It was one of the most shameful moments of my life. It is one that I will never forget and from which I will never recover.

***

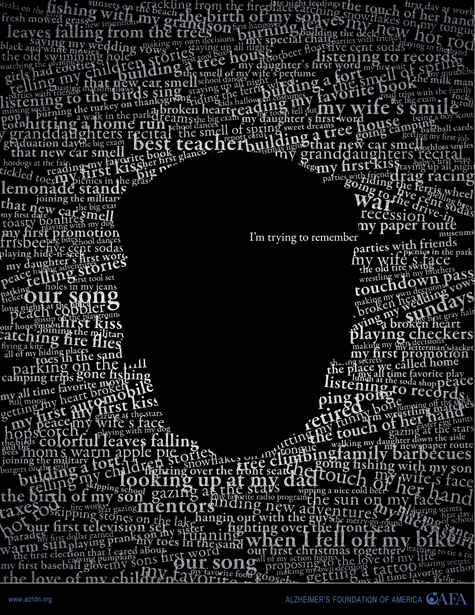

For years, my father had been showing the signs of Alzheimer’s disease. The once brilliant mind and sharp wit had dimmed a bit, and it was getting harder and harder for him to keep things straight. Conversations with my father had always been powerful for me. He had the ability to follow my ramblings, ask probing questions with genuine interest, and give feedback or commentary that often made me think further on a certain issue. He was this way with most people, especially my friends, and we had a running joke that my friends had better not start a conversation with my dad unless they had plenty of time on their hands. But his ability to carry on such dialogue had become curtailed, and his short answers, or even silence, stood in great contrast to the talker most people knew. One Christmas, I gave him the gift of an outing each month—just the two of us—to a place of interest for the day. Our car rides, which had previously been packed with storytelling or ponderings about life, instead became filled with wordless spaces and repeated information from previous conversations. His disease was advancing.

It was about six years after my parents became aware of my father’s likely diagnosis of Alzheimer’s when they decided to move to Georgia to be closer to where my sister and I live. When they first learned of his disease, they had discussed what was likely to happen and decided to just handle whatever came their way. But after those years of slowly taking charge of his affairs—first the checkbook and the bills and then daily dressing and shaving—and months of calming his nightly hallucinations and heading off his neighborhood wanderings, my mother became exhausted. Unable to physically and emotionally handle the stress, and at seventy-five, no youngster herself, my mother decided she needed for him to live in a place where constant vigilance would be possible.

We must have toured half a dozen places within a thirty-mile radius. All lookedthe same, with long rivers of green carpet punctuated by maroon chairs and gilded lamps. All gave the same pitch: bingo, chair exercises, sharing time, and music and art classes. I wanted very badly to believe that my father could still engage in these activities and enjoy these activities. My mother, ever the optimist, talked up these features to him and emphasized all of the interesting ways he could engage with people in a new setting. Looking back, I don’t think my father actually understood that each of the places he toured was a potential new home for him, but he nodded politely and looked around.

Not until we actually moved my father into his place did I realize that for those on the “memory care” wing, such activities were a pipe dream, as they were unable to follow along. The facility, about a thirty-minute drive for me and for my mother, was fairly typical in having different stages of care, with a passcode-controlled elevator to the memory care unit. Both staff and family members knew the code but not the residents.

I don’t know how we ever got my father to agree to move in. On some level, he must have known how hard it was for my mother and could tell from her demeanor that it was something she really wanted. After more than forty years of marriage, he could likely still read her needs and characteristically followed her lead. Yet when we moved him in, he really didn’t know what he was doing there or why we had to leave without him.

My father was a smart guy, and he was curious about the world around him. He was a great listener, a practical joker, a writer, a World War II veteran, and, at times, a mind reader. He lived a full life that was in some ways selfish and in others incredibly giving. He’d hand-fed his own mother for months after she’d had a stroke, which took hours. And he was wickedly funny. The kind of funny where you laughed when you knew you shouldn’t. The kind of funny my mother called “bathroom humor” but that we kids just couldn’t help but try to emulate. So how was a smart and very funny guy—one who knew that he lived in a house with his wife and not in this room that people keep wandering into—ever going to get used to his new surroundings? Well, he wasn’t. But he took it with good manners that day.

My mother was the first to leave. I think she, after decades of being a mother, did what she always did with firsts: dropping him off in his new surroundings and telling herself that he would adapt. My sister and I stayed for a while, but with little to say, and knowing my father had to get used to his new place, we had to leave, too. I don’t know how it was for him those first few nights since I wasn’t there. Because of work, I didn’t go back for several days. When I did, I realized that there would be no getting used to his new surroundings. It would never feel like home, and the place was a prickly reminder that my father was forever unwell.

***

One day, a few months after we’d settled him into the facility, I left work in the afternoon and made the half-hour drive to his facility.

I arrived toward the end of the lunch hour and sat with him, watching him ever so slowly devour his favorite food—strawberry ice cream. That man loved his strawberry ice cream. He wouldn’t be rushed. And with his new set of dentures floating in his mouth, he couldn’t be rushed.

I tried to make conversation with the other residents sitting at my father’s table but soon realized that my father was one of the higher functioning persons there. He could still hold a conversation, albeit one that could have taken place decades earlier. For the most part, he knew I was his daughter, though he sometimes got me confused with other people. Once, he was convinced that he needed to leave to be in court. In retirement, he had volunteered as a court-appointed special advocate for children who had been abused, and he often had to attend hearings. I tried the reality tactic, which mostly doesn’t work with people with Alzheimer’s. And then told him it was Saturday, that court wouldn’t be in session over the weekend, which calmed him down.

But on this day, he knew it was his daughter visiting, and he was pleased to be eating his strawberry ice cream. After he finished, we took a stroll around the floor, and I took his lead in the conversation. I don’t remember what we talked about, though I know he didn’t talk much. He must have thought it was just another day like any other, and we were just hanging out together.Everything was fine until it came time for me to leave. I had to get back to work.

So I said my goodbyes to my father, punched in that code, and steered him away from the elevator as I didn’t want him to see me go. But my father, being the smart man he was, and not at all being used to his environment, steered himself right back to me, fully intending to get on that elevator with me. As I stood there, I saw him coming toward me, upset and confused. He just wanted to go with me, back to the life he had and the family he loved. And I let the elevator door close.

I’ll never forget the look on his face, and the shame and betrayal I felt at letting that door close. I went out to my car and sobbed for a long time, horrified at what I’d just done, but I knew that I wasn’t going to get back the father of my memory, the one who could have left with me. I cried and cried and apologized. I mourned the man I had lost and the daughter I had become.

***

There were several shocking and arguably worse experiences in the months that followed before he died. There were things I saw and felt that turned my world upside down, filled me with panic that I could not escape, and made me cry until my eyes were sore. But nothing could compare to what he must have gone through—a brilliant man stuck in a decaying mind and terrifying end to a wonderful life. In the decade that has passed, I’m not pained less by those experiences or by losing my father this way. But it has changed the way I interact with people who are aging, gradually losing the things we all take for granted. I like to think it has helped me be a bit more patient, a little more appreciative, and aware that my time, too, will come.