Zora Neale Hurston’s novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, is a masterful texturizing in the sins, virtues, venalities and advantages of living. The characters and landscapes present vehicles for presenting these tiny sins and virtues on the canvas so that the reader can experience it all with a sort of clarity and contrast within each scene, a chiaroscuro. How does your narrative use voice and texture to create chiaroscuro?

Reading & Viewing

- Chiaroscuro and Texture in Their Eyes Were Watching God (Excerpt). The Eckleburg Workshops.

- Their Eyes Were Watching God (Novel). Zora Neale Hurston.

- Their Eyes Were Watching God (Film). Darnell Martin.

Discussion

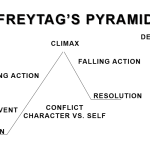

Below, in the discussion area, describe how chiaroscuro and texture are important. Use the below arc examples as you consider texture and chiaroscuro within your scene.

| Character Arc | Structural (Plot) Arc | Textural Arc |

|

|

|

|

Conflict Character vs. Self *If you have not yet read Their Eyes Were Watching God I’m strongly encouraging you to read it now. See links above. Story is built on conflict. As literary writers, we most often begin with the essence of our most intriguing character and that character’s primary internal conflict. Begin with a focus on character and internal conflict when drafting a first version of a short story, novel or even a single scene. In Their Eyes Were Watching God, we meet Janie as she returns home from burying her lover, after running off from her “proper” life. She is broken and vulnerable and her neighbors and friends in Eatonville assume Janie’s lover, Tea Cake, has “done her wrong.” |

Conflict Character vs. Character vs. Nature vs. Society vs. Supernatural Janie battles not only the gender position of being female in Eatonville and a man’s world and a “white” run world but also the position of being human in a hurricane and “under God.” It seems that all the conventions are against her. She is an innocent, smart, strong, beautiful and capable character and we have the privilege of being with her as she takes her journey through multiple external conflicts. How does Janie, in some way, regardless of gender, ethnicity, community… embody something of you as the reader? |

Conflict Imagery vs. Character vs. Place Symbolism vs. Character vs. Place Repetition vs. Character vs. Place Time plays an important motif in the novel. We repeatedly return to Janie’s age and the repetition of returning home and how individuals, like water, can move out with the tide and come back to land again. Water also presents as a motif in the different forms it can take: the sea and the freshwater as in a lake or pond in which Janie communes with her organic self. She not only moves out with the sea tide—leaves home, leaves Eatonville—she also communes with her “still self” when she wades and floats in the still freshwater. The repetition of age and water within the narrative creates a texture of human passage. Do we not all experience Janie’s movements within tides and stillness in our own ways? |

Writing Exercise

Choose a scene from one of your existing works—novel, short story or short short story—and explore it within the above arcs and examples. As you rewrite this scene, focus on how conflict feeds the characters, iconic items and more.

Submit for Individualized Feedback

Please use Universal Manuscript Guidelines when submitting: .doc or .docx, double spacing, 10-12 pt font, Times New Roman, 1 inch margins, first page header with contact information, section breaks “***” or “#.”

Sources

A Handbook to Literature. William Harmon.

The Norton Anthology of World Literature: Literary Terms. Martin Puchner, et al.

Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft. Janet Burroway, Elizabeth Stuckey-French & Ned Stuckey-French.

Their Eyes Were Watching God. Zora Neale Hurston.