfiction Editor for The Doctor T.J. Eckleburg Review. Clammer is also the Nonfiction Editor for Pithead Chapel and Associate Essays Editor for The Nervous Breakdown. Her first collection of essays, BodyHome, is forthcoming from Hopewell Publishing in Spring 2015. Her second collection of essays, There Is Nothing Else to See Here, is forthcoming from The Lit Pub, Summer 2015. You can read more of her writing at: www.chelseyclammer.com.

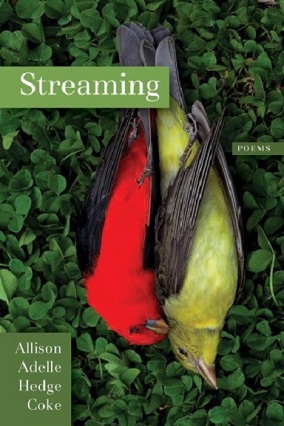

We are within the atmosphere of the world, always. Unless we venture beyond, and then what happens? We look back to it to understand the body of the world we call home from the universe, or multiverses, beyond this portion. We are like the minute cells, and the world is like the larger organism that is in the increasing and ever expanding space we exist within. Where does that take us? Back to the cells we work with, then their interaction with everything else – our own sensory devices, sensual awareness.

We are within the atmosphere of the world, always. Unless we venture beyond, and then what happens? We look back to it to understand the body of the world we call home from the universe, or multiverses, beyond this portion. We are like the minute cells, and the world is like the larger organism that is in the increasing and ever expanding space we exist within. Where does that take us? Back to the cells we work with, then their interaction with everything else – our own sensory devices, sensual awareness. And how is time something more than what leads us and marks our experiences? How we engage with time and with our familiarity of its ebb and flow, of its peculiarities, perhaps motivates us to seek to define its parameters and push them or to find some sense of comfort without our perception of it, right or wrong. Understanding the wrinkles, echoes, the motion of it, might give us the ability to more deeply conceive of how prophesy, how intuitiveness, how hunches work, or what gives nature its meaningfulness, for that matter. If, as my dad told us as children, we manage to do something phenomenal in this very moment, the impact of that is so great it courses throughout the fabric of time. That impression could then cause the idea to present in someone receptive on either side of the temporal flow. Insomuch a dream, a thought, a notion, a story, a moment of brilliance could then enlighten, so the person behind us (in time) who perhaps now receives a bit of clarity on what is to come, before it happens, in their time, while we impress away in ours, and on so. In our movement in time, our choices, our strategies, our approaches give us, perhaps, some malleable platforms with which to do significant work, if we choose to. I think that the closer we are, and the more comfortable we are with nature, and with our own natures, the closer we may come to delivering those possibilities as they present and are presented to us. I hope to seize some of the opportunity in the days and nights I meet and in the poetry and work that I commit to. In Streaming, I hope to build on those relationships and present some of the features of physics of these junctures and of our movement through them.

And how is time something more than what leads us and marks our experiences? How we engage with time and with our familiarity of its ebb and flow, of its peculiarities, perhaps motivates us to seek to define its parameters and push them or to find some sense of comfort without our perception of it, right or wrong. Understanding the wrinkles, echoes, the motion of it, might give us the ability to more deeply conceive of how prophesy, how intuitiveness, how hunches work, or what gives nature its meaningfulness, for that matter. If, as my dad told us as children, we manage to do something phenomenal in this very moment, the impact of that is so great it courses throughout the fabric of time. That impression could then cause the idea to present in someone receptive on either side of the temporal flow. Insomuch a dream, a thought, a notion, a story, a moment of brilliance could then enlighten, so the person behind us (in time) who perhaps now receives a bit of clarity on what is to come, before it happens, in their time, while we impress away in ours, and on so. In our movement in time, our choices, our strategies, our approaches give us, perhaps, some malleable platforms with which to do significant work, if we choose to. I think that the closer we are, and the more comfortable we are with nature, and with our own natures, the closer we may come to delivering those possibilities as they present and are presented to us. I hope to seize some of the opportunity in the days and nights I meet and in the poetry and work that I commit to. In Streaming, I hope to build on those relationships and present some of the features of physics of these junctures and of our movement through them.

AAHC: More poems, more songs, new stories, old memories, a film – In this exact moment, I am preparing for wherever I can do the best work and make use of myself, whatever that is. The most I want of life is to be useful within it and not so much of a drain upon it.

AAHC: More poems, more songs, new stories, old memories, a film – In this exact moment, I am preparing for wherever I can do the best work and make use of myself, whatever that is. The most I want of life is to be useful within it and not so much of a drain upon it.

BZ: The setting was a very deliberate choice. And it’s a real place, more or less. I’ve always been attracted to John Ruskin’s idea of the pathetic fallacy, and if misery truly loves company than I think it stands to reason that somebody who feels desolate and fouled will seek out a landscape or an environment that mirrors what they’re feeling. It’s obviously not healthy, but I can attest from personal experience that it happens. The area around that refinery south of the Twin Cities—particularly in the dead of winter—is about as inhospitable a place as you can imagine. I’d spent a good deal of time poking around there, and when I was writing House of Coates it just seemed like the natural place to do it. I had no plans initially to set the story there; I was just looking for a suitable spot to hole up and work without distraction. But once I was hunkered down in a little strip motel up the highway from the refinery—and this was in the middle of a particularly dreadful Minnesota winter—the environment became a major distraction and a central part of the experience, and I started seeing Lesters everywhere.

BZ: The setting was a very deliberate choice. And it’s a real place, more or less. I’ve always been attracted to John Ruskin’s idea of the pathetic fallacy, and if misery truly loves company than I think it stands to reason that somebody who feels desolate and fouled will seek out a landscape or an environment that mirrors what they’re feeling. It’s obviously not healthy, but I can attest from personal experience that it happens. The area around that refinery south of the Twin Cities—particularly in the dead of winter—is about as inhospitable a place as you can imagine. I’d spent a good deal of time poking around there, and when I was writing House of Coates it just seemed like the natural place to do it. I had no plans initially to set the story there; I was just looking for a suitable spot to hole up and work without distraction. But once I was hunkered down in a little strip motel up the highway from the refinery—and this was in the middle of a particularly dreadful Minnesota winter—the environment became a major distraction and a central part of the experience, and I started seeing Lesters everywhere. CC: I want to provide some examples of how the language, pace and structure of each sentence in the novel is, well, astounding.

CC: I want to provide some examples of how the language, pace and structure of each sentence in the novel is, well, astounding.