Lesson No. 1: Narrative Short Poems with John Sibley Williams

Welcome! After providing a few overall tips for creating short poems, we will focus this lesson on writing short narrative poetry about a personal experience in a way that resonates with readers and echoes off the page. We will study works by Pauline Petersen, William Stafford, Zubair Ahmed, and more.

Tips on Writing Short Poems

| 1) Choose a title that provides context for the poem, be it the overarching metaphor or a significant detail/image. | |

|

|

| 3) Cull extraneous words, unfocused images, and extended monologue. | |

| 4) Ensure your first and last lines are powerful, as they respectively introduce readers to your world and define the poem’s lasting impression. | |

| 5) Consider carefully each line and stanza break, as well as the placement and usage of punctuation | |

| 6) Ensure each image and detail doubles as both metaphor and grounded anchor, eliminating those that don’t serve a grander purpose. | |

| 7) Keep a consistent tone, mood, and voice throughout. | |

| 8) Never stray far from the poem’s core metaphor. | |

| 9) Avoid over-explaining, allowing readers to come to their own conclusions instead. | |

| 10) Consider the use of intuitive and imaginative (sometimes even surreal) leaps in the poem’s narrative. Trust the reader to make those leaps with you. |

As there is no better way to discuss poetry than to dissect successful poems and see what tools the poet applied, here are three pieces that approach the narrative short poem from distinct angles. Following each poem is a set of notes that highlight the poet’s tools, techniques, and approaches. Please read each poem at least twice before reviewing the notes. After reading Petersen and Stafford’s works, try taking your own notes on Ahmed’s poem.

After studying the above tips and below annotated poems, you will find your reading, discussion, and writing assignments. Each week I will include a mix of essays and further poem examples for your review, and you will be asked to write a minimum of one new poem inspired by the reading.

Annotated Example #1

Paulann Petersen

Feeding Crows

I can move closer. Too much

and they scatter. Snap and clatter of black

lifted to trees. Caw and creech railing at intrusion.

Of late, my heart startles, flying against my chest.

Aberrant beats, thousands each day. Panicked,

I tell it, I must tame you to survive.

No. I’ll give this dark nester

what it craves. Sleep

laden with dreams. Then—from a distance—

morsels of fond neglect.

Notes on poem. Notice:

- The title, which provides context for the poem and frees Petersen to not have to reference birds again. She can be more flexible and abstract because she has already anchored us with a tangible, grounded image.

- Petersen’s very specific, surprising, and unique word choice.

- Her verbs are contextually accurate, evocative, and repeat similar consonant and vowel sounds, creating flow and cohesion (scatter, snap, caw, creech, crave, tame).

- Few adjectives, but those she uses provide mood (black, dark, aberrant).

- No extraneous words or tangents; very focused language.

- The first and last lines.

- “I can move closer” provides ambiguity and mystery, pulling the reader in.

- “Then—from a distance—/ morsels of fond neglect” leaves the reader asking questions with a powerful combination of words.

- How Petersen’s use of punctuation molds how we read the poem.

- Short lines are hard-stopped on periods.

- Commas provide a breathy pause and em dashes a physical distance that enhances the metaphorical distance she describes.

- How Petersen never strays from her core image. Every word is tightly wound around a single experience, which she uses as a metaphor about her own nature.

Annotated Example #2

William Stafford

Across Kansas

My family slept those level miles

but like a bell rung deep till dawn

I drove down an aisle of sound,

nothing real but in the bell,

past the town where I was born.

Once you cross a land like that

you own your face more: what the light

struck told a self; every rock

denied all the rest of the world.

We stopped at Sharon Springs and ate—

My state still dark, my dream too long to tell.

Notes on poem. Notice:

- How the title gives all the specifics the reader requires. We all know of Kansas’ flatness, its barren fields, its sense of loneliness, yet it’s also part of the ‘heartland’. He says Kansas, and we immediately have a picture in our minds. That one word does a lot of work in the poem.

- How Stafford speaks directly to the reader in the second stanza. This tactic creates immediacy and makes the reader personally invested in the poetic outcome.

- Stafford’s line breaks. Apart from “that”, each line ends with a strong, evocative noun or verb that drives us into the following line. Notice also how each line begins with incredible verbs (struck, denied) and perspective-shifting pronouns (I, you, and we).

- How Stafford balances specifics with universal imagery.

- He uses common nouns (bell, sound, town, land, rock, world) that can resonate with any reader while also giving us a specific location and characters (his family).

- His tactics in moving at ease between the intimate and the conceptual.

- He speaks to his inner world with the first person pronoun, utilizes the second person “you” to directly include the reader in the poem, and then moves back to the intimate “I” to conclude the poem on a personal note.

- His last line pans out from firsthand experience so we feel the full weight of his metaphor. Also, the word “state” could signify Kansas or his mental state, which leaves the poem on a wonderfully ambiguous question.

Annotated Example #3

Zubair Ahmed

A Field of Wells

My great-grandmother left

Before the sun rose

To gather water from a field of wells

Seventeen miles north.

I watched from my bed

As she kneeled in the corner

And bathed her arms with dust.

I think she prayed.

She opened the door,

Careful not to waken the crickets

Sleeping within us.

Before she left, her face forgot

Our names.

Today, the Ganges will be dense

With dead bodies.

Notes on poem. Notice:

- How Ahmed shows so much more than he tells. His meanings are implied, not stated, which allows the reader to interact with the poem on his or her own personal terms.

- How fluidly the poem moves from the extremely intimate to the universal (from the author’s great grandmother to an entire culture’s worth of casualties) until ultimately they blend and become one single poetic thread.

- Ahmed’s careful selection of details. In keeping each image anchored yet broad, he invites the reader into the poem and into the lives of the character and narrator. His great grandmother is our great grandmother. His Bangladesh is our own country.

- How the poem holds us tight to its breast until the final two lines, when it opens up to the larger world and broader historic context. Suddenly what seemed like a family narrative becomes a cultural narrative.

- The consistently mysterious tone. From the highly metaphorical title to the haunting closing image, each line has an ephemeral quality that seems fitting for a poem about loss and grief and family.

Readings: Narrative Short Poems

“Some Notes on Organic Form”, by Denise Levertov (essay; 3 pp.)

“Approximately Forever”, by C. D. Wright (poem)

“Afterlife”, by Bruce Snider (poem)

“The Resurrection of the Body”, by Eric Pankey (poem)

Discussion

After reading Levertov’s article, use the comment forum below to provide a quote from the article that piqued your interest. You can agree with it, disagree with it, or simply wish to delve deeper into it.

Writing Exercise

With Stafford, Ahmed, and Petersen’s poems in mind, please construct a metaphorical poem based on an experience or memory.

Steps

1) Take a moment to consider a specific experience from your life, one that could potentially resonate with others and that speaks to something you consider important.

2) List a few details about this experience: the who, what, where, when, how, but in particular the why, as in: why does this experience matter?

1. Mark or highlight those you think are particularly interesting and evocative.

2. What poetic images might you be able to construct from these details?

3) Consider what mood would you like to create. How do you want the reader to feel: heart-broken, joyous, contemplative?

4) Consider what you want to say in this poem. What meaning might you want it to convey to others?

5) Now, begin to write. Start powerfully, perhaps with a stark image.

John Sibley Williams’ writing has appeared in American Literary Review, Third Coast, and RHINO. He is the author of eight poetry collections, most recently Controlled Hallucinations (FutureCycle Press, 2013). Four-time Pushcart nominee, he is the winner of the HEART Poetry Award and has been a finalist for the Rumi, Third Coast, Ian MacMillan, Best of the Net, and The Pinch Poetry Prizes. John serves as editor of The Inflectionist Review and Board Member of the Friends of William Stafford. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Rivier College and an MA in Book Publishing from Portland State University, and he currently works as Marketing Director of Inkwater Press and as a literary agent. John lives in Portland, Oregon.

John Sibley Williams’ writing has appeared in American Literary Review, Third Coast, and RHINO. He is the author of eight poetry collections, most recently Controlled Hallucinations (FutureCycle Press, 2013). Four-time Pushcart nominee, he is the winner of the HEART Poetry Award and has been a finalist for the Rumi, Third Coast, Ian MacMillan, Best of the Net, and The Pinch Poetry Prizes. John serves as editor of The Inflectionist Review and Board Member of the Friends of William Stafford. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Rivier College and an MA in Book Publishing from Portland State University, and he currently works as Marketing Director of Inkwater Press and as a literary agent. John lives in Portland, Oregon.

WEEK ONE: Using Optical Illusions to Form Narrative in Magic Realism

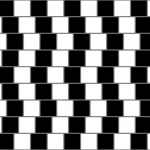

In the above optical illusions, notice how your mind can be so certain of its perception and then your mind can shift just as certainly to another perception. The lines are offset. No, they are parallel. It’s a wine glass. No, it’s a picture of twin profiles. It’s a head shot of a man with part of his face erased. No, it’s a side profile of a man. Optical illusions engage the viewer in a way that forces creative problem solving.

It is difficult to hold two diverse perceptions at one time, though, not impossible; however, to hold two diverse perceptions requires a sort of blurring of perceptions. Neither of the individual perceptions can be held with great clarity and focus if both are simultaneous and so we accept one perception at a time as our focus and understand that another perception is equally valid. This blurring of realities, this acceptance of alternative perceptions, is the essence of magic realism.

In The Age of Insight, Eric Kandel discusses the “beholder’s share” or what the reader brings to the experience of reading our works. We are not going to read The Age of Insight in this lesson, it is a tome, but we will be using some of Kandel’s above optical illusion examples as well as his explorations into the science of perception.

In Kandel’s explorations, he discusses how illusion can affect the nuance and understanding of an element in a story, article, painting or drawing, changing the interpretation as the element relates to its background. If we relate this to narrative, this illusionary aspect creates a secondary setting, one that is not physical, but rather contextual and relational to the background within any given scene. This background can change in the reader’s perception, even though the elements of the background may not have changed at all. The “beholder’s share.” We’re going to use this concept in our writing in order to create a richer, deeper story while incorporating elements of magic realism.

First, let’s review the basics of magic realism and how it fits and sometimes doesn’t fit into the spectrum of genre and style.